Alexander Pope

and his Books

An exhibition focusing on the extraordinary collection of books in Newcastle University’s Special Collections & Archives and other libraries. These books were once owned, annotated, or given as gifts by the eighteenth century poet, Alexander Pope.

Alexander Pope became the most celebrated poet of the eighteenth century. He was also an obsessive purchaser, reader, annotator, and designer of books. This obsession with the material form of the printed book began in childhood and stayed with him throughout his life.

This exhibition focuses on an extraordinary collection of books in Newcastle University Special Collections and Archives (Philip Robinson Library), that were once owned, annotated, or given as gifts by Pope, while also drawing connections with books owned by Pope that are now in other libraries. It explores what Pope did with his books: how he engaged with them, harnessed them as creative resources for his own writing, and used them to build and sustain friendships.

Childhood Books

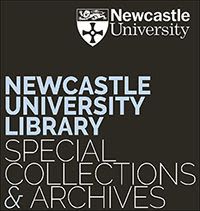

One of the very first books that Pope purchased as a boy was this copy of Cervantes’s Don Quixote, newly translated into English in 1700 by Peter Motteux. Pope bought the first two volumes of this translation as soon as they were published, spending two shillings. He was only twelve years old.

At the front of volume one, Pope cited with approval the judgement of the Jesuit scholar René Rapin on the genius of Cervantes. As a boy, Pope taught himself to write by copying printed books and this inscription is an excellent demonstration of his early eye for calligraphy.

Miguel de Cervantes. The History of the Renown’d Don Quixote de la Mancha, trans. Peter Motteux (1700): Harvard, Houghton Library, Hyde Collection *2003J–EC322

Miguel de Cervantes. The History of the Renown’d Don Quixote de la Mancha, trans. Peter Motteux (1700): Harvard, Houghton Library, Hyde Collection *2003J–EC322

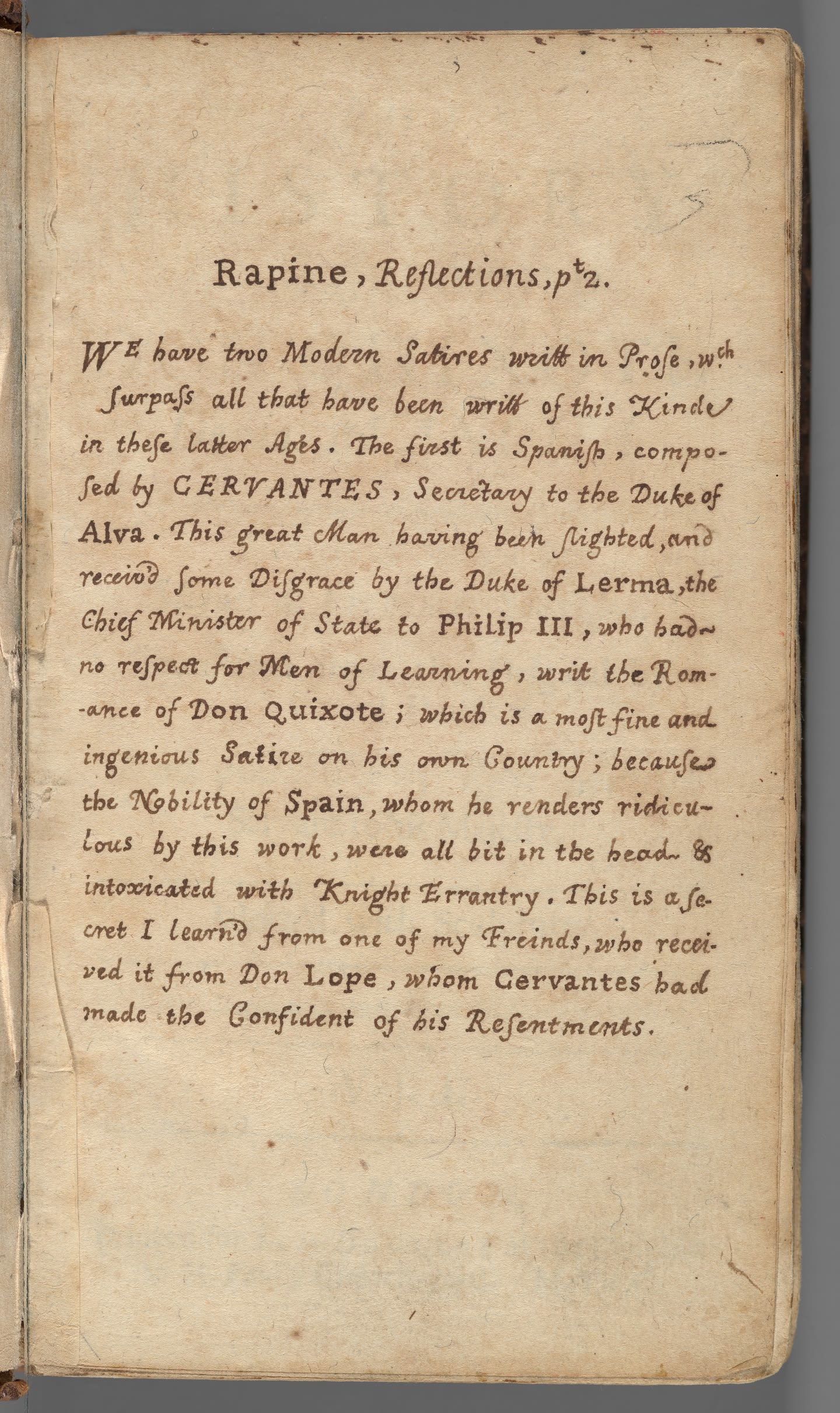

Another early purchase was this copy of Thomas Stanley’s encyclopaedic The History of Philosophy, in the huge new folio edition published in 1701. This copy cost fourteen shillings, which was a huge amount of money for Pope, who was still only thirteen. The typographic style of the inscription, with the first line in bold roman and the second in swash italic capitals, is near identical to that in the front of Pope’s copy of Chaucer (now at Hartlebury Castle), which is dated to 1701.

Ownership inscription to Thomas Stanley, in The History of Philosophy, by Thomas Stanley (1701) (Philip and Marjorie Robinson Collections, Robinson 409).

Ownership inscription to Thomas Stanley, in The History of Philosophy, by Thomas Stanley (1701) (Philip and Marjorie Robinson Collections, Robinson 409).

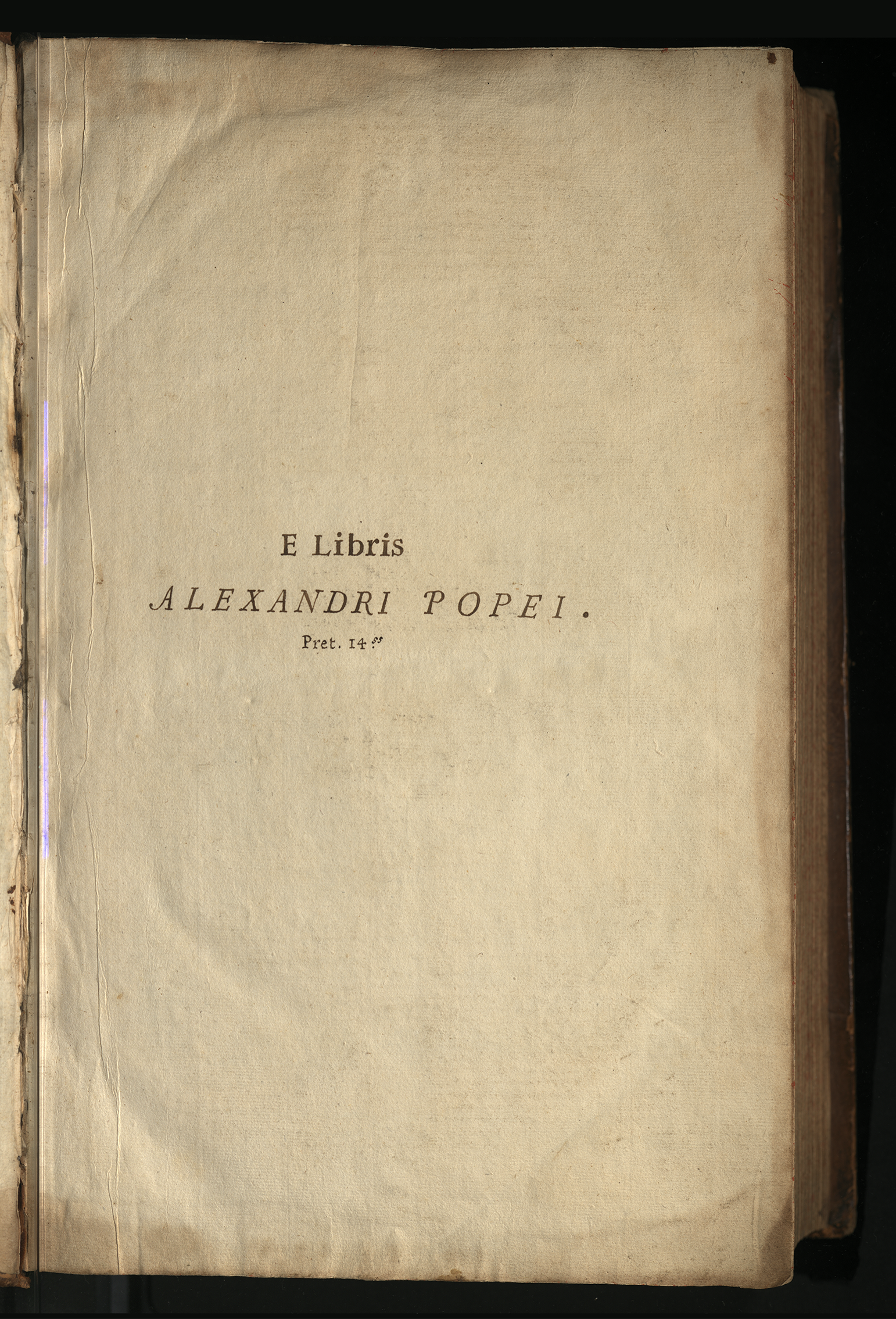

The book was evidently carefully read. In the Life of Pythagoras chapter, Pope corrected a sentence by inserting the word ‘not’ in tiny letters.

Extract The History of Philosophy, showing Pope correcting a sentence by inserting the word 'not' (Robinson 409).

Extract The History of Philosophy, showing Pope correcting a sentence by inserting the word 'not' (Robinson 409).

As a teenager, Pope was engaged in a programme of translating the Greek and Latin classics into English heroic couplets, the form for which he would soon become famous. Following his fourteenth birthday in 1702, he translated the first book of Statius’s epic poem, the 'Thebaid', which he later exhumed and published with other verses in 1712.

