A Higher Purpose:

Newcastle University at War

Find out how the First World War impacted on the University 100 years on through using original photographs and documents from the University Archives...

A Work in Progress:

Newcastle University up to 1914

Newcastle University evolved from two nineteenth century educational establishments: the College of Medicine (1834) and the College of Science (1871).

After starting life through lectures given at the Barber Surgeons’ Company Hall in the Manors, the College of Medicine eventually found a permanent home in Orchard Street (below) in 1852, coinciding with formal recognition of the qualifications it awarded.

Illustration of the College of Medicine on Orchard Street, c. 1852

Illustration of the College of Medicine on Orchard Street, c. 1852

The College of Science was initially housed in a number of rooms rented from, amongst others, the College of Medicine itself. Following the expansion of the railways, which served both colleges a notice to quit their premises in 1884, the College of Medicine relocated to Northumberland Road, where it enjoyed one of the most up to date premises in the country. This is now Northumbria University’s Sutherland Building.

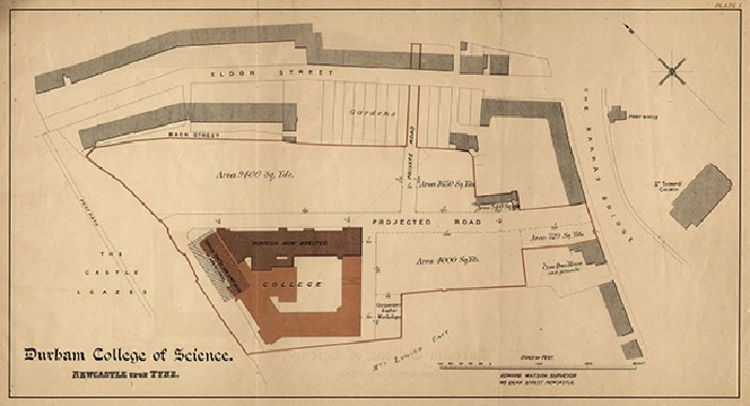

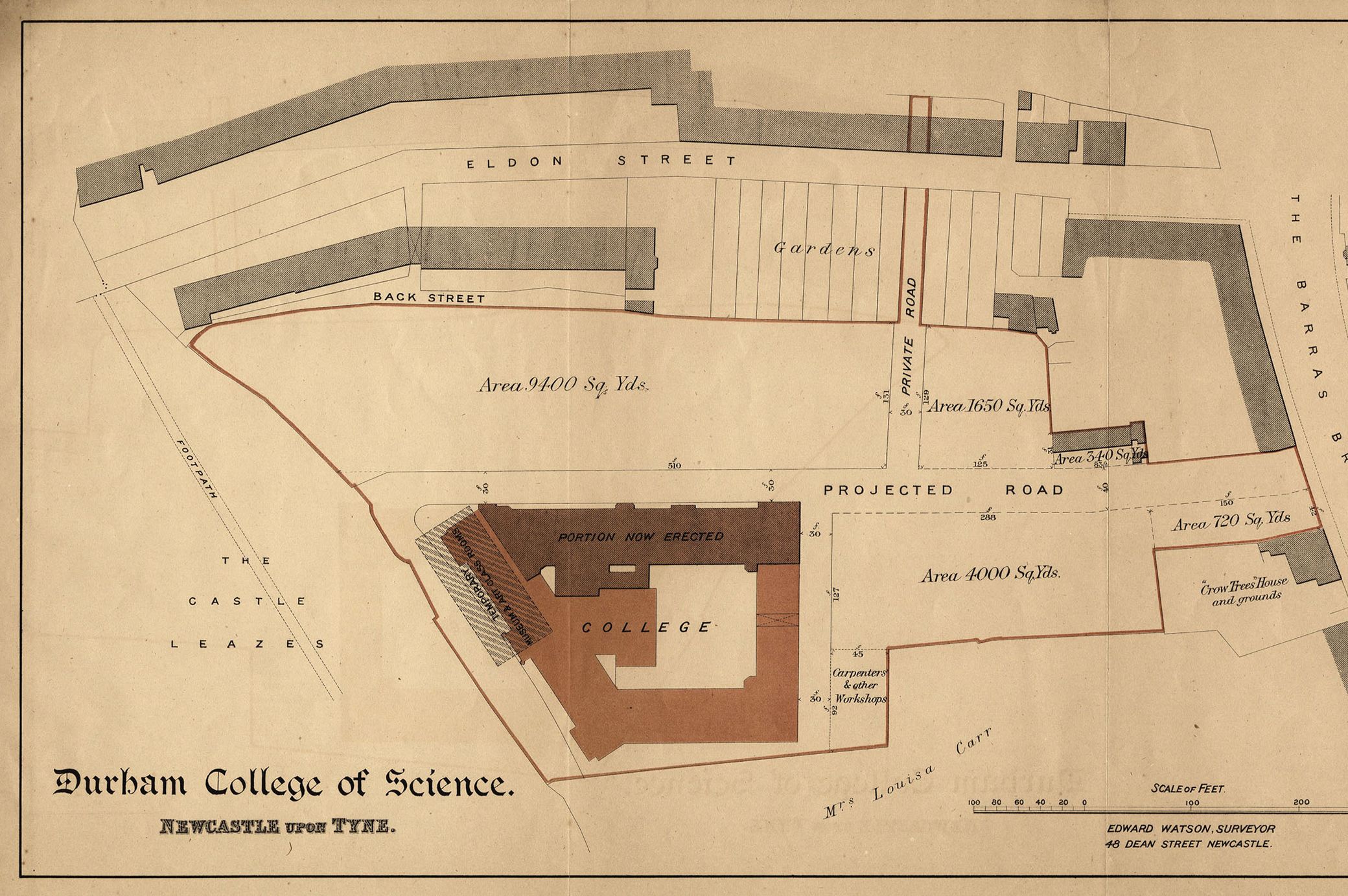

It took some time for a suitable location for the College of Science to be found, but in 1886, land for a new college building was purchased on the site of Lax’s Gardens, thus named because it was formerly in the possession of a Mrs Lax.

Construction of the new College of Science began in 1887 and progressed in stages until finally completed in 1904 and officially opened by King Edward VII in 1906.

Plan of Durham College of Science (c. 1888-1891)

Plan of Durham College of Science (c. 1888-1891)

The above image of the site plan appears to have been created between 1888 and 1891. The phase 1 building of the Armstrong Building has been completed and a location drawn on for the remainder of the building work. We know from this and other plans that all 3 phases were planned before any construction took place.

The drawing also shows the extent of the land owned by the college, shown in a red line. It may have been drafted soon after the completion of phase 1 for the purpose of record keeping, but also as a propaganda tool. It is quite decorative for a simple survey, serving as an illustration for the college to show the potential for new buildings.

At this time it was very difficult to find funding for building work, so the college may not have known how long it would be until they built the next phase.

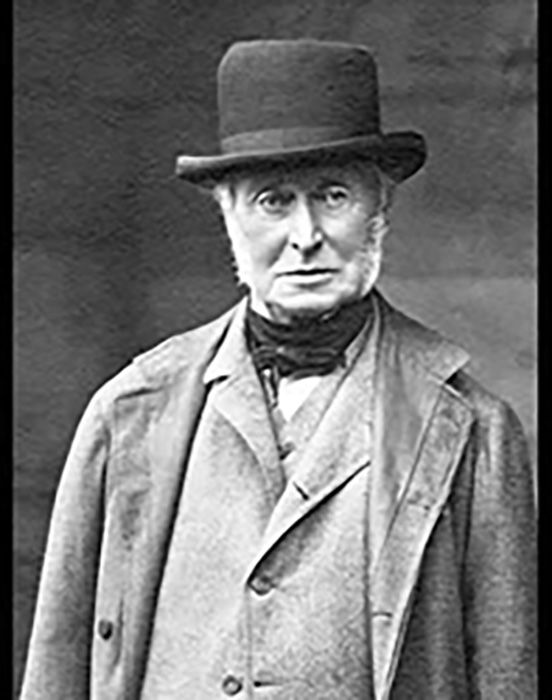

It was decided to name the institution and building ‘Armstrong’ in recognition of the support local scientist and businessman Lord Armstrong gave to the college in its early days.

Photograph of Lord Armstrong

Photograph of Lord Armstrong

The Armstrong Building still exists as the largest building in the University quadrangle facilitating many diverse teaching needs.

Background image: Plan of Durham College of Science (c. 1888-1891)

First Northern General Hospital:

A Tale of 3 Buildings

Before the war, accommodation in military hospitals was approximately 7,000 beds. By the end there was 364,133. Local Government and other municipal bodies, as well as private individuals, were expected to cooperate with the Army Medical Service to install military hospitals in existing buildings. This placed a huge strain on the University on finding buildings to accommodate injured servicemen.

The war effort essentially took over Armstrong College’s 3 major teaching centres in order to function as the greatest part of the First Northern General Hospital for wounded military personnel.