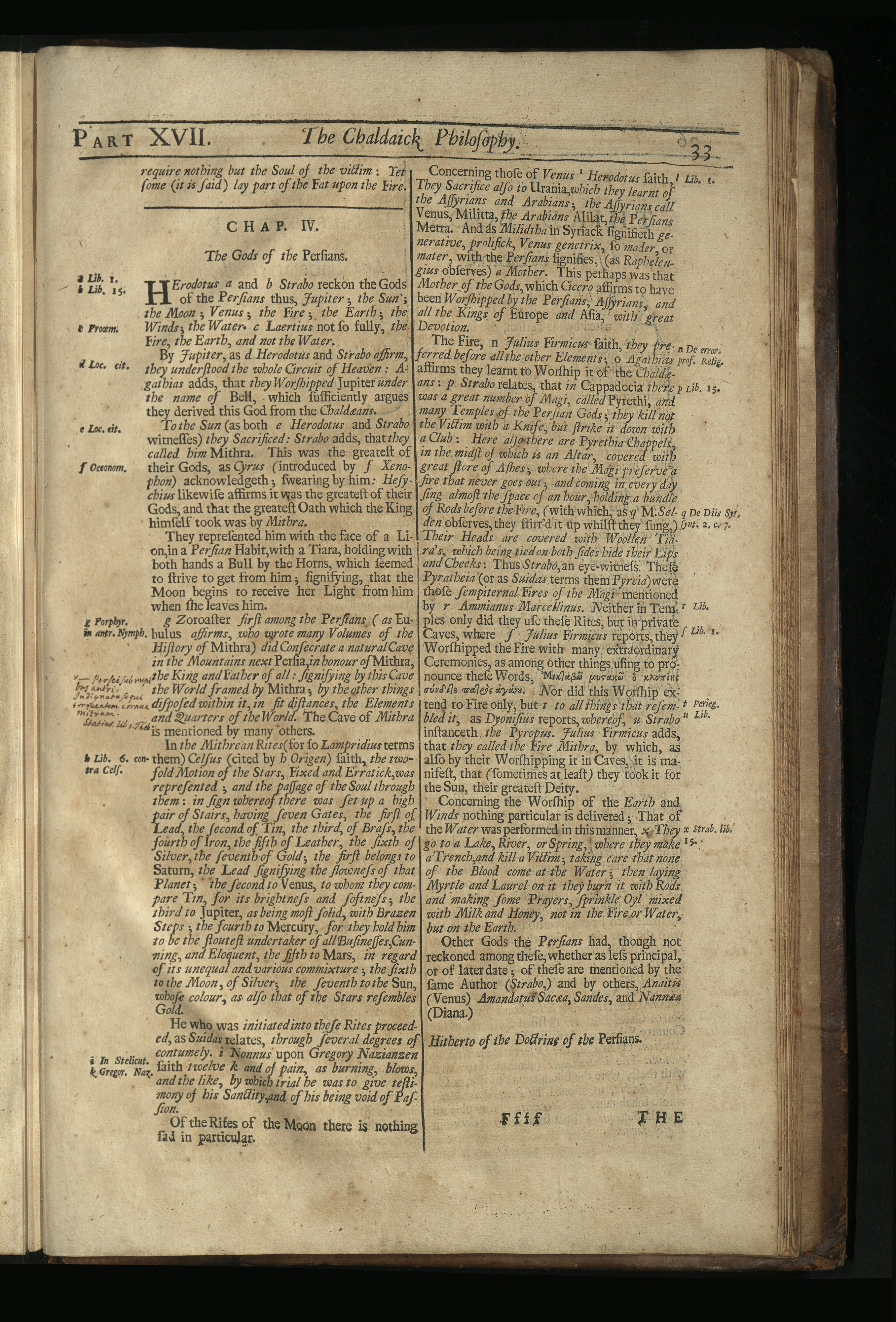

Page from Statius' Thebaid from Stanley's History of Philosophy (Robinson 409).

Page from Statius' Thebaid from Stanley's History of Philosophy (Robinson 409).

Here we see Pope quoting a relevant line from the 'Thebaid' next to a passage mentioning the ‘Cave of Mithra’. Efforts have been made to keep the handwriting as close as possible in size and style to the printed italic notes in the margin. The implication is that Pope was very probably reading this folio of Stanley while making his translation.

Extract from Statius' Thebaid written by Pope in the margin of Stanley's History of Philosophy (Robinson 409).

Extract from Statius' Thebaid written by Pope in the margin of Stanley's History of Philosophy (Robinson 409).

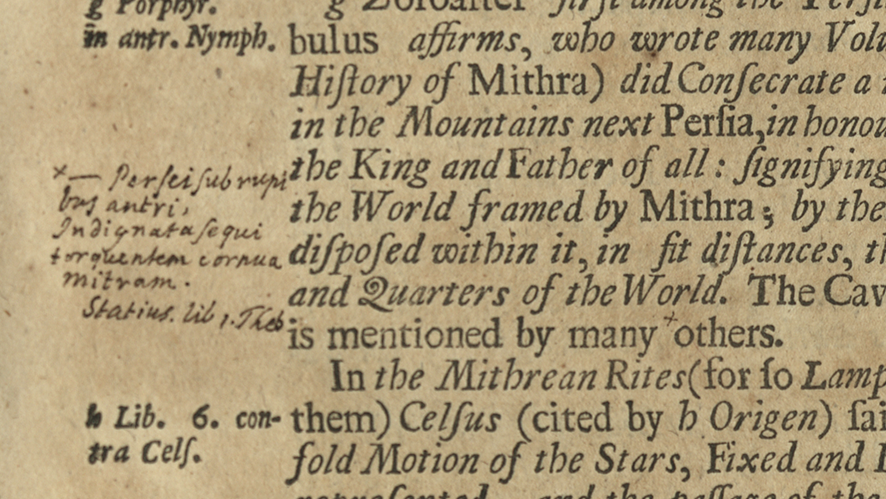

One of the most significant texts in Pope’s early development as a writer was John Milton’s epic poem Paradise Lost, first published in ten books in 1667, and then later reorganised into twelve books in 1674. We know he had access to the ten-book quarto published in 1669, though this copy has never been found. Here we have his copy of the illustrated fifth edition of 1705. On the title page, immediately below ‘In Twelve Books’, in Pope’s later teenage ‘print’ hand, he has written: ‘First publish’d in Ten Books, in the year, 1669. Quarto’

Title page from Paradise Lost: A Poem in Twelve Books, by John Milton (1705) (Marjorie and Philip Robinson Collection, Robinson 61).

Title page from Paradise Lost: A Poem in Twelve Books, by John Milton (1705) (Marjorie and Philip Robinson Collection, Robinson 61).

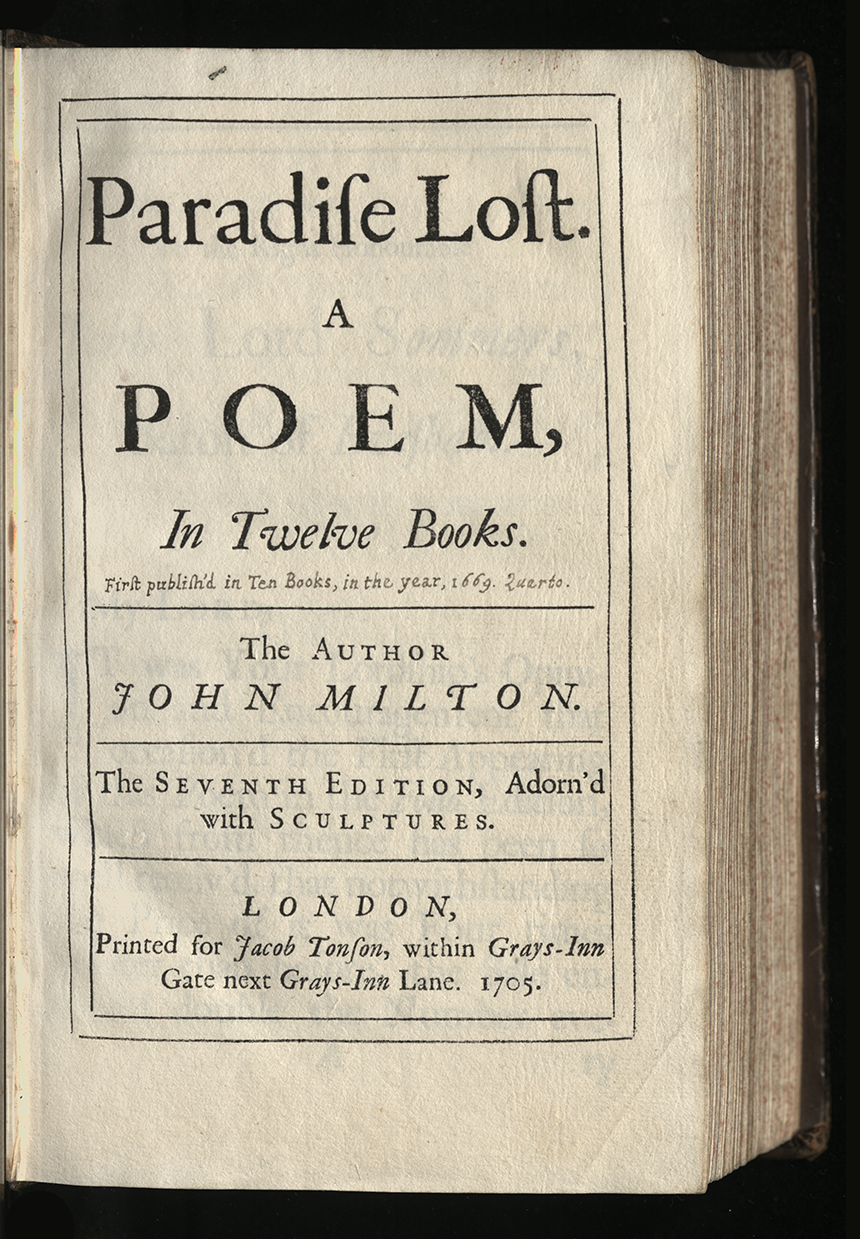

Inside the book, Pope has inserted a preliminary note printed in the earlier edition but excluded from this one. It appears alongside a note of his own, explaining that he believed these lines to have been ‘written by Milton himself’.

Note on a page in Paradise Lost: A Poem in Twelve Books, explaining that he believed these lines to have been ‘written by Milton himself’ (Robinson 61).

Note on a page in Paradise Lost: A Poem in Twelve Books, explaining that he believed these lines to have been ‘written by Milton himself’ (Robinson 61).

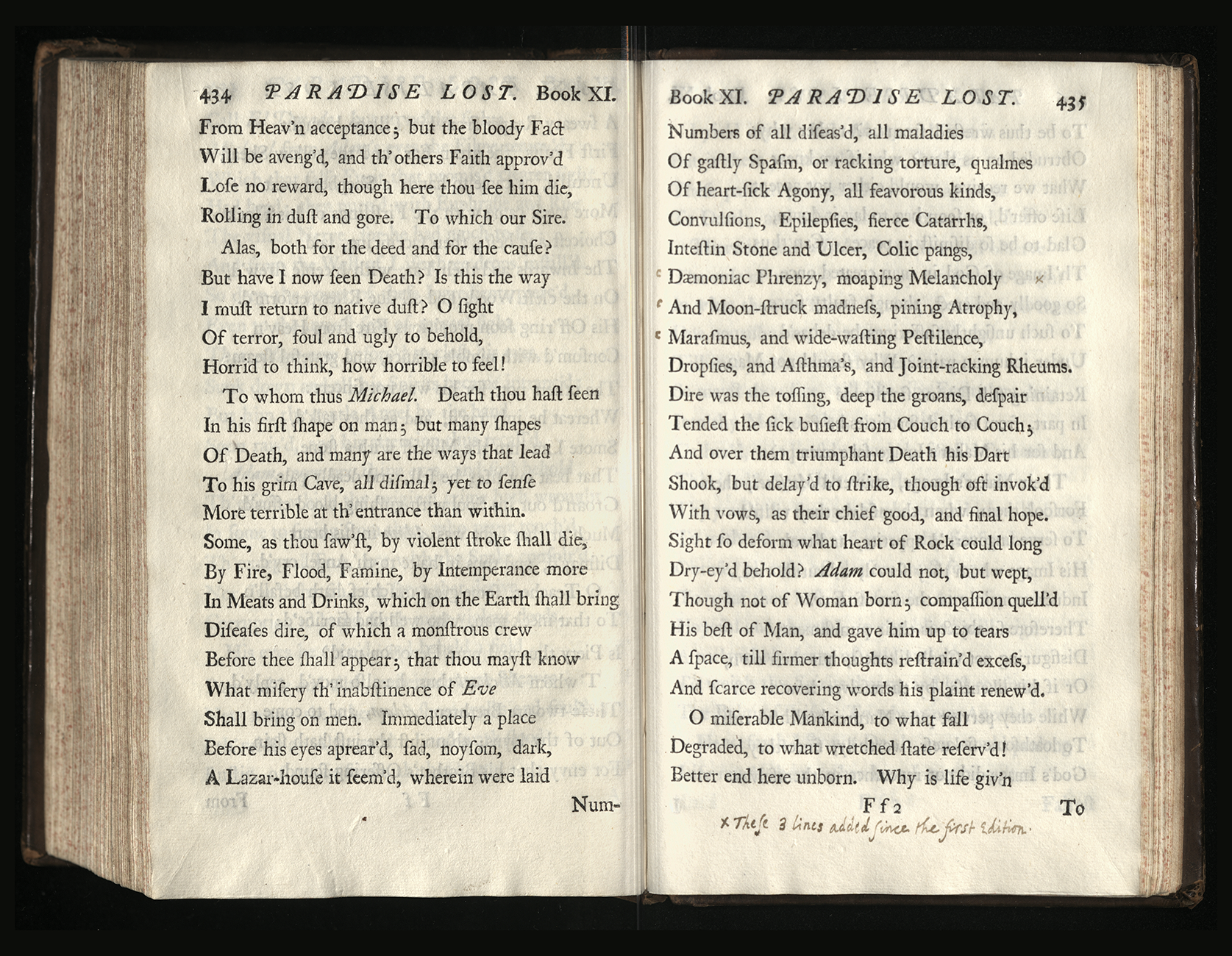

There are also signs of Pope collating the texts of his two copies of Paradise Lost and noting variants. Here, in the left-hand margin, he put inverted commas to mark lines of special significance. In the right-hand margin is a cross and, at the foot of the page, a note explaining that these lines were new to the twelve-book edition.

Pages from Paradise Lost: A Poem in Twelve Books, with annotations by Pope in the margins (Robinson 61).

Pages from Paradise Lost: A Poem in Twelve Books, with annotations by Pope in the margins (Robinson 61).

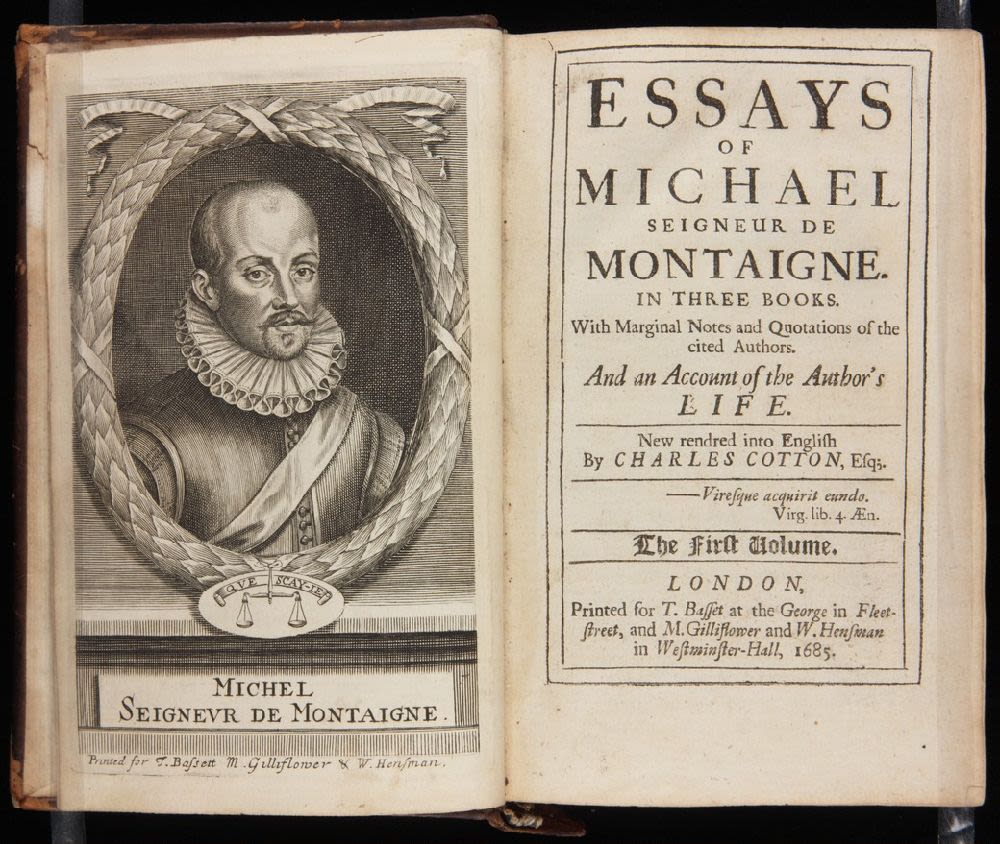

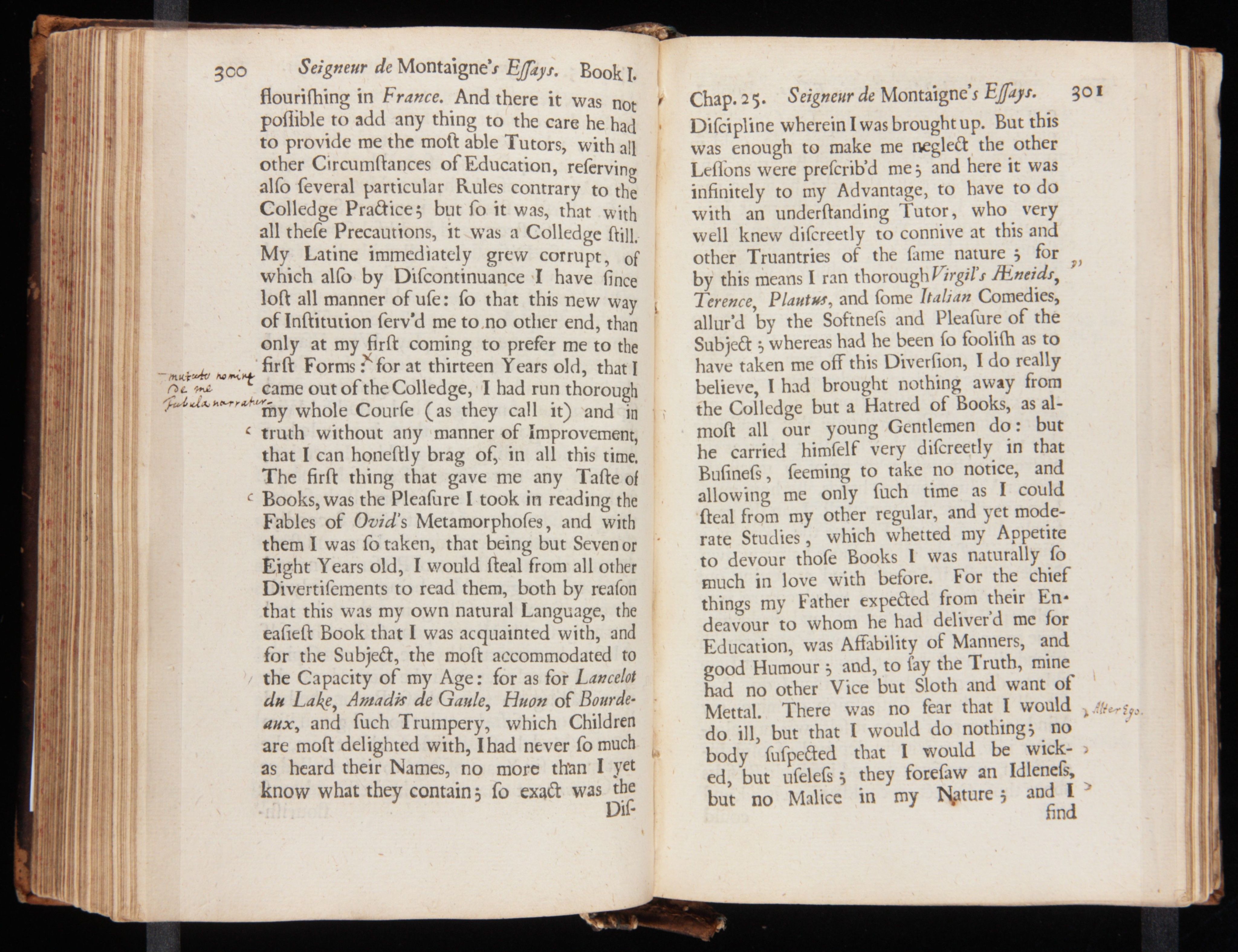

Pope did more than just collate texts. In 1706 he bought a second-hand copy of Charles Cotton’s translation of Montaigne’s Essays for three shillings.

Title page from Essays of Michael, Seigneur de Montaigne: in three books, by Charles Cotton and Michel de Montaigne (1685-86), available from Yale University Library online.

Title page from Essays of Michael, Seigneur de Montaigne: in three books, by Charles Cotton and Michel de Montaigne (1685-86), available from Yale University Library online.

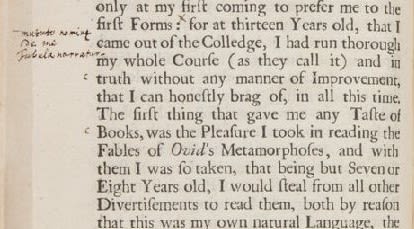

In the text of this book we can see Pope using the same crosses and commas to mark out important passages of text and adding his own commentary in the margins.

Extract from Essays of Michael, Seigneur de Montaigne: in three books. Written in the margins in Pope's handwriting, he has added his own commentary about the text, available from Yale University Library online.

Extract from Essays of Michael, Seigneur de Montaigne: in three books. Written in the margins in Pope's handwriting, he has added his own commentary about the text, available from Yale University Library online.

Books as Gifts

Throughout his life, Pope prided himself on his capacity for friendship. Two of his dearest friends during his teens and twenties were his near-contemporaries Teresa and Martha Blount. The Blount sisters were born to old Catholic family at Mapledurham House in Oxfordshire, just fourteen miles from Pope’s childhood home. This portrait shows Teresa (right) and Martha (left) in 1716, at the ages of twenty-eight and twenty-six respectively. As his fame grew, Pope displayed his affection for the sisters by presenting them with copies of his own writings.

Martha and Theresa Blount, Copyright © The Fitzwilliam Museum, Creative Commons License (BY-NC-ND)

Martha and Theresa Blount, Copyright © The Fitzwilliam Museum, Creative Commons License (BY-NC-ND)