These 3 buildings were:

Armstrong Building

The Armstrong Building was the first and original and built in 3 phases. The final phase, (fronting on to Queen Victoria Road) was opened on 11th July 1906 by King Edward VII.

Photograph of Armstrong College, c. 1906

Photograph of Armstrong College, c. 1906

Armstrong College was one of the institutions requisitioned to house the First Northern General Hospital. While Newcastle wasn’t alone in this respect, with similar Colleges requisitioned in Leeds, Birmingham, Sheffield and London, it meant many buildings could not be used for teaching purposes until October 1919.

Photograph showing 2 of the 4 pavilions erected in 1917 to house additional beds, showing the strain on the university of accommodating some 41,896 servicemen over the course of the war, NUA/041017-24

Photograph showing 2 of the 4 pavilions erected in 1917 to house additional beds, showing the strain on the university of accommodating some 41,896 servicemen over the course of the war, NUA/041017-24

King Edward VII School of Art

The second building (the original part of the Fine Art Building and the “Arches”) was opened in 1911 as the King Edward VII School of Art following a donation of £10,000 from a local mine-owner. This is now part of the Hatton Gallery.

King Edward VII School of Art, the original part of the Fine Art Building and the 'Arches' (now part of the Hatton Gallery), c. 1911

King Edward VII School of Art, the original part of the Fine Art Building and the 'Arches' (now part of the Hatton Gallery), c. 1911

Agriculture Building

Finally in 1914 the Agriculture Building was built (now part of the Architecture Building), through a donation of £5,000 by Dr Clement Stephenson, a local veterinary surgeon. Before the College could occupy this last building, it was requisitioned, meaning it was a hospital before teaching there had even taken place.

Photograph of the Agriculture Building (now part of the Architecture Building), c. 1914

Photograph of the Agriculture Building (now part of the Architecture Building), c. 1914

The 3 photographs shown on the left (scroll down to reveal each one) show the development of the Armstrong Building in becoming a focal point and the oldest building in Newcastle University's quadrangle.

Phase 1...

This phase was designed by local architect Robert J. Johnson in 1886 and constructed between 1887 and 1888. It comprised the north east wing which faces onto the university quadrangle. Johnson described the style as ‘early Jacobean English’, including ornamental gargoyles and Gothic style buttresses. Lord Armstrong laid the foundation stone in 1887 and this can be seen on the façade facing the quadrangle.

The quadrangle itself was paved during the construction of phase 1, further highlighting the College’s intention to expand.

Phase 1 was opened by HRH Princess Louise on 5th November 1889.

Phase 2...

The original architect Robert J. Johnson initiated the design of phase 2 working closely with Frank W. Rich. After Johnson died in 1892, Rich carried out the remaining works up to completion. Phase 2 forms an L. shape comprising the south east and south west wings of the Armstrong Building. The Jubilee Tower sits centrally within the south east elevation and was built to mark Queen Victoria’s Jubilee, using money from the 1887 Town Moor Exhibition. The tower originally signified the main entrance to the College, with the south east elevation forming the primary frontage to the city centre.

Phase 2 opened in 1894.

Phase 3...

This phase consists of the North West wing, which faces Queen Victoria Road and was designed and built between 1903 and 1906. The plans for phase 3 were initially developed by the original architect Robert J. Johnson but completed by W. H. Knowles. The design signaled a distinct shift in architectural style from the Gothic overtones of the first 2 phases and instead embraces Italian classical traditions. The elaborate 3 story frontage onto Queen Victoria Road became the formal entrance defined by the seven story tower which contributes to the building’s prestige. King’s Hall, which became a ward during World War I, was part of these phase 3 works.

On completion of phase 3, King Edward VII officially opened the Armstrong Building on 11th July 1906.

Back to Blighty:

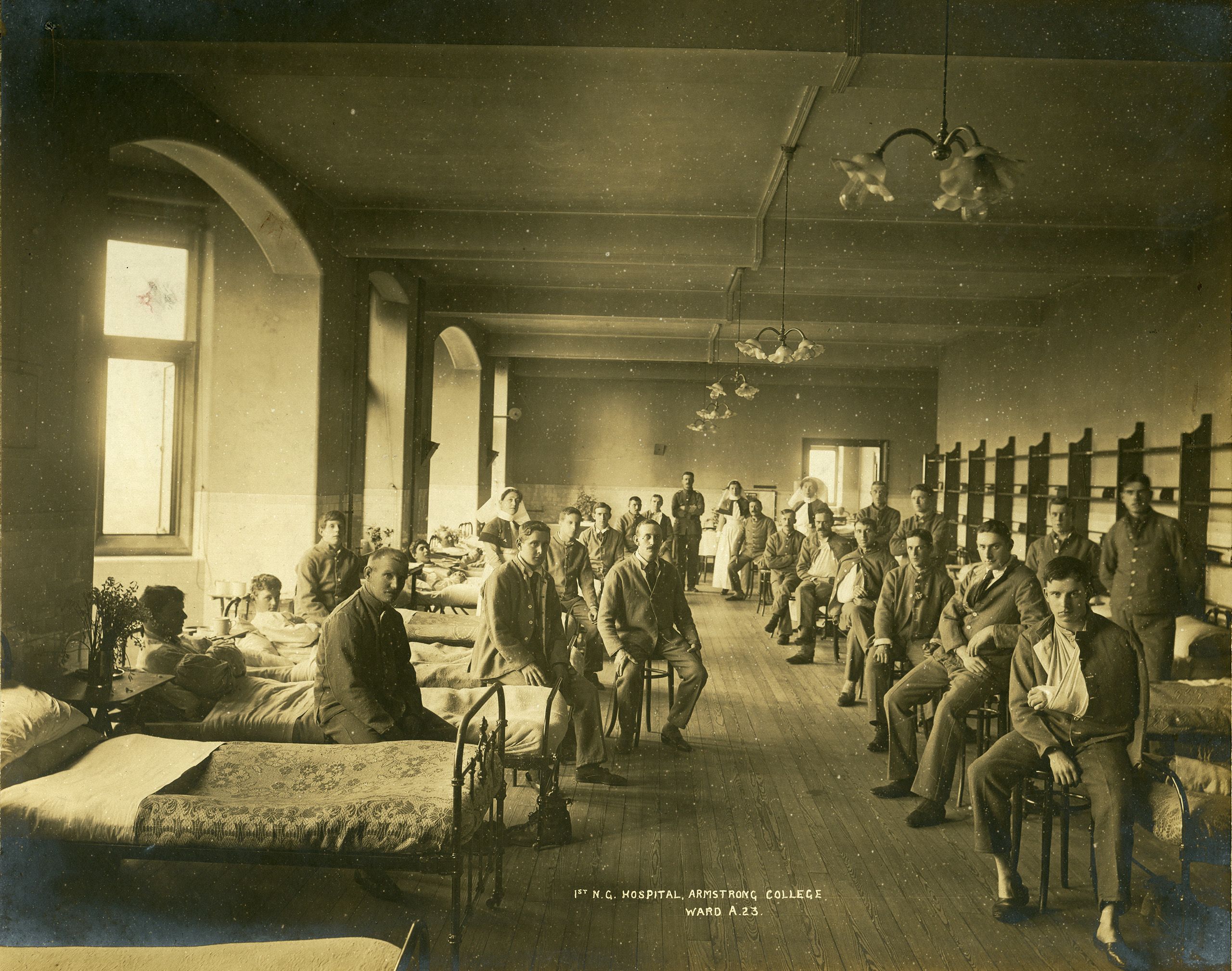

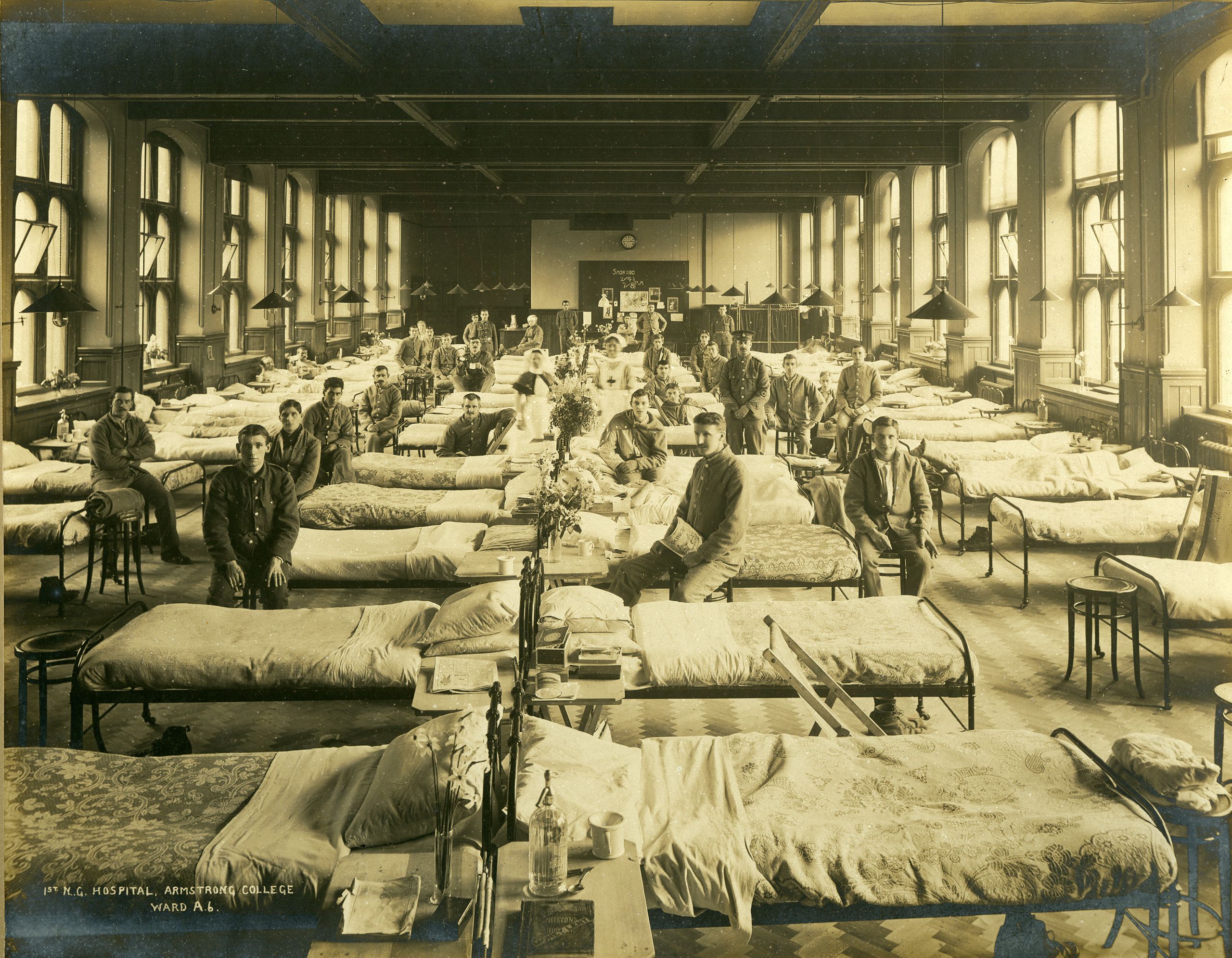

Life on the Wards of the First Northern General Hospital

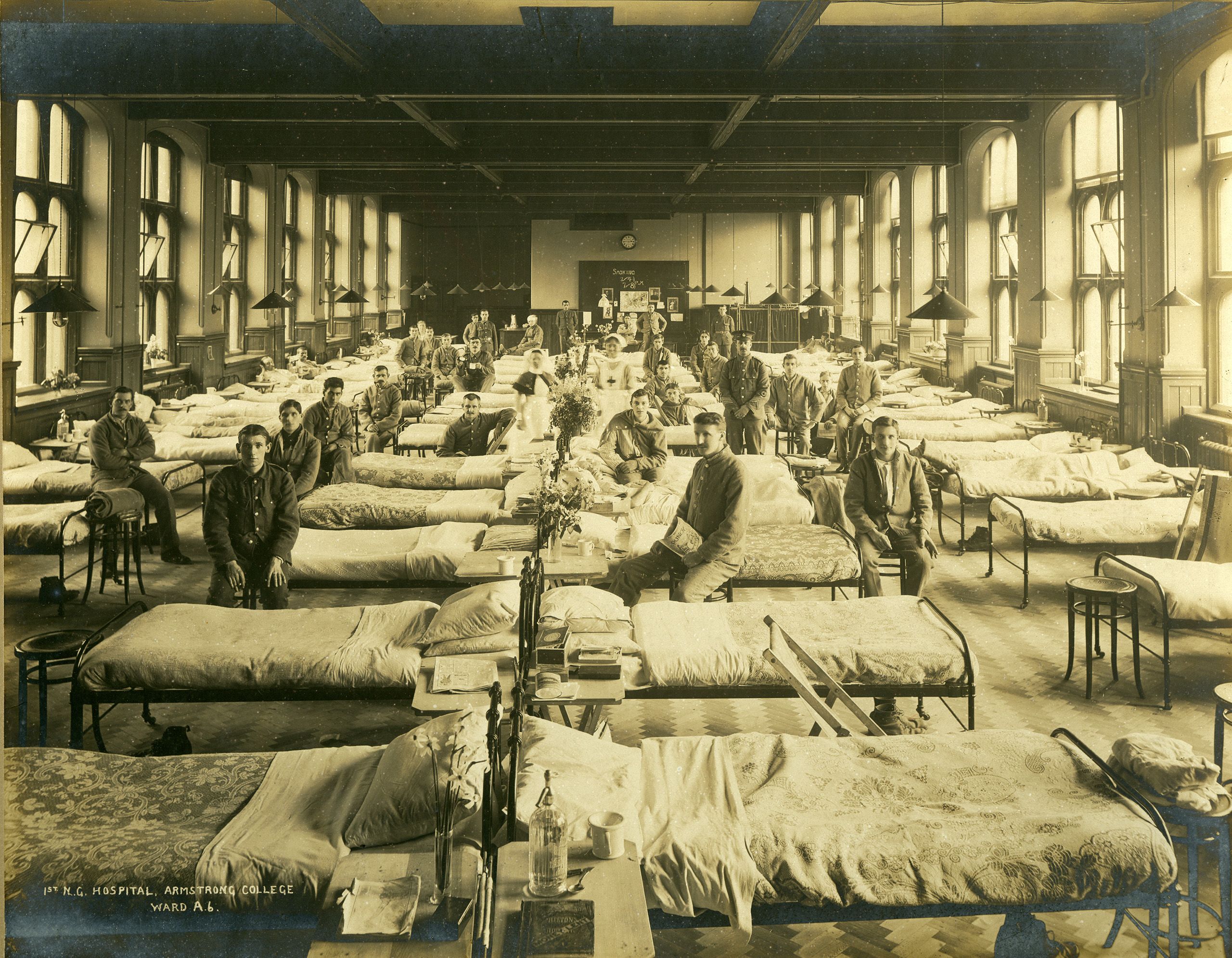

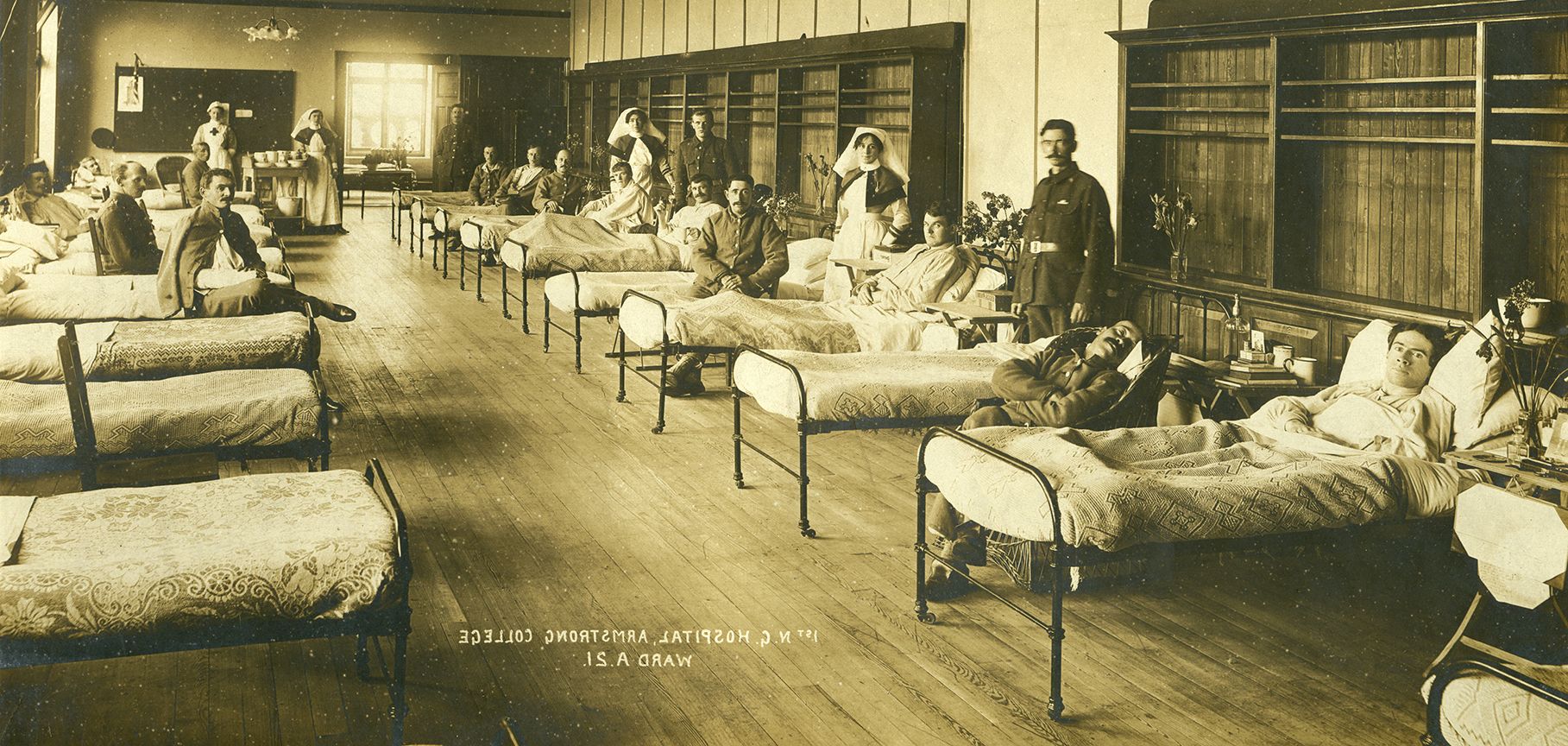

Life on the Wards

Over the course of the war, Newcastle University as the First Northern General Hospital took in at least 41,896 servicemen; both from home and overseas. Wounded from France were taken from one of several south coast ports by ambulance train to one of the hospitals, being treated on route. This would often be a slow process and such convoys would be a spectacle and a focal point for local people. In theory, the wounded could request a hospital near their home, but this may have actually been more to do with where there were vacancies. We know of at least 2 alumni of the University who did come back to be treated with differing outcomes.

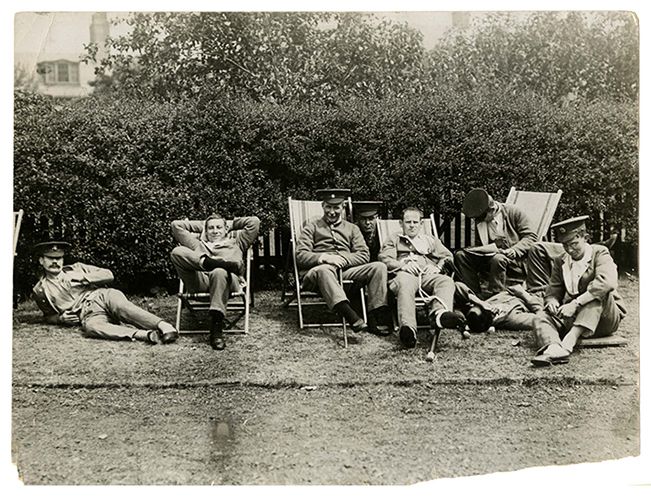

From what we know about life on the wards from photographs and rare written sources, the soldiers would pass the time when they were well enough relaxing in the grounds, smoking, reading, and undertaking handicrafts such as lace work and embroidery.

Photograph of wounded servicemen resting in deckchairs, NUA/041017-08

Photograph of wounded servicemen resting in deckchairs, NUA/041017-08

When they were well enough to venture outside the walls of the hospital, they wore distinctive pale blue flannel suits and red ties to identify them as wounded personnel. A stigma existed for men of military age remaining at home as accusations of cowardice would often arise.

Photograph of wounded servicemen smoking outside the Armstrong Building, NUA/041017-05

Photograph of wounded servicemen smoking outside the Armstrong Building, NUA/041017-05

The wounded are reported as being treated very well by local people and were often sent sweets, tobacco, and other luxury goods.

Background image: Photograph of wounded servicemen and staff on Ward A of the First Northern General Hospital, NUA/041017-21

Read and Recuperate

A popular way to pass the time both on the trenches and on the wards, was by reading magazines and comics making light of the conflict. Punch magazine (as read by the man in the image on the right, on Ward A.6 of the First Northern General Hospital) was an immensely popular satirical paper similar in tone to today’s Private Eye. It was seen as an unbiased view of the war, using comedy in a cathartic way to assuage the growing fears of the public at large.

Where Punch was aimed at a middle class readership, the Bystander, a weekly tabloid magazine, offered a much more popular view. Its height of popularity came during World War I, largely because of Captain Bruce Bairnsfather’s regular cartoons depicting life in the trenches. These were often considered crude and vulgar for the time, typically demonstrating a gallows humour soldiers could identify with.