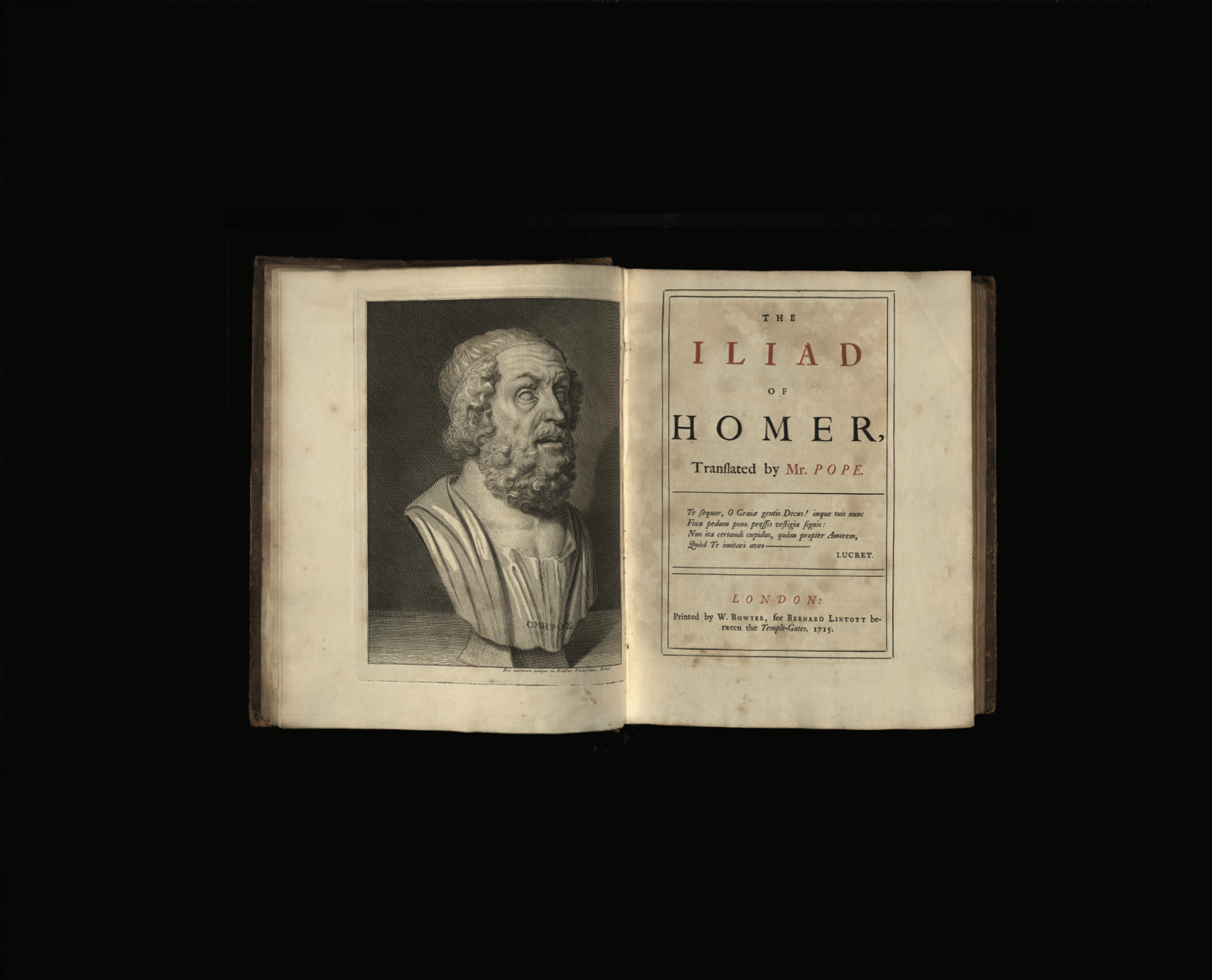

Here we see two such books that Pope presented to the Blount sisters in 1715.

Front covers of The Temple of Fame (left) by Alexander Pope (1715) and The Iliad of Homer vol. I (right), by Alexander Pope (1715-20) (Philip and Marjorie Robinson Collection (Robinson 70 and Robinson 60).

Front covers of The Temple of Fame (left) by Alexander Pope (1715) and The Iliad of Homer vol. I (right), by Alexander Pope (1715-20) (Philip and Marjorie Robinson Collection (Robinson 70 and Robinson 60).

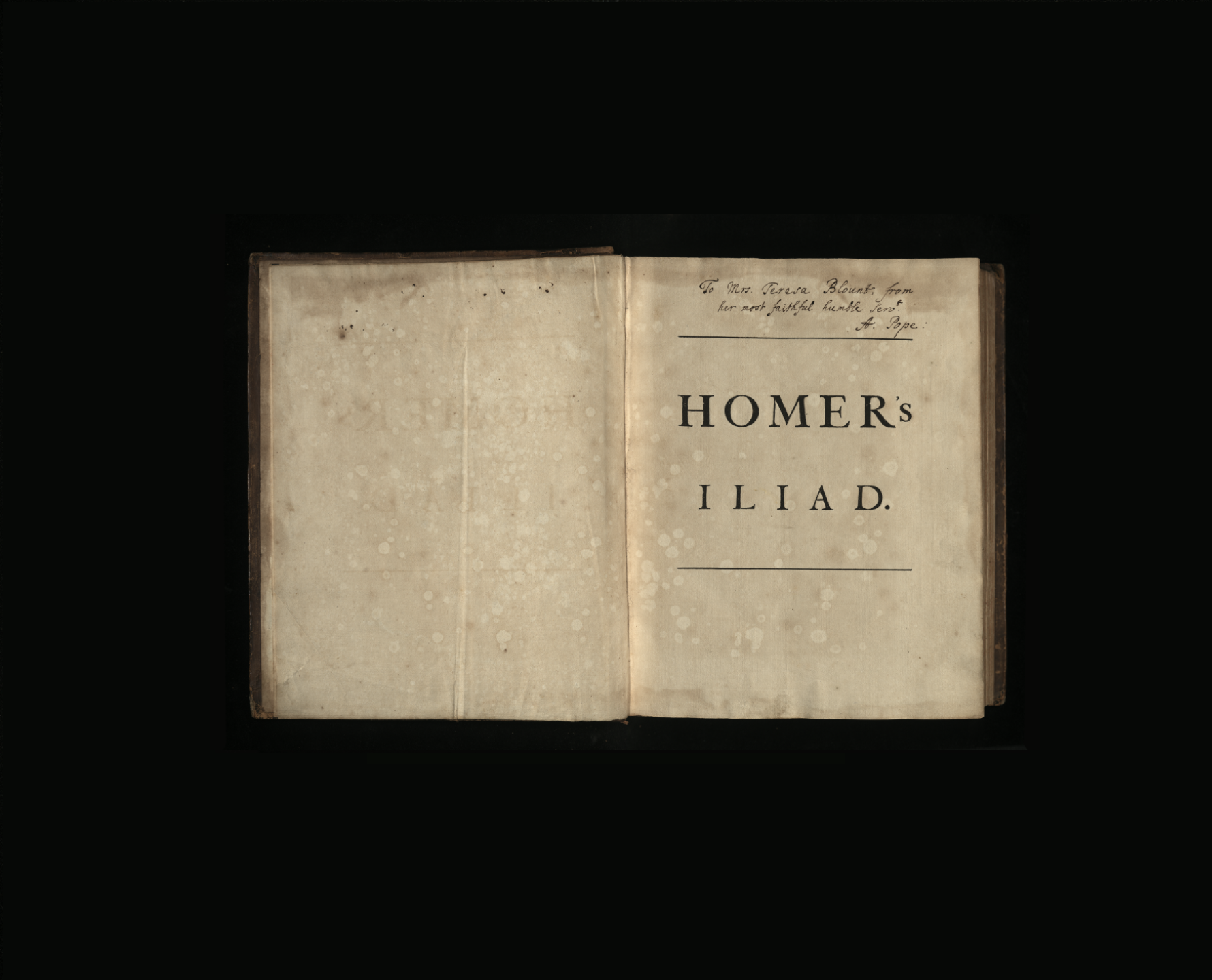

The one shown on the right in the above image, is a copy of the book that made Pope’s fortune: the first instalment in his six-volume translation of Homer’s Iliad, published in 1715. This deluxe copy is one of 750 printed on extra-thick paper in a large quarto format. The book is a masterpiece of design. According to the contract with his publisher, Bernard Lintot, Pope supervised the production of bespoke illustrated headpieces and tailpieces to adorn each section of the translation. A new font of type was specially cut to print the book.

At the top of the half-title in this copy is an inscription in Pope’s neat italic hand:

‘To Mrs. Teresa Blount, from | her most faithful humble serv.t | A. Pope’.

It is a stiff, formal inscription, in keeping with the grand volume in which it appears. See below for more details from The Iliad of Homer.

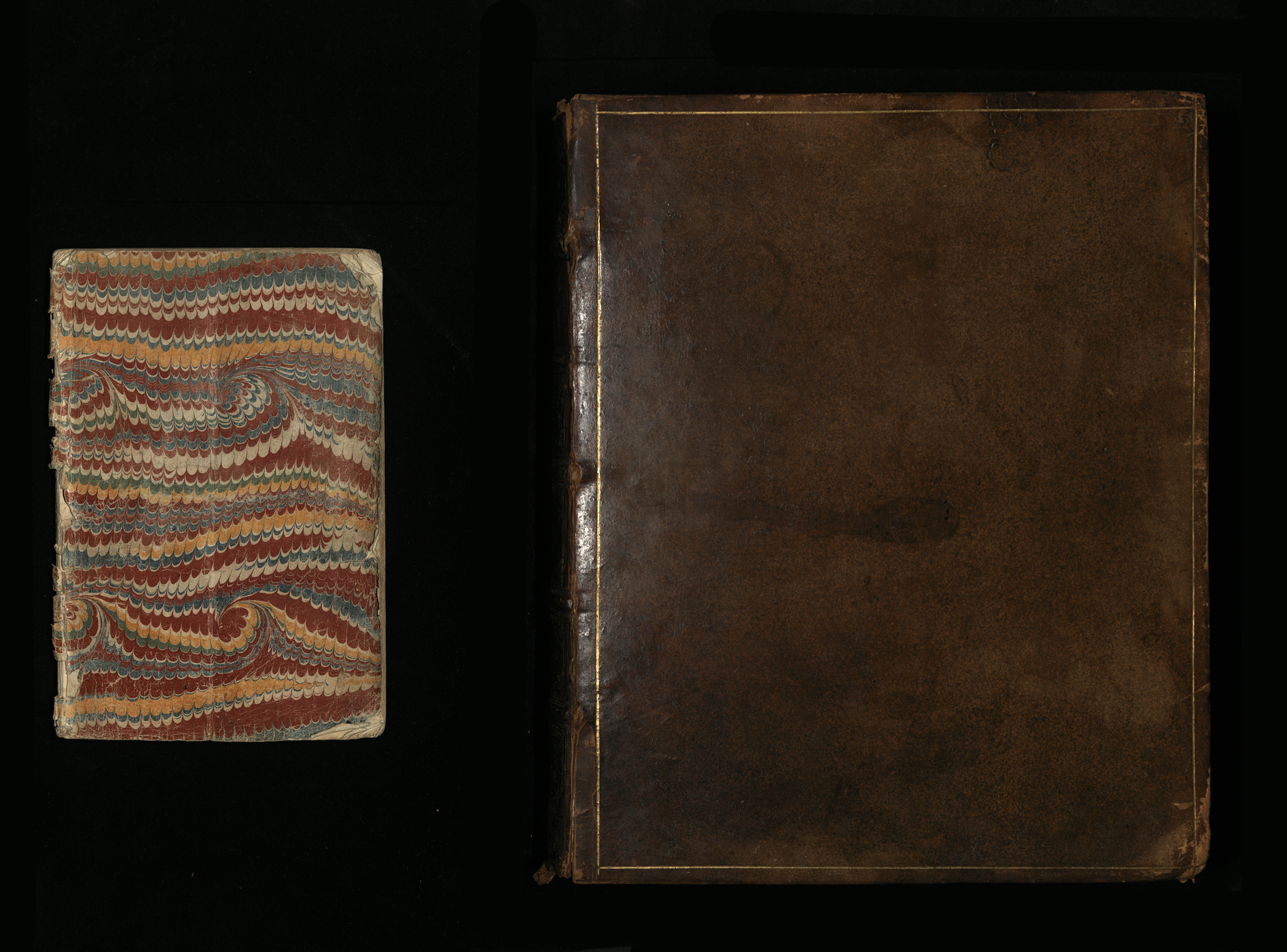

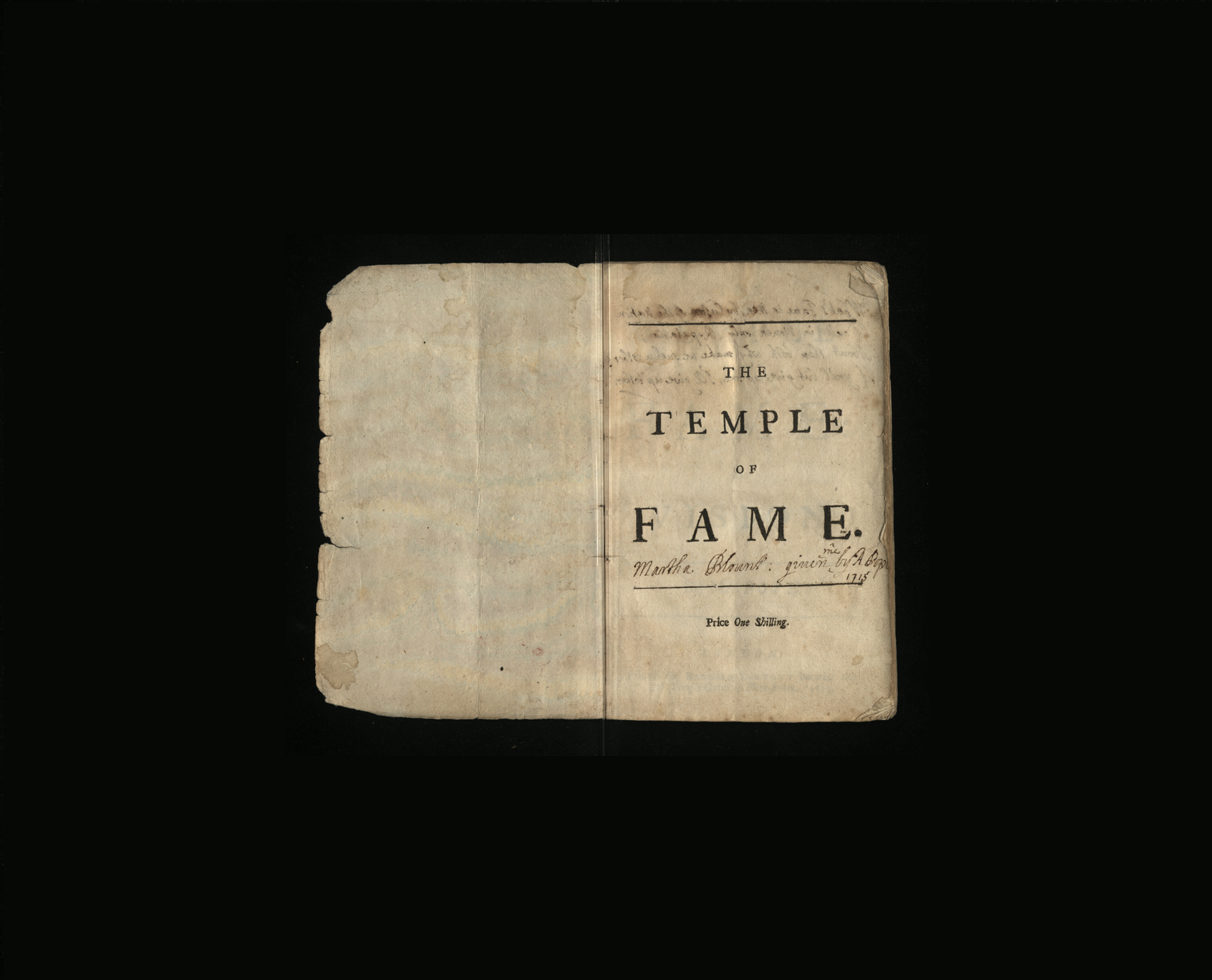

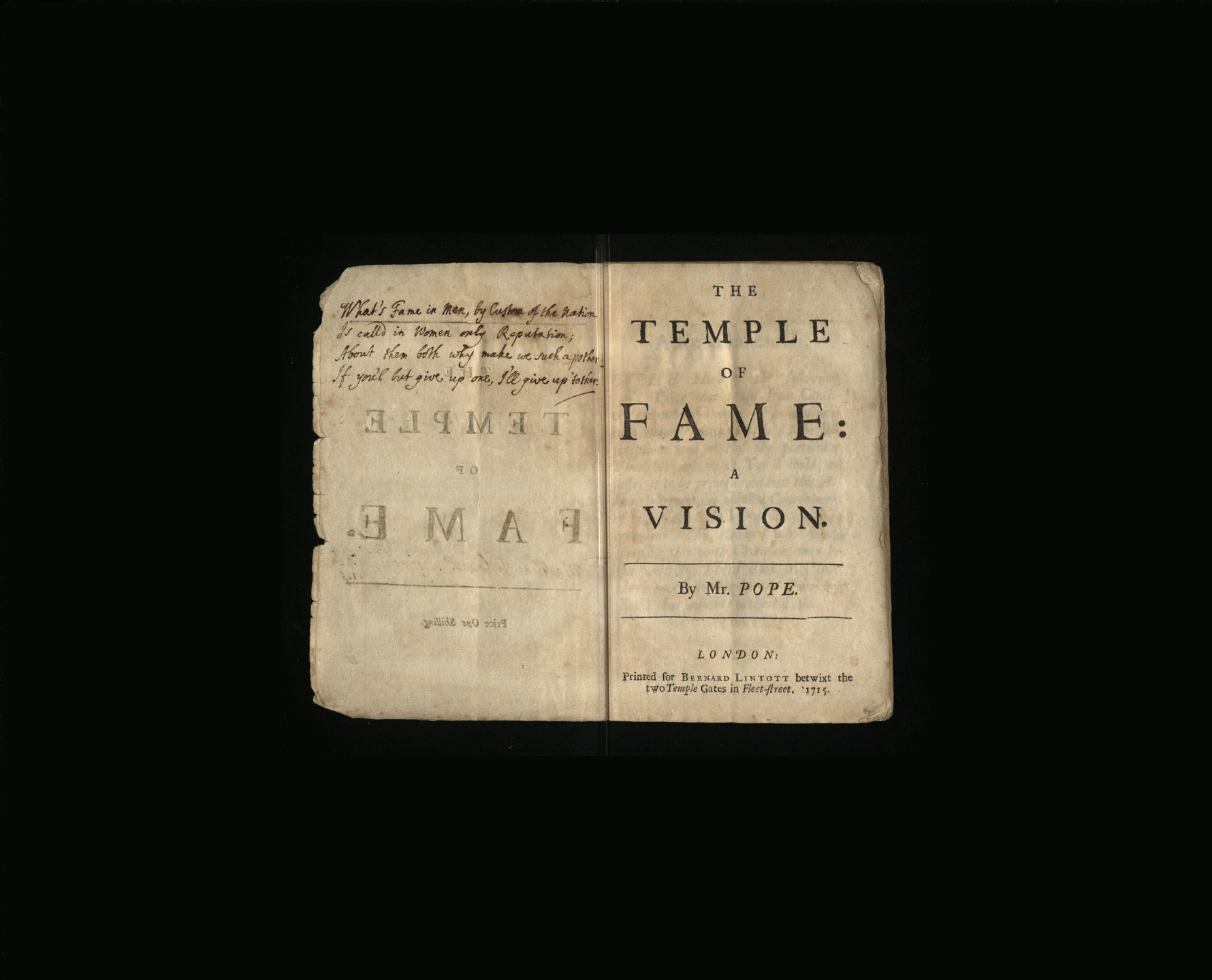

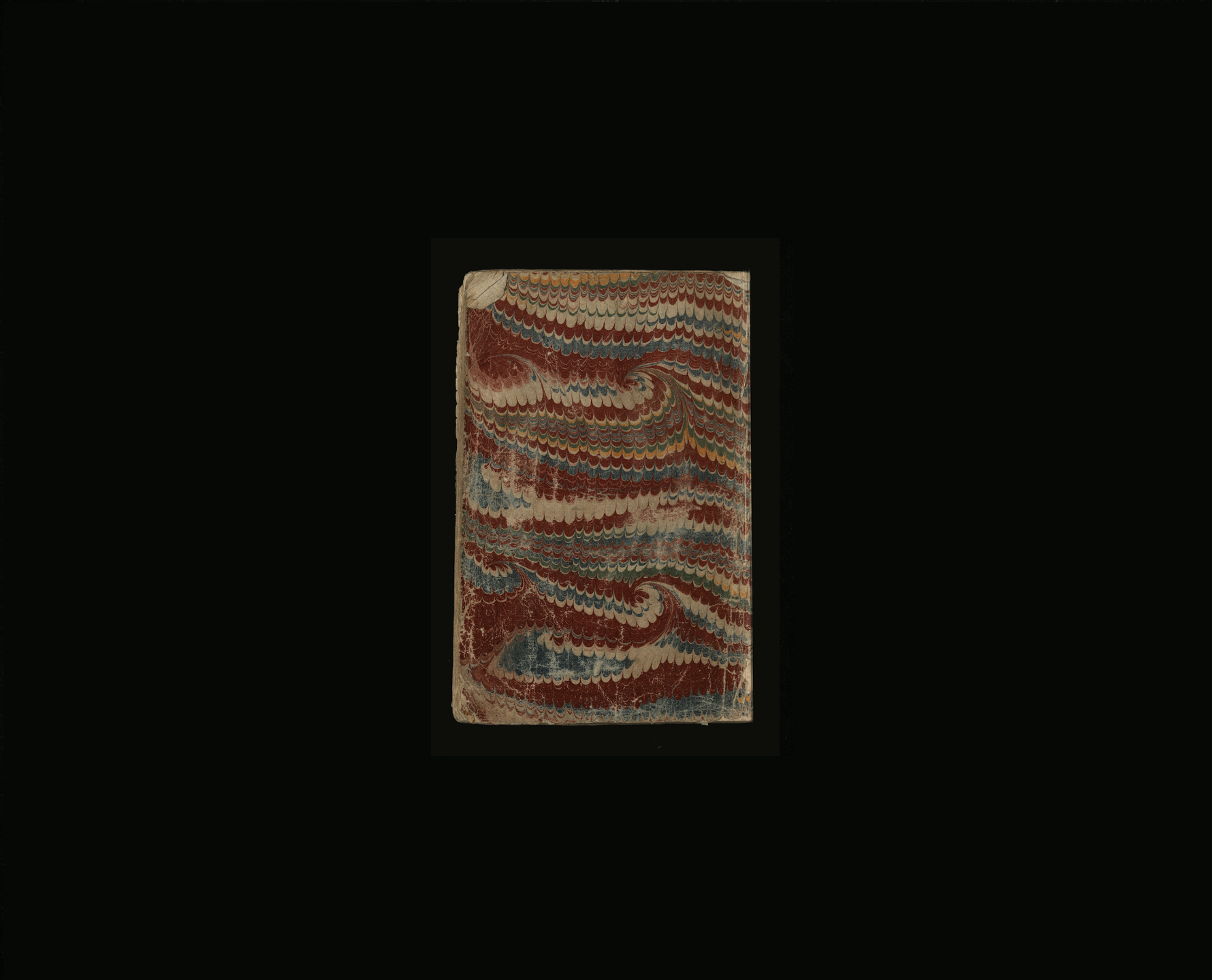

The second book, pictured on the left, is much smaller. This is a first edition of Pope’s poem The Temple of Fame, also published in 1715. Remarkably, this copy has remained unbound and is still stitched in its original marbled wrappers. On the half-title, Martha Blount has recorded in her own handwriting that the book was given to her by Pope. On the other side of the page is a four-line poem written by Pope in his most casual hand:

What’s Fame in Men, by Custom of the Nation

Is calld in Women only Reputation;

About them both why make we such a pother?

If you’l but give up one, I’ll give up ’tother.

The poem addresses Martha directly: it suggests that if she will give up her ‘reputation’ then Pope would gladly surrender his own ‘fame’. If one looks closely, one can detect creases where the book has been folded into quarters, perhaps to be slipped into a pocket.

Whereas the copy of the Iliad inscribed to Teresa is grand and imposing, this book inscribed to Martha is intimate. The relationship between Pope and Martha Blount remains enigmatic. We do not know if their partnership was strictly platonic or ever became romantic. But their correspondence makes clear the deep emotional bond that existed between the pair. This inscribed book provides a unique glimpse into that elusive relationship. See below for more details of The Temple of Fame.