Captain Bruce Bairnsfather (1887 - 1959). Having been hospitalised himself with shellshock in 1915, Bruce developed his morale boosting cartoons on trench life. Their popularity earned him a promotion and receipt of a War Office appointment to draw for the forces.

Captain Bruce Bairnsfather (1887 - 1959). Having been hospitalised himself with shellshock in 1915, Bruce developed his morale boosting cartoons on trench life. Their popularity earned him a promotion and receipt of a War Office appointment to draw for the forces.

In 1915, the Northumberland Handicrafts Guild suspended most of their activities to concentrate on providing classes to wounded soldiers; one of the first organisations to take up this calling as the need for some definite employment was required. A complaint from a soldier at the First Northern General Hospital led several ladies to volunteer their time and expertise in instructing on leather-work, basket-making, rug-making, and embroidery.

A certificate issued by Northumberland Handicrafts Guild to Margaret Scott for an exhibit of embroidery, 1912, NHG/6 (Northumberland Handicrafts Guild Archive)

A certificate issued by Northumberland Handicrafts Guild to Margaret Scott for an exhibit of embroidery, 1912, NHG/6 (Northumberland Handicrafts Guild Archive)

These wounded soldier classes led to ten exhibitions with prizes over the course of the war, the majority held in King's Hall in theArmstrong Buildings. These pieces were sold and all profits given to charities, amounting to £342 11s. 4d. by the end of the war. The Queen was also given specimens of the men’s work on the Royal Visit to Newcastle in 1917.

The Guild returned to its original activities in March 1919. As related in the Annual Reports however, both the Guild and medical staff felt the work was hugely beneficial in aiding the recovery of those wounded. They even adapted their teaching styles to account for the tastes of the patients, but the Honrary Secretary does comment “A restraining influence had occasionally to be applied when men wanted to develop so-called crafts that the Guild did not want to encourage.”

Background image: Section from photograph of wounded servicemen and staff on Ward A6 of the First Northern General Hospital, showing a serviceman holding PUNCH magazine, NUA/041017-12

Home for Christmas

What was it like at Christmas on the First Northern General Hospital? These 3 postcards from the University Archives (below) consist of images taken on the wards and feature both patients in flannel suits and ties, Royal Army Medical Corps personnel in uniforms, nurses, and the matron.

A note on the back of all 3 tell us they were taken around Christmas 1915 on wards on the ground floor of the Armstrong Building and were sent by a ‘D. Robinson’ to an address in Corbridge, Northumberland.

Life on the Wards:

THEN and NOW

Scroll down to reveal photographs of University buildings that accommodated the First Northern General Hospital.

Uncover what they looked like THEN between 1914-1919 and what they look like NOW, 100 years on.