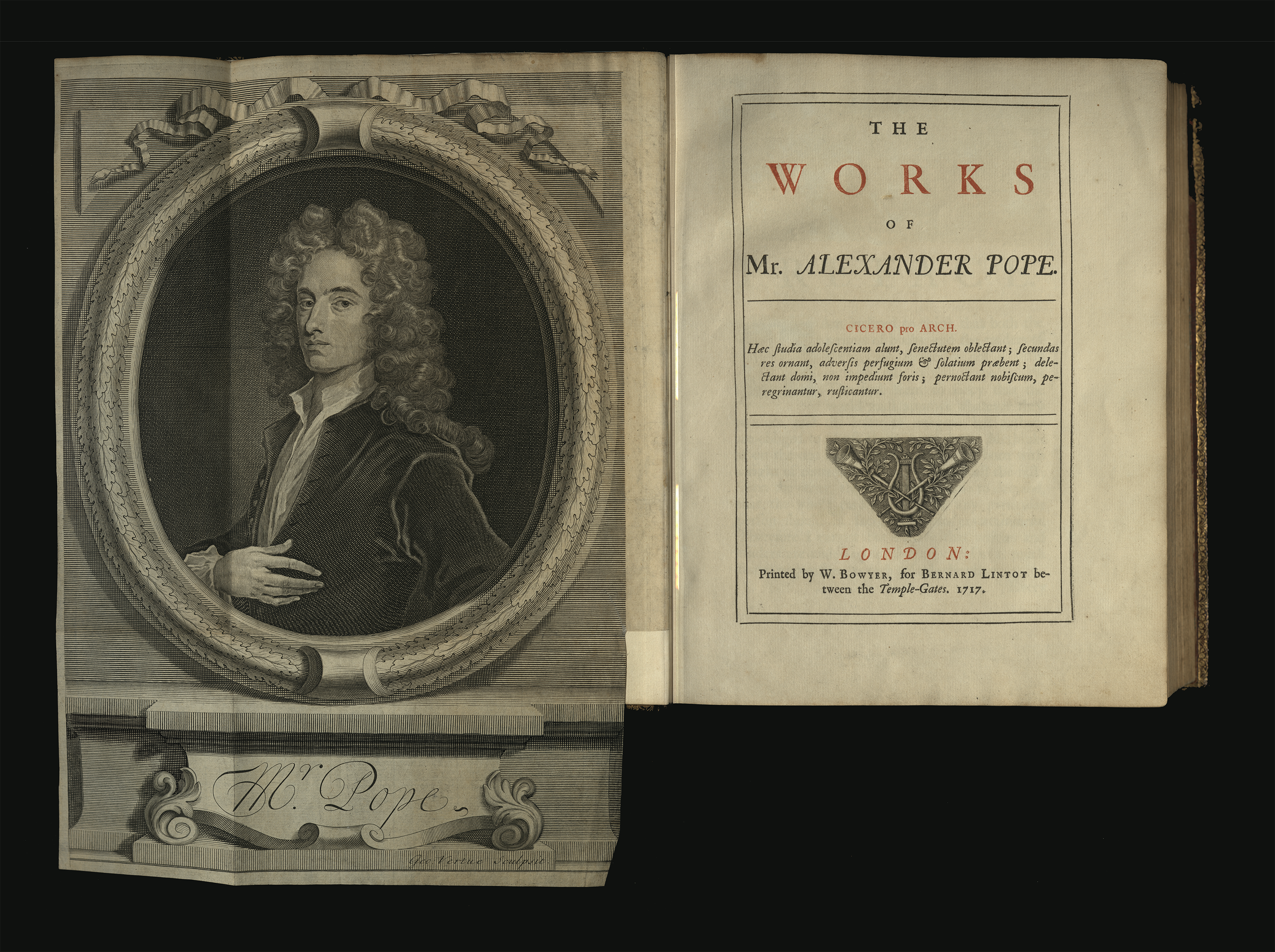

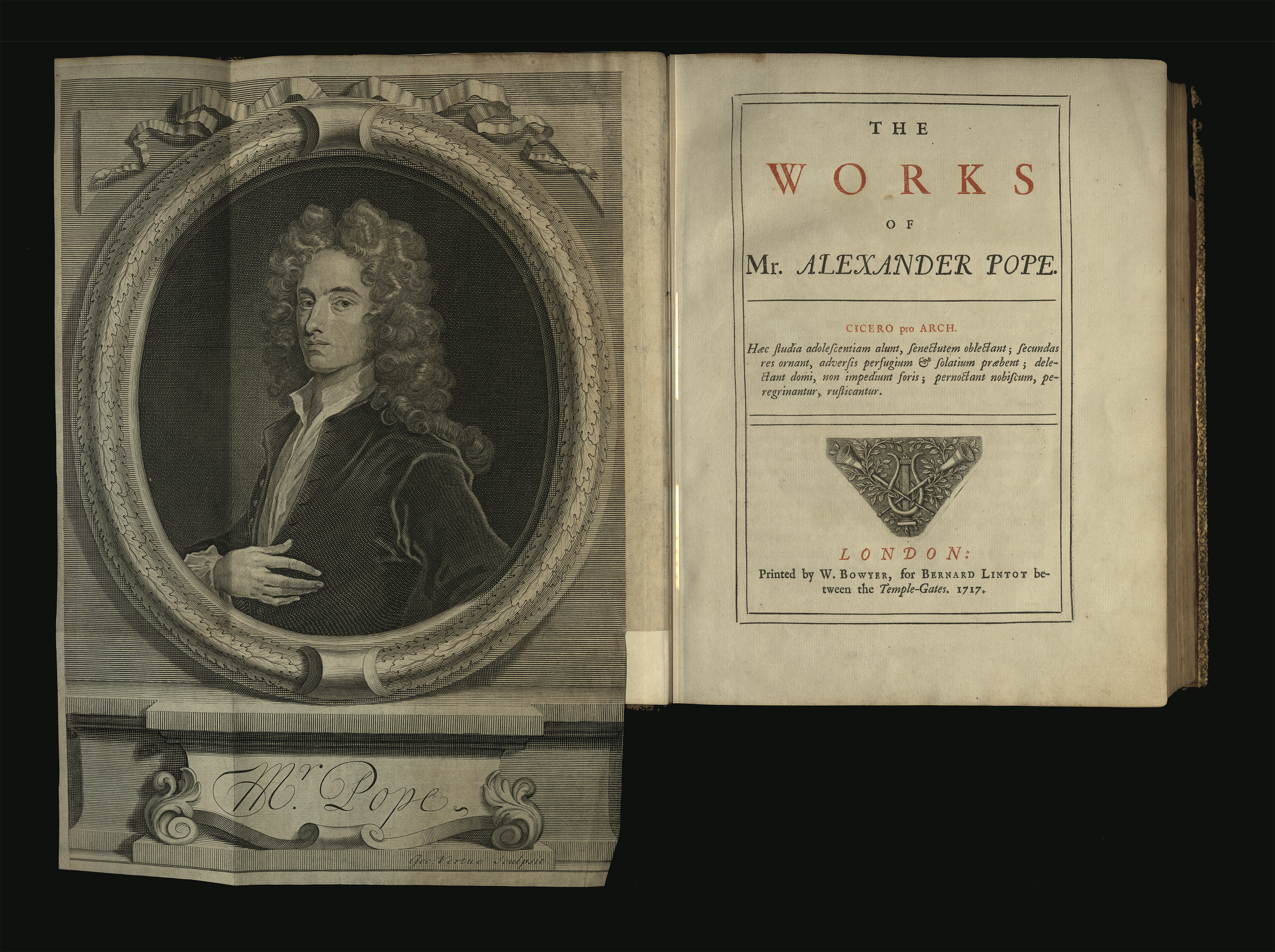

In 1717, at the age of twenty-nine, Pope published his collected works. He used the same imposing large quarto format, typeface, and layout as for his translation of the Iliad. The implication was that Pope, like Homer, was already an author of classical stature—an audacious statement by a poet so young. Each major poem has its own illustrated headpiece. The title page is faced by a large portrait of Pope, which needs to be folded twice to fit within the binding.

Title page and unfolded portrait from The Works of Mr. Alexander Pope, vol. 1, Alexander Pope (1717). Philip and Marjorie Robinson Collection (Robinson 441)

Title page and unfolded portrait from The Works of Mr. Alexander Pope, vol. 1, Alexander Pope (1717). Philip and Marjorie Robinson Collection (Robinson 441)

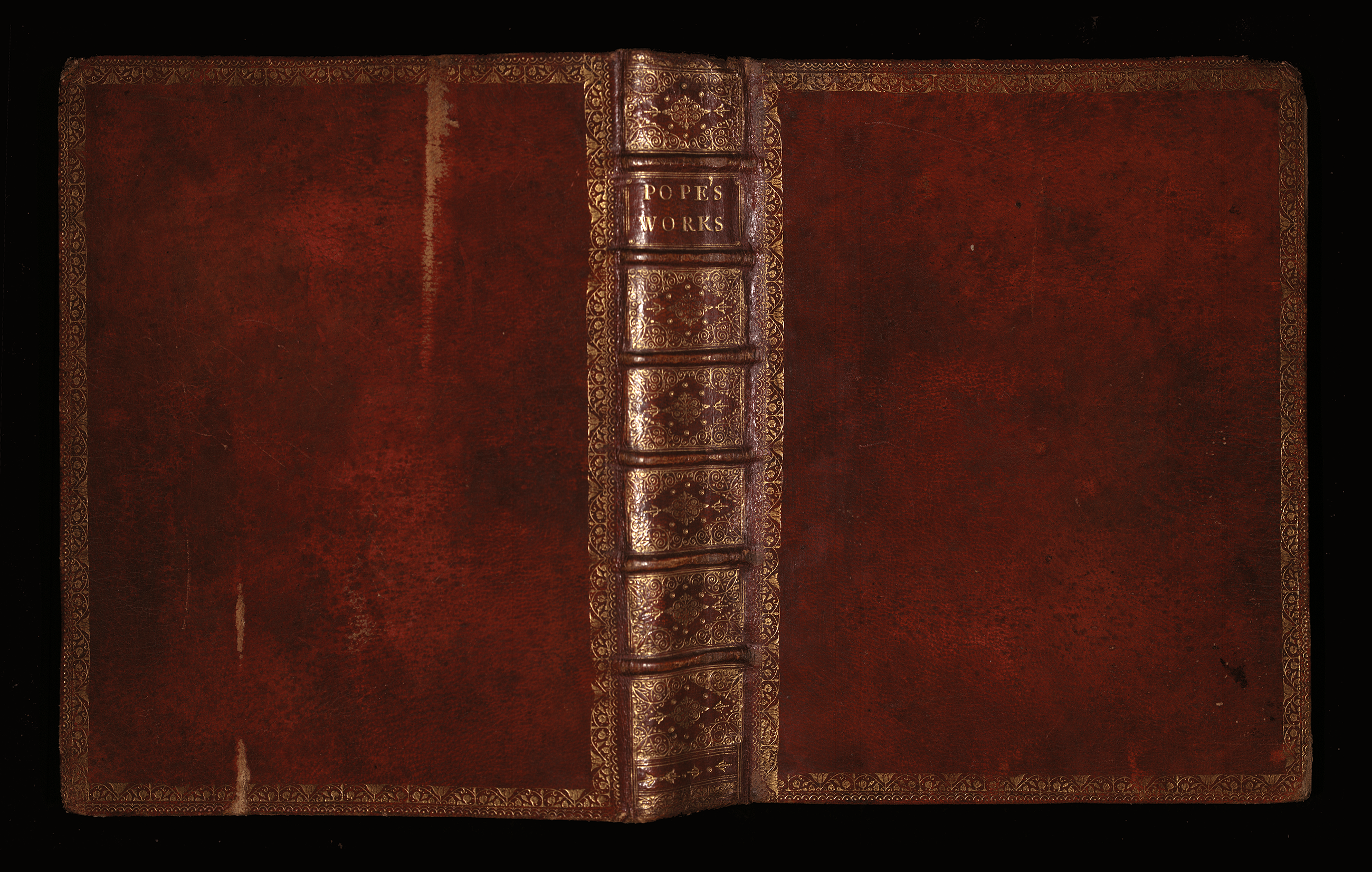

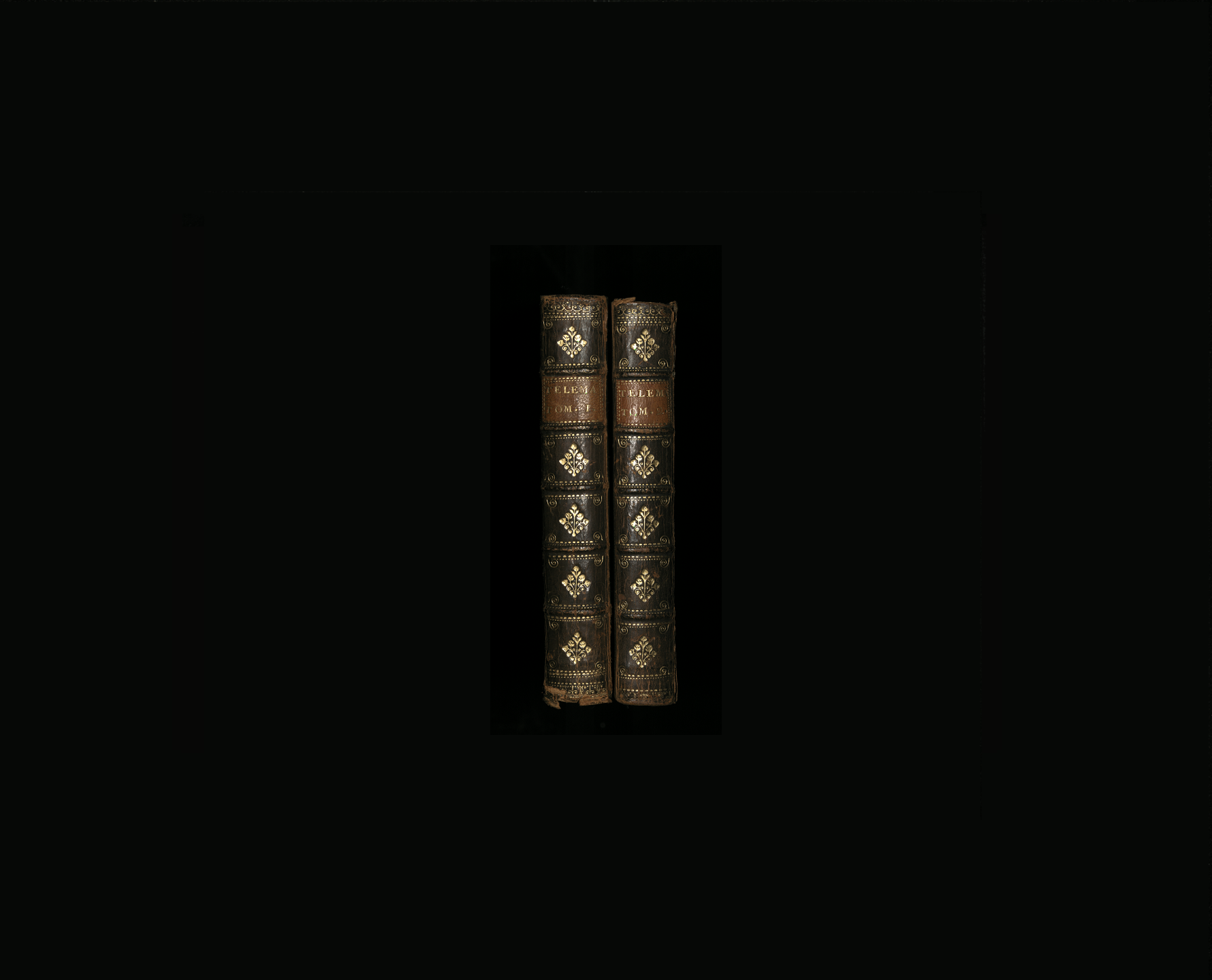

This copy is one of 120 printed on extra-thick royal paper. It is lavishly bound in crimson morocco leather, stamped with gilt detailing. The book was presented by Pope to Teresa Blount, though it does not have his inscription. However, it was almost certainly accompanied by a manuscript of the poem later published anonymously as ‘Verses Sent to Mrs. T. B. with His Works’.

Spine, front and back covers of The Works of Mr. Alexander Pope, vol. 1, by Alexander Pope (1717) (Philip and Marjorie Robinson Collection, Robinson 441).

Spine, front and back covers of The Works of Mr. Alexander Pope, vol. 1, by Alexander Pope (1717) (Philip and Marjorie Robinson Collection, Robinson 441).

By 1717, Pope has fallen out with Teresa, whom he had come to believe superficial, vain, and cruel. The ‘Verses’ makes a specific joke about her response to the book’s extraordinary red and gold binding:

This Book, which, like its Author, You

By the bare Outside only knew,

(Whatever was in either Good,

Not look’d in, or, not understood)

Comes, as the Writer did too long,

To be about you, right or wrong;

Neglected on your Chair to lie,

Nor raise a Thought, nor draw an Eye;

In peevish Fits to have you say,

See there! you’re always in my Way!

Or, if your Slave you think to bless,

I like this Colour, I profess!

That Red is charming all will hold,

I ever lov’d it—next to Gold.

The poem balances broad wit with a cruel twist the knife, in the manner of much of Pope’s finer satirical verse. Teresa Blount is skewered both for her neglect of the poet and for her cupidity. According to the poem, the only reason she would keep the book is because she likes the plush binding.

Receiving Books

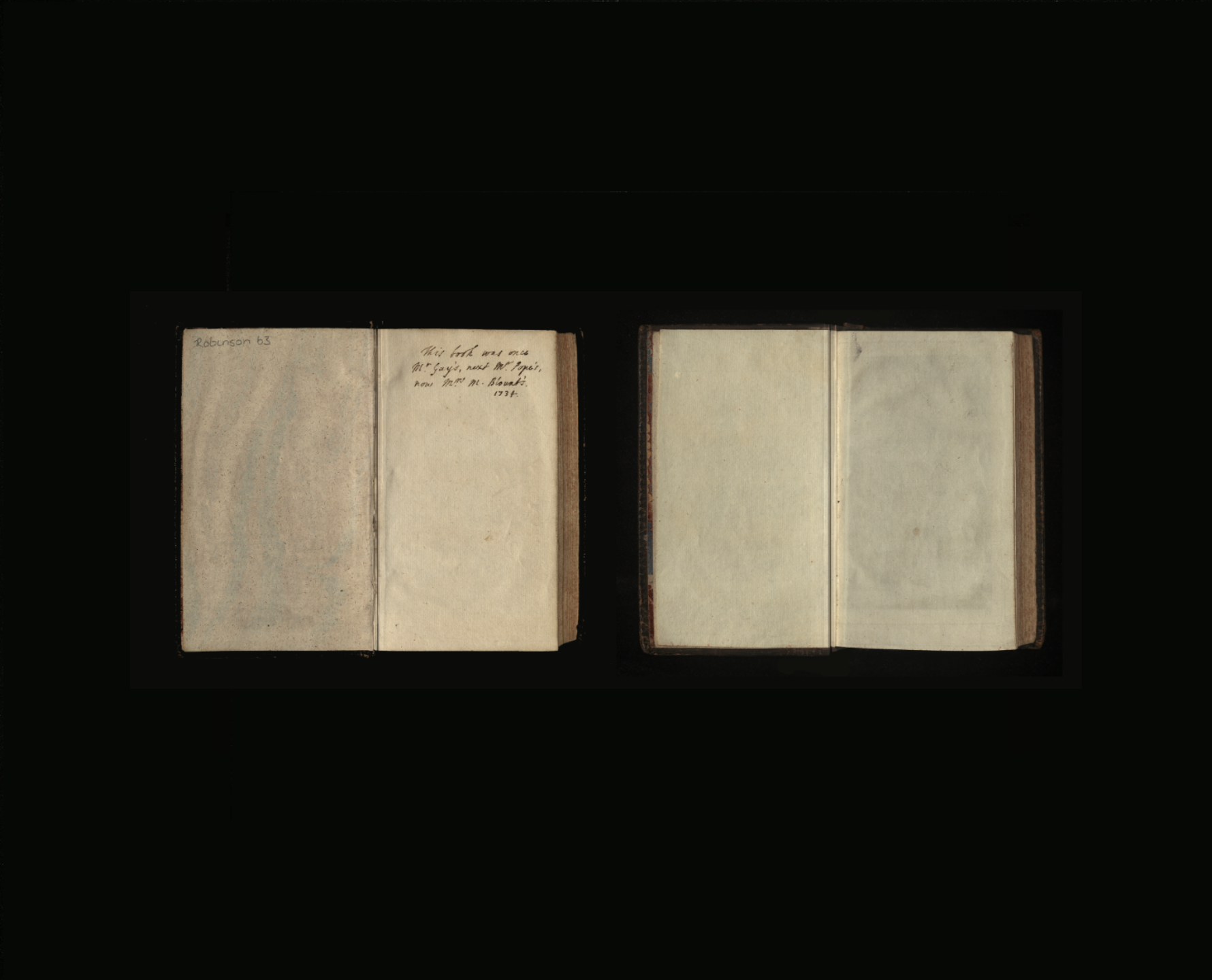

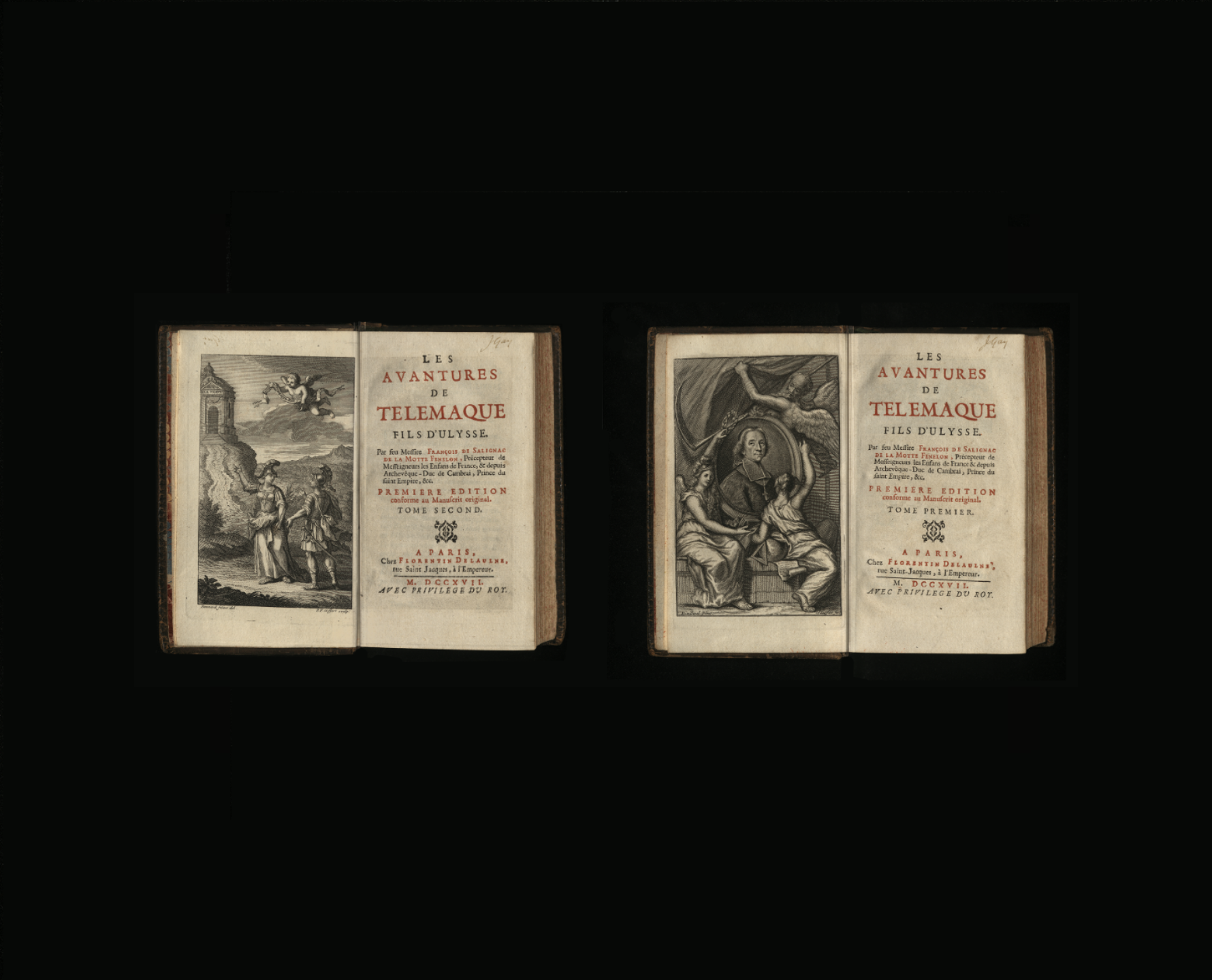

Pope did not only give books as tokens of friendship. He received them too. This copy of Archbishop Fénelon’s Telemachus originally belonged to the poet and dramatist John Gay, who, along with Pope, Jonathan Swift, John Arbuthnot, and Thomas Parnell was part of the ‘Scriblerus Club’ that met during the latter part of the reign of Queen Anne.