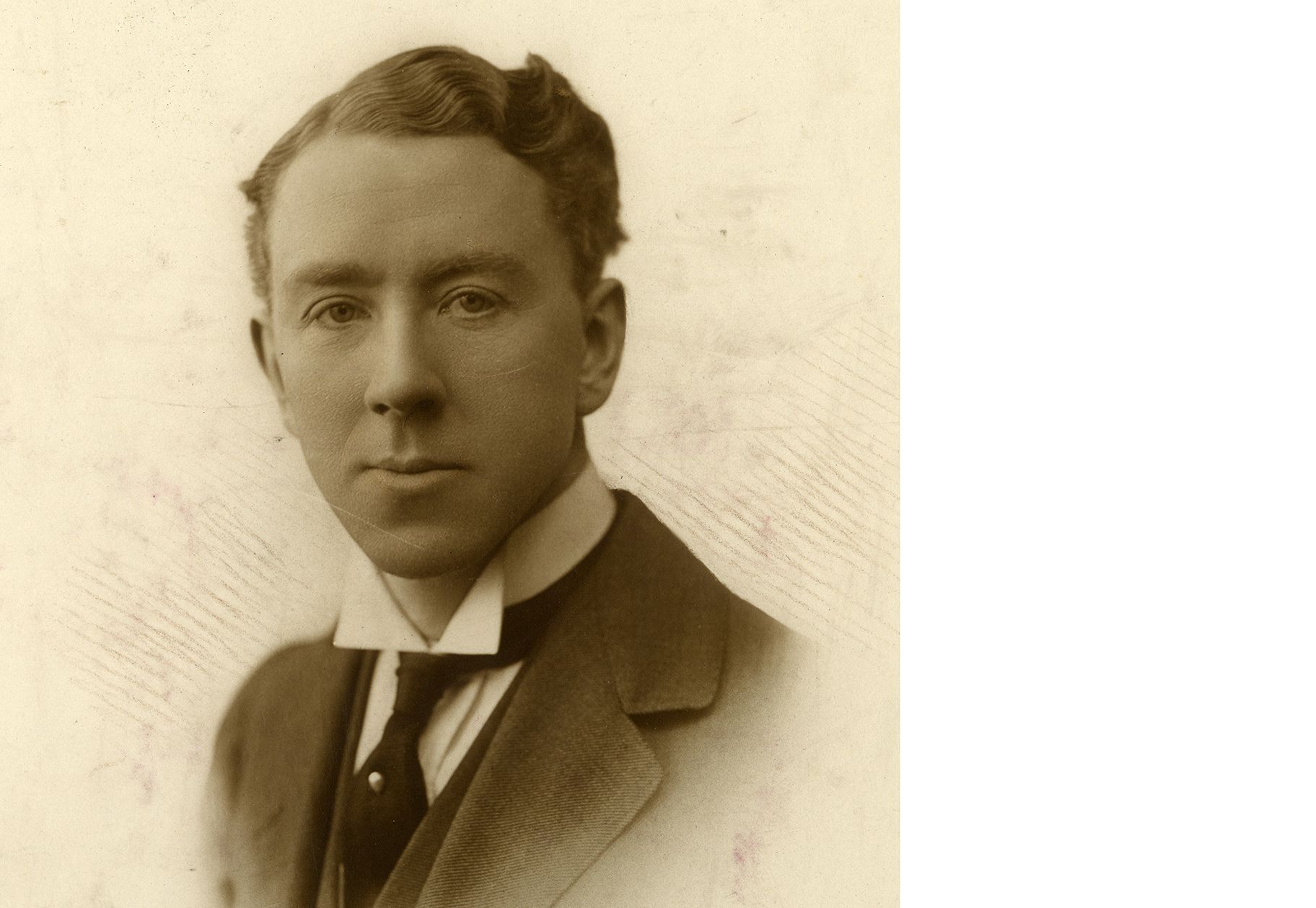

Professor Pybus:

Surgeon/Inventor/Pioneer/Scholar

Professor Frederick Charles Pybus (1883 - 1975)

Pybus was a surgeon and alumni of our College of Medicine, graduating in 1905. He joined the First Northern General Hospital shortly after its formation and was serving as its Registrar in 1914. As a Major in the Royal Army Medical Corps, except for a brief posting at the 17th General Hospital in Egypt, he served as a surgeon at Armstrong College throughout the war. Up until 1919, he carried out at least 1,364 operations on wounded servicemen.

Professor Pybus went on to have a distinguished career as a surgeon in the Royal Victoria Infirmary from 1920 until his retirement in 1944, becoming Professor of Surgery in the College of Medicine in 1941. Amongst his claims to fame was inventing a drink to sustain patients before operations, which was later developed and sold by a local chemist to Beechams, becoming Lucozade.

His lifelong concerns included cancer research, developed during his 50 year surgical career from 1924 and pursued through his own cancer research laboratory. He was amongst the first to make the link to atmospheric pollution as a major contributing cause of cancer and his work directly informed the Clean Air Act 1956.

Page from Cancer and its Cause Part 1, 1959, FP/1/1/2/2/1/25 (Frederick Charles Pybus Archive)

Page from Cancer and its Cause Part 1, 1959, FP/1/1/2/2/1/25 (Frederick Charles Pybus Archive)

For some 40 years Professor Pybus also built up a collection of international importance on the history of medicine, including books, engravings, letters, portraits, busts and bleeding bowls. In 1965, he donated the collection to the Library, where it remains a valuable source of information for medical historians. Find out more in the Pybus (Professor Frederick) Collection and Archive.

Professor Pybus and the First Northern General Hospital

Professor Pybus had been the Registrar of the First Northern General Hospital, joining shortly after it’s formation and serving as Registrar in 1914. As a Major in the Royal Medical Corps, he served briefly at the 17th General Hospital in Alexandria, Egypt between March and November 1915, but for the majority of the war he was a surgeon based on the requisitioned premises of Armstrong College.

Photograph showing Pybus in the operating theatre in the First Northern General Hospital, c. 1915, FP/1/3/9 (Frederick Charles Pybus Archive)

Photograph showing Pybus in the operating theatre in the First Northern General Hospital, c. 1915, FP/1/3/9 (Frederick Charles Pybus Archive)

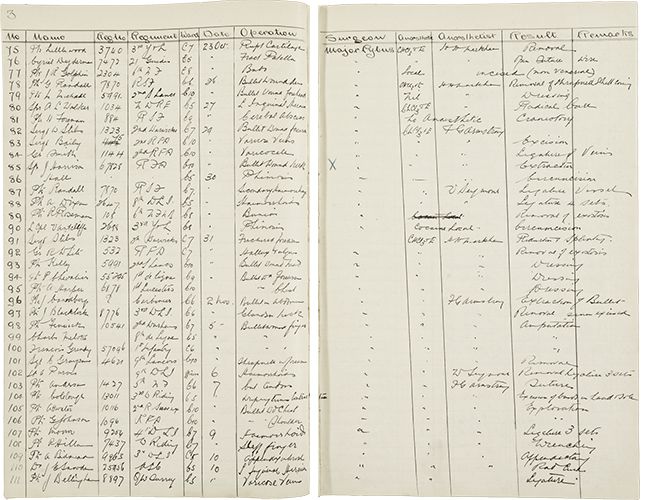

Here, he carried out around 1,364 operations between 14th September 1914 and 12th April 1919, all detailed in his Operation Log Book.

Notebook of Operations undertaken by Frederick Charles Pybus at the First Northern General Hospital, 1915-1919, FP/1/3/8 (Frederick Charles Pybus Archive)

Notebook of Operations undertaken by Frederick Charles Pybus at the First Northern General Hospital, 1915-1919, FP/1/3/8 (Frederick Charles Pybus Archive)

A gap in this log book between the middle of December 1917 and May 1918 and the letters between him and the hospital tells us Pybus suffered from neuritis (inflamed nerves) which led to him being demobilised for a short period. Despite still suffering, he seems to have been forced back against his will, with Pybus concerned he was not capable of performing his often life saving duties.

Professor Pybus and the Origins of Lucozade

A story which has almost passed into local folklore is Professor Pybus’ hand in the creation of a household name; the energy drink Lucozade.

Pybus himself verifies this story in a note present in the archive, which were donated shortly after his books in 1965. He describes how, during his student days working as a House-Surgeon at the Royal Victoria Infirmary in 1908, he lost a young patient following a seemingly successful operation. It was felt that this was because the child was starved, leading to them not being able to break down the chloroform used as an anaesthetic and resulting in a slow poisoning of the liver. This tragic event clearly affected the young Pybus. When he became surgeon at the Fleming Memorial Hospital for Sick Children following his graduation, he made his patients drink a glucose drink he devised prior to surgery and when they had a fever, to stop this happening again.

Short description of Pybus' involvement in the production and use of Lucozade at the Royal Victoria Infirmary in 1908, FP/3/5/26 (Frederick Charles Pybus Archive)

Short description of Pybus' involvement in the production and use of Lucozade at the Royal Victoria Infirmary in 1908, FP/3/5/26 (Frederick Charles Pybus Archive)

An enterprising chemist in Barras Bridge called William Owen provided the ingredients as a prescription, but noticing its popularity started making it himself and indeed perfected the recipe, with Pybus admitting he had “a taste of sulphur bi-oxide which most glucose had in order to prevent fermentation.”

Owen called this drink Glucozade but, in 1938, Beecham pharmaceutical company realised the commercial potential and bought the formulae for the then princely sum of “about £10,000”, and Lucozade was born. Pybus admits in this note that although he had no share in this “I sometimes wish I had”. However, it was clearly a comfort that, in respect of the child that died, Pybus felt on his wards the Lucozade prototype “prevented this happening so far as I know for ever afterwards.”

Background image: Photograph of Frederick Charles Pybus, c.1905, FP/3/4/32 (Frederick Charles Pybus Archive)

Aftermath:

The Scars of War

Aftermath

As well as losing 276 former students and teaching staff, Newcastle University struggled to recover from World War I in more practical terms as well. In October 1919 Armstrong College was ready to receive its first intake of ex servicemen, but by then was in poor shape. It had housed the greater part of the First Northern General Hospital since 6th August 1914 at the expense of its teaching, further exacerbated by the fact that most men and women of university age were engaged in the war effort. It had become badly resourced and was offered little compensation.

Photograph of The Quadrangle facing the arches, pre 1949. The auxiliary Army huts erected during World War I remained on site right up until after World War 2, operating as makeshift classrooms

Photograph of The Quadrangle facing the arches, pre 1949. The auxiliary Army huts erected during World War I remained on site right up until after World War 2, operating as makeshift classrooms

During the war the College buildings were given up to the care of the sick and wounded, and it was a perfectly equipped hospital. Then came the peace, and the College made efforts for training and educating those who had not been fighting, which, with its work in teaching the rising generation, was almost too much for its finances. He introduced this matter because it was part of the history of the College, and it was the history of an institution which went to make esprit de corps. He believed the war chapter in the College’s history would be of great value to it in future.

Today, this prediction has proved accurate. The work of the First Northern General Hospital has helped form the basis for our commemorations, helping us to understand how lives both at home and abroad were ended or put on hold for this devastating conflict.

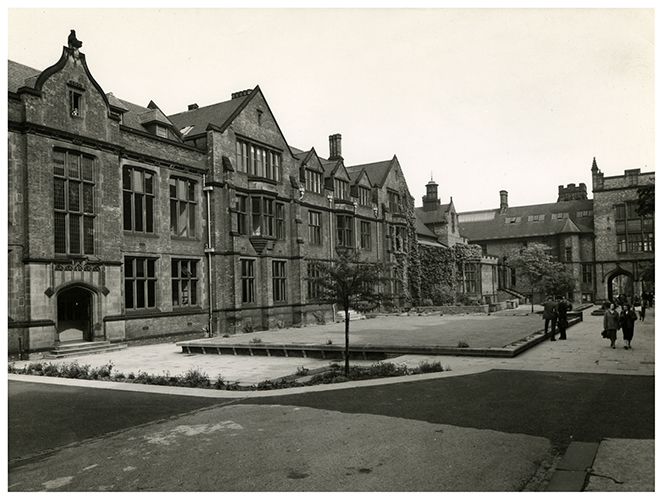

The Quadrangle, 1955...

The below photograph shows the quadrangle in its current, more recognisable state. Having recovered from its requisition in both World War 1 and World War 2, Newcastle University was allowed to grow to its full potential unimpeded. Remembering its debt to those who served however, in 1949 the Quadrangle Garden was laid out in memory of all members of Newcastle University who gave their lives in both wars.

Photograph of The Quadrangle, 1955

Photograph of The Quadrangle, 1955

The Memorial Garden is now the focus and venue for the service every Remembrance Sunday.

Photograph of the Memorial Garden plaque, in memory of all members of the Newcastle division of the University of Durham who gave their lives in the First and Second World Wars

Photograph of the Memorial Garden plaque, in memory of all members of the Newcastle division of the University of Durham who gave their lives in the First and Second World Wars

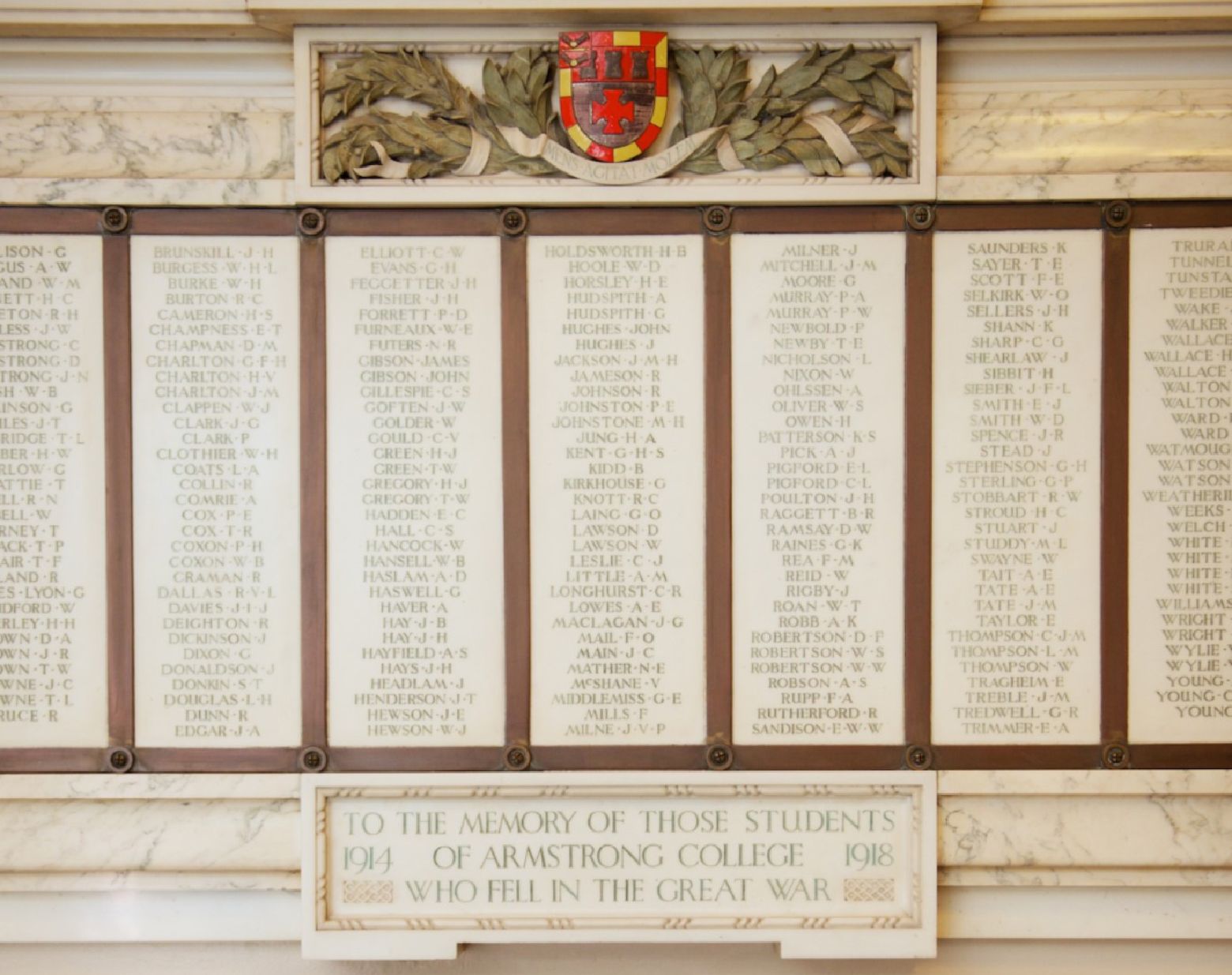

The Armstrong Memorial

The Armstrong Memorial still stands today located in the foyer of the Armstrong Building. It was unveiled in 1923 and lists 223 who lost their lives during the First World War from Armstrong College.

Photograph of the Armstrong Memorial

Photograph of the Armstrong Memorial

At the 1923 unveiling, an address by the Chairman of Armstrong College Council Dr C. A. Cochrane was reported in the Durham University Gazette:

"During the war the College buildings were given up to the care of the sick and wounded, and it was a perfectly equipped hospital. Then came the peace, and the College made efforts for training and educating those who had not been fighting, which, with its work in teaching the rising generation, was almost too much for its finances. He introduced this matter because it was part of the history of the College, and it was the history of an institution which went to make esprit de corps. He believed the war chapter in the College’s history would be of great value to it in future."