Gay inscribed his name on the title page. And then, at some point before Gay’s death in 1732, he gave the set to Pope who, in turn, later presented it to Martha Blount in 1734. Pope recorded the changing ownership at the top of the front flyleaf.

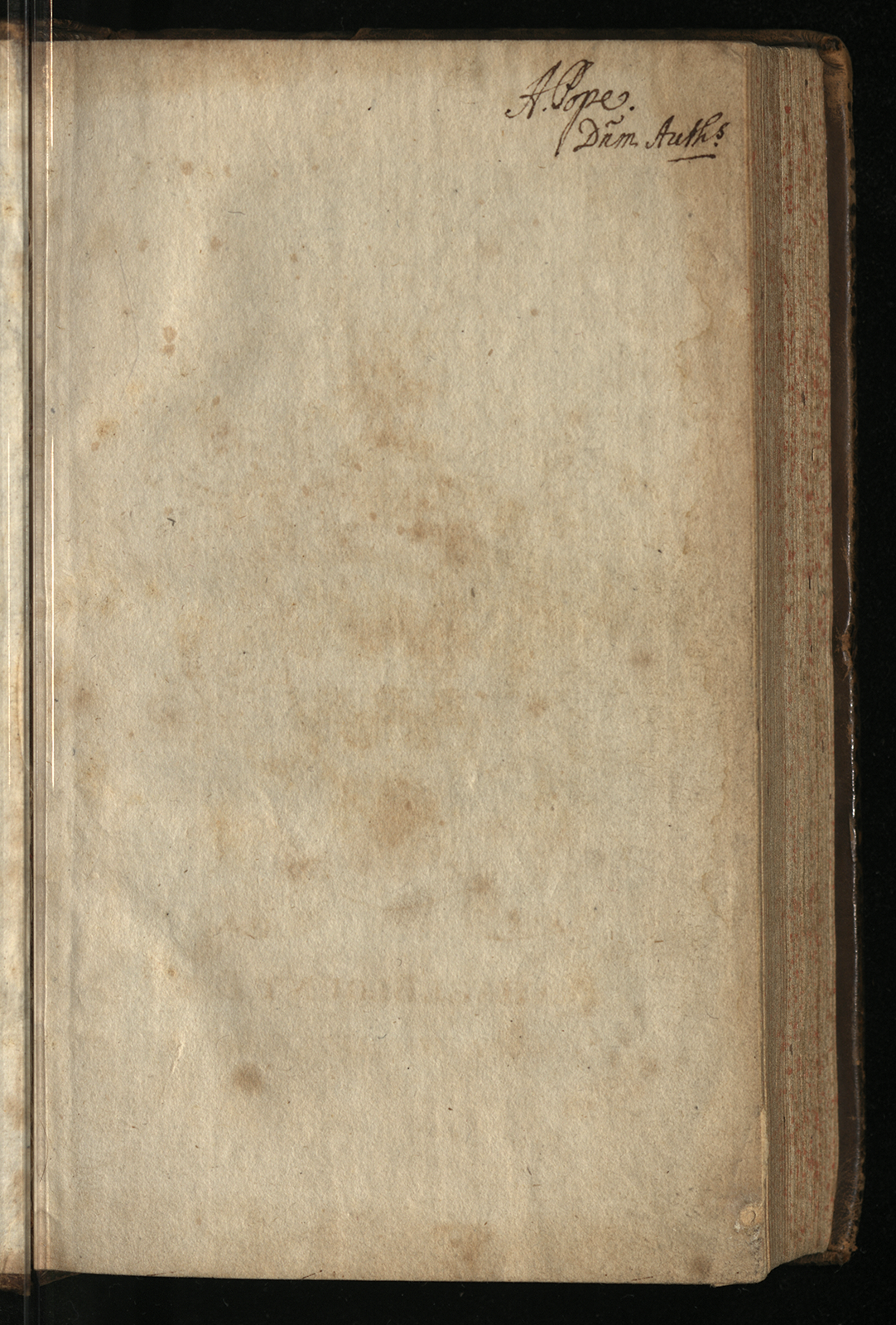

Pope was careful to record when a book had been given to him by another author. Here, in his copy of Matthew Prior’s Poems on Several Occasions, Pope has written ‘Dñm Auths’ for donum auctoris or ‘given by the author’.

Page from Poems on Several Occasions, showing Pope's inscription, by Matthew Prior (1721) (Philip and Marjorie Robinson Collection, Robinson 65).

Page from Poems on Several Occasions, showing Pope's inscription, by Matthew Prior (1721) (Philip and Marjorie Robinson Collection, Robinson 65).

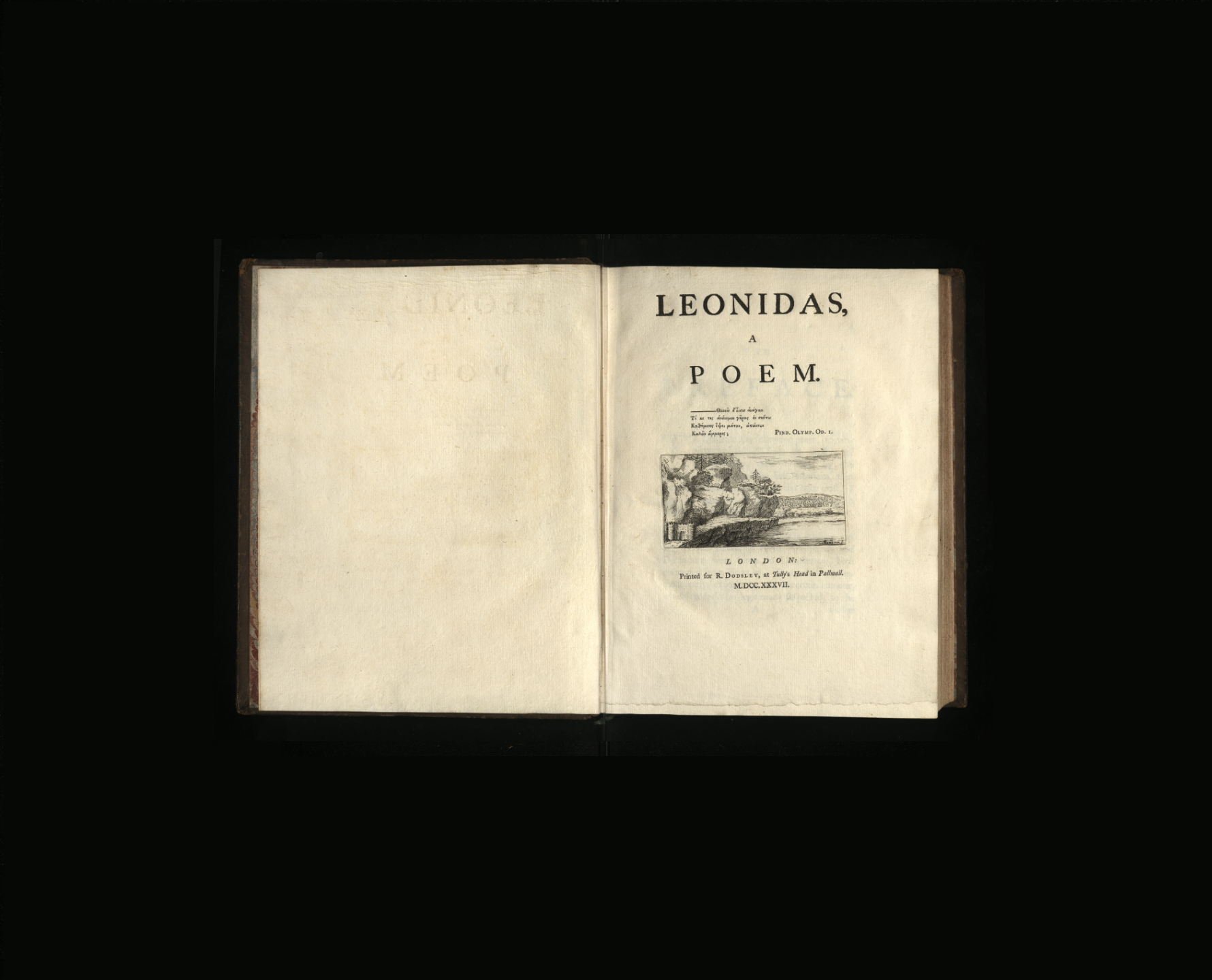

Similarly, this copy of Richard Glover’s historical epic poem, Leonidas, published in 1737 (below), has a note in Pope’s hand, stating that it was given to him by the author in the year of publication. It is a beautiful copy, bound in speckled calf with gilt stamping and vivid marbled endpapers.

The printing of Leonidas was evidently inspired by Pope’s earlier experiments in bibliographical design. Like the Iliad and the Works of 1717, it is a large format quarto with a limited run of deluxe copies printed on thick paper. This is one of the deluxe copies.

Provenance

Pope died in 1744, shortly after his sixty-sixth birthday. His will stipulated that Martha Blount should take sixty books from his library, in addition to granting her a thousand pounds and the residue of his estate. After Martha’s death in 1762, all her goods passed to her nephew, Michael Blount, and the books inherited from Pope passed into the family library at Mapledurham House in Oxfordshire.

In 1952 many of the books formerly belonging to or presented by Pope were purchased from the Mapledurham estate by the high-end London firm of William H. Robinson, run by the brothers Lionel and Philip Robinson.

Over the next twenty years, many of the Pope-Blount books were sold to libraries and private collectors in America, where they remain to this day. However, the Robinson brothers kept some of the most precious books for themselves. After Philip Robinson died in 1989, the remains of the collection passed to his wife, Marjorie Robinson, who bequeathed them to Newcastle University in 1998. They are now housed in Newcastle University Special Collections & Archives, in the Philip Robinson Library.

Photograph of a teaching session with material on display from Newcastle University Special Collections & Archives

Photograph of a teaching session with material on display from Newcastle University Special Collections & Archives

This digital exhibition is curated by Dr Joseph Hone, Lecturer in Literature and Book History at Newcastle University. You can find out more about these books in Dr Hone's recent article 'Pope and the Blounts: Books Formerly at Mapledurham House', The Library, 7th ser., 24 (2023), 343-70.'

Newcastle University Special Collections & Archives collects, preserves, promotes and provides access to unique and distinctive books and archives. These resources are made available not only to our own University staff and students, but to researchers from other institutions and to the wider community.

To find out more about our holdings please browse at our Collections Guide. To discover how you can consult materials see Use our Collections.