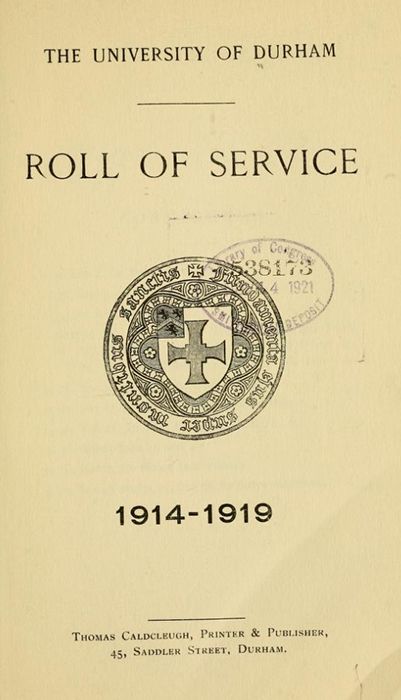

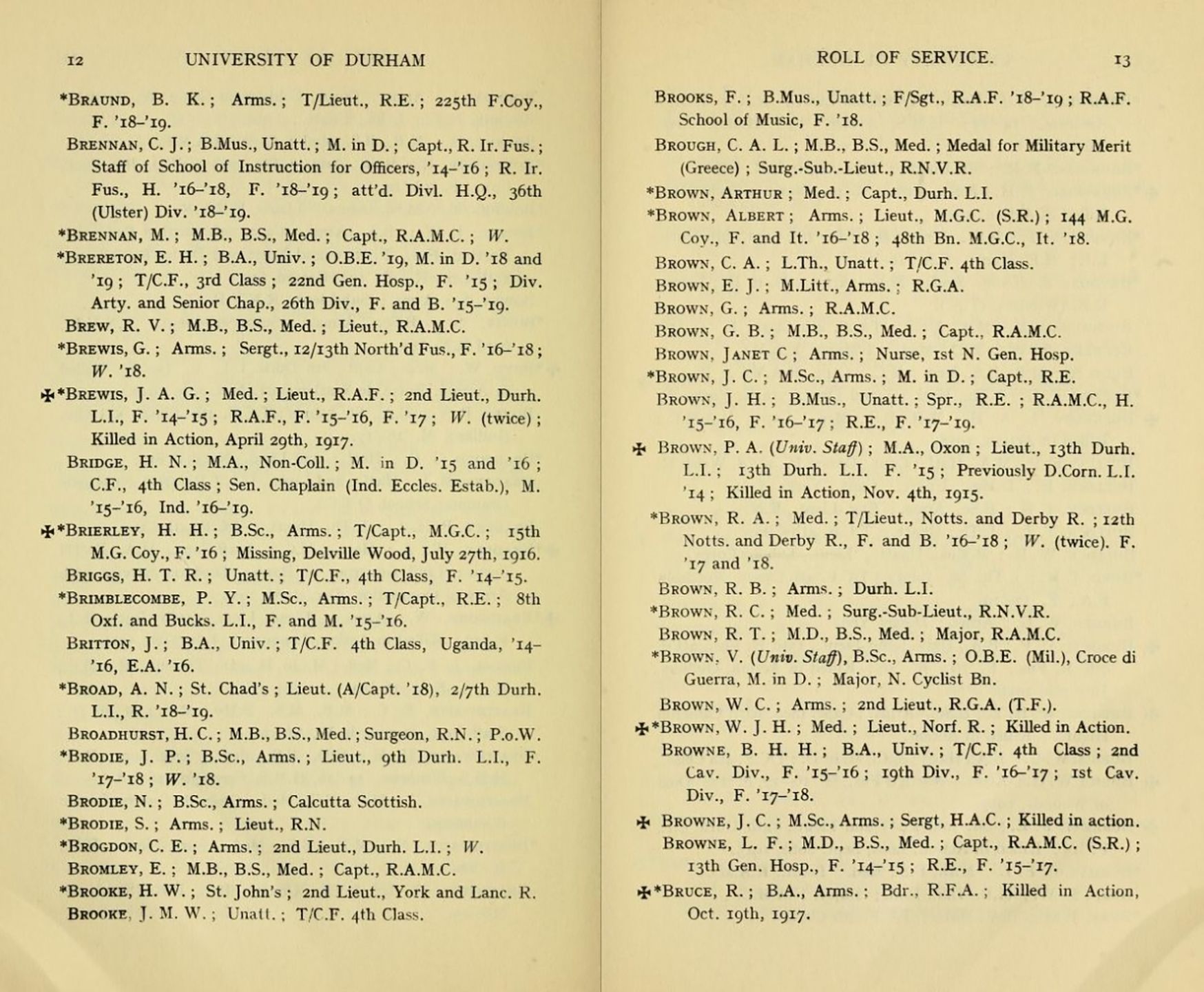

The Roll of Service

The Roll of Service produced in 1920 offers us a partial picture of the ultimate sacrifices made by Newcastle University staff and students. It lists 2,464 that served, both from Armstrong College and the College of Medicine as predecessors to Newcastle University, and Durham University itself, along with its other colleges. Included are basic details on ranks and regiments, honours and decorations, where they served, and where relevant if they were wounded or killed in action.

The University of Durham Roll of Service, 1914-1919, NUA/15/1

The University of Durham Roll of Service, 1914-1919, NUA/15/1

Despite being a useful source, it is only a partial record. 64 of the fallen on the Armstrong Memorial are not included in the Roll of Service and several anomalies, like misspellings of names, exist between the two. This may have been due to difficulties in working with “very meagre War Service details”. A further disclaimer at the beginning of the Roll states “It is also to be feared that, as is almost inevitable in such publications, the names of many of those eligible will be missing altogether.”

Background image: Extract from The University of Durham Roll of Service, 1914-1919, NUA/15/1

A Call to Action:

Universities at War Project

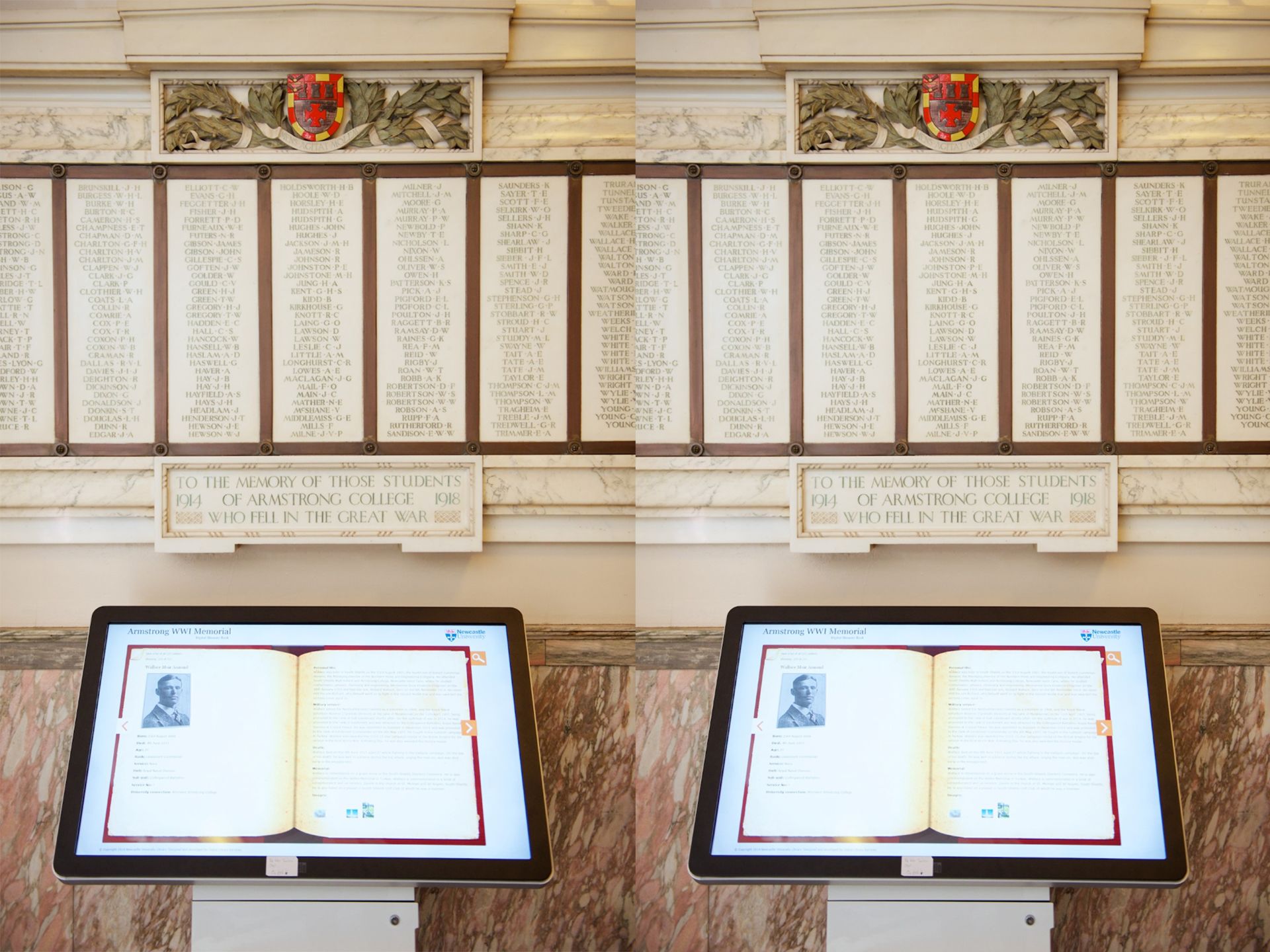

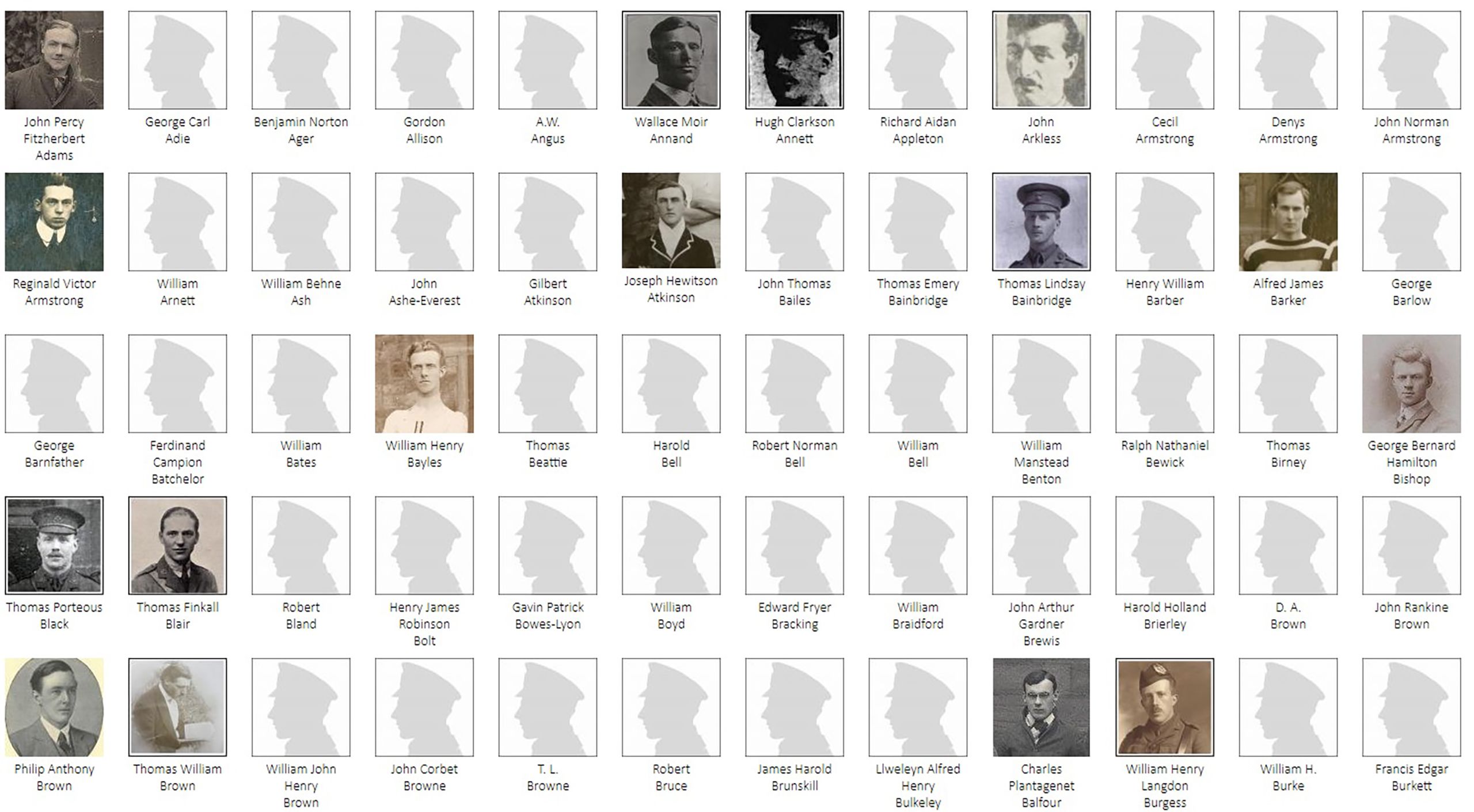

Universities at War was a collaborative HLF-funded First World War project led by Newcastle and Durham Universities in which volunteers conducted research to be able to tell the stories of the fallen associated with both institutions whether students, alumni, or staff. Searching through class lists, course handbooks, registration documents, graduation lists and student magazines, they have slowly pieced together the lives of those who appeared simply as a list of names on Newcastle and Durham University's war memorials of these two inst.

As part of the project, a digital memory book was created, to tell the stories of the fallen. You can browse and search these fallen servicemen on the Universities at War website.

At the time of the First World War, these two institutions were united within the larger University of Durham (Newcastle University was formed in 1923 under the Universities of Durham and Newcastle upon Tyne Act 1963). Also, the university and its associated colleges comprised an unusual group of technical and professional institutions, with a strong local student and alumni body, and more traditional colleges, with a wider national and international population. Universities at War therefore offers a view of the lives of an unusual group of men from all over the country and across diverse socio-economic groups.

Huge thanks must go to our team of volunteers, without whom none of this could have been achieved, and to those with a personal connection to our servicemen whose willingness to contribute family stories and photographs has so enriched this resource.

Background image: Photograph of the Universities at War digital memory book, in front of the Armstrong Memorial

The Fallen:

Alumni Casualties of the First World War

We know around 800 individuals who taught at or attended Armstrong College and 721 from the College of Medicine served in the First World War; a total of 1,521. We also know at least 223 from Armstrong College and 53 from the College of Medicine made the ultimate sacrifice and died in the fighting.

From newspaper accounts reporting on the unveiling of the Armstrong Memorial on 23rd April 1923, 106 Armstrong soldiers, or around 16% were wounded. This meant nearly half of those who served from Armstrong College alone were either killed or wounded. 97 were mentioned in dispatches and a total of 225 honours were won for bravery.

Scroll below to read some of stories of the fallen alumni listed on the Armstrong Memorial...

Captain Henry Clifford Stroud

Royal Flying Corps, 61st Squadron

Date of Death: Thursday, 7 March, 1918.

Age 24

Henry was born in July 1893 in Newcastle upon Tyne.

He was a Student of the Institution of Civil Engineers, and elected a Graduate of the North East Coast Institution of Engineers and Shipbuilders in 1910. While at Armstrong College, Henry spent two years in the University Officers' Training Corps.

At the outbreak of war he immediately volunteered for foreign service, proceeding to France in January 1915 with the Northumbrian Royal Engineers, 1st Field Company. He was severely wounded in both legs on 8th February 1915.

He returned to Armstrong College, which had then become the First Northern General Hospital, and spent many months recovering there. Owing to the nature of his wounds it was impossible that he should resume active field work.

In June 1916, Henry obtained his Captaincy. Wishing to take a more active part in the War, he joined the Royal Flying Corps. He soon qualified for his wings, was gazetted pilot in September 1916, and speedily became an expert flier.

In the early autumn of 1917 he joined the defence of London and was stationed at Rochford Aerodrome with 61st Squadron. Henry was engaged in repelling practically every German air raid on London until the penultimate raid.

He was killed flying around midnight on 7th March 1918 in Essex; the only night the Germans raided when there was no moon. He took off in an Se5a B679 at 23:30 hours to intercept a German raider heading for London. A minute earlier Alexander Bruce Kynoch of 37 Squadron based at Stow Maries had taken off in a BE12 C3208 to intercept the same raider. In the darkness the two aircraft collided and fell in Dollymans Farm, Essex.

Background image: Photograph of Captain Henry Clifford Stroud

Major Alexander Kirkland Robb

Durham Light Infantry, 2nd Battalion

Date of death: Sunday, 20 September, 1914

Age 42

Born in 1872 in India, his father was Lieutenant Colonel John Robb of the Indian Medical Service. He was educated in Aberdeen and, on selecting the Army as his career, he went to the Royal Military College at Sandhurst. Here, in January 1893, he obtained the sword of honour and passed out first in his year.

He was posted to the Durham Light Infantry, 2nd Battalion, on 20th May 1893, then serving in India.

After this early active service, in 1912 Alexander came to Newcastle, becoming involved in instructing the University’s Officer Training Corps and later being appointed Lecturer in Military History.

On the outbreak of World War I, he was mobilised to Northern France and saw his first engagement at the Battle of Aisne. Whilst leading a counter attack on 20th September 1914, he was severely wounded in a bayonet charge, but continued to lead his men up to around 30 yards from the German trenches.

2 men from his battalion carried him back to the British trenches whilst under fire, one of whom was wounded and the other killed performing this brave action. He died from his wounds in a hospital at Troyon the same night. Alexander is the second oldest of the fallen from Armstrong College at 42 and one of six Majors; the highest rank to feature.

Background image: Photograph of Major Alexander Kirkland Robb

Lieutenant Commander Wallace Moir Annand

Royal Naval Division, Collingwood Battalion

Date of death: Friday, 4 June, 1915

Age 26

Wallace was born in South Shields on the 23rd August 1887. He was the fourth son of Robert Cummings Annand. He was educated at South Shields High School and then Armstrong College, where he studied Mathematics, Physics, Chemistry and Engineering. He married Dora Elizabeth Chapman on the 10th January 1914 and they had one son, Richard Wallace, born on the 5th November 1914. He never met his son, who himself went on to fight in the Second World War and was awarded the Victoria Cross aged 25. Wallace joined the Northumberland Fusiliers as a volunteer in 1904, and the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (Tyneside Division) at the rank of Midshipman on the 11th April 1907, being promoted to the rank of Sub-Lieutenant shortly after.

On the outbreak of war in 1914, he was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant and was attached to the Royal Naval Division, Collingwood Battalion at Crystal Palace. He was appointed as Adjutant in December 1914 and was promoted to the rank of Lieutenant-Commander on the 8th May 1915.

Wallace died on the 4th June 1915 aged 26 whilst fighting in Gallipoli.

Background image: Photograph of Lieutenant Commander Wallace Moir Annand

Find Out More

Newcastle University Library Special Collections & Archives collects, preserves, promotes and provides access to unique and distinctive books and archives. These resources are made available not only to our own University staff and students, but to researchers from other institutions and to the wider community.

To find out more about our holdings please look at our Collections Guide. To discover how you can consult materials see Using our Collections.

You can also find out more about the individuals on Newcastle and Durham Universities World War I memorials by visiting the Universities at War website.