Big Things in Small Packages:

An Exhibition of Miniature Books

How we define miniature books has changed over time such that, in 1983, the Miniature Book Society was founded in the U.S.A. with the aim of standardising their size. Today, a book is generally classified as ‘miniature’ if none of its dimensions (length, width, depth) exceed 7.5 centimetres (3 inches).

This exhibition draws upon miniature, and small books and manuscripts held in Newcastle University Library’s Special Collections and Archives. It explores the types of materials that were created in miniature form, and the different motivations for creating such miniscule objects.

Curated by Robinson Bequest Student Kiah Edwards. The miniature books by James Lamar Weygand were kindly loaned to the exhibition by Charles Bell.

A Small Obsession

Book formats (such as folio, quarto, octavo and duodecimo) are determined by how many times the printed sheet of paper has been folded and the resulting size of the book’s leaves after they have been trimmed. Traditionally, folios were the format reserved for library books and octavos were the format used for portable books, such as devotional works. Octavos also became the dominant format after 1700.

So, if a book’s format and size is linked to its purpose and intended audience, what of miniature books? Are they merely curiosities? Does the only interest in miniature books rest in their size? Or is there more to them than novelty?

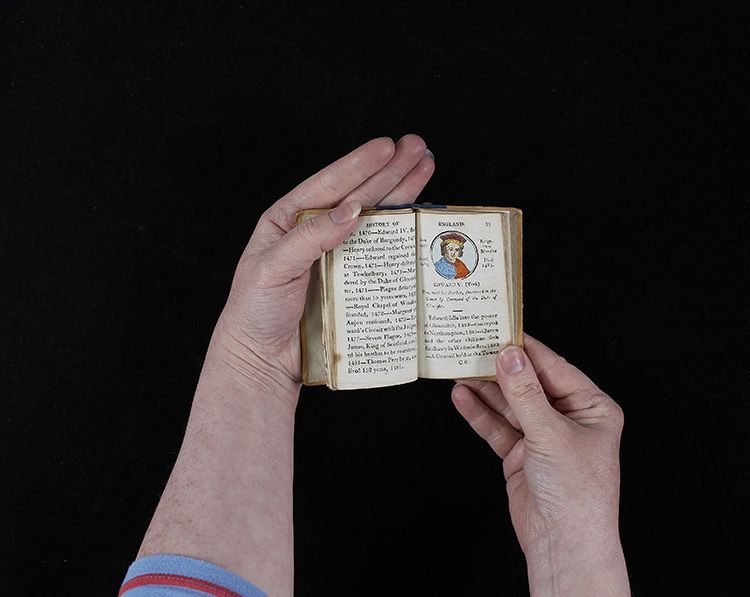

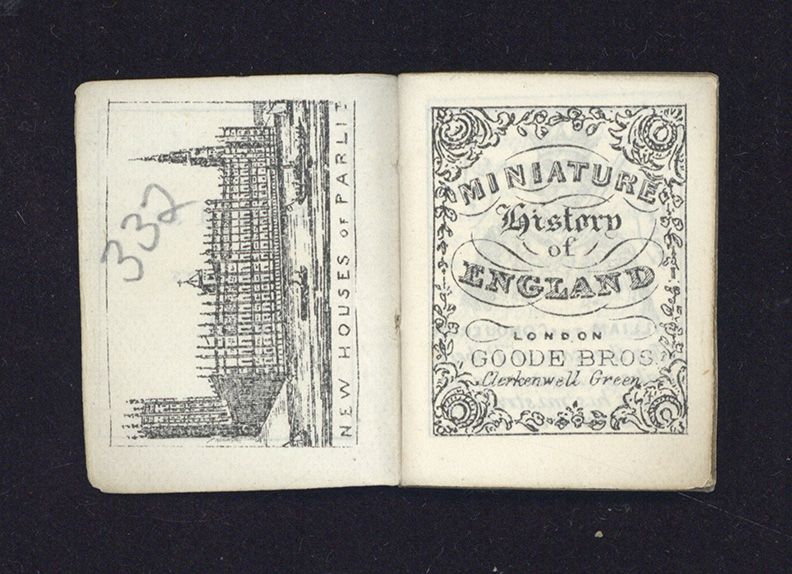

Miniature books are often no taller than 7.5cm (3 inches), as seen here in Miniature History of England.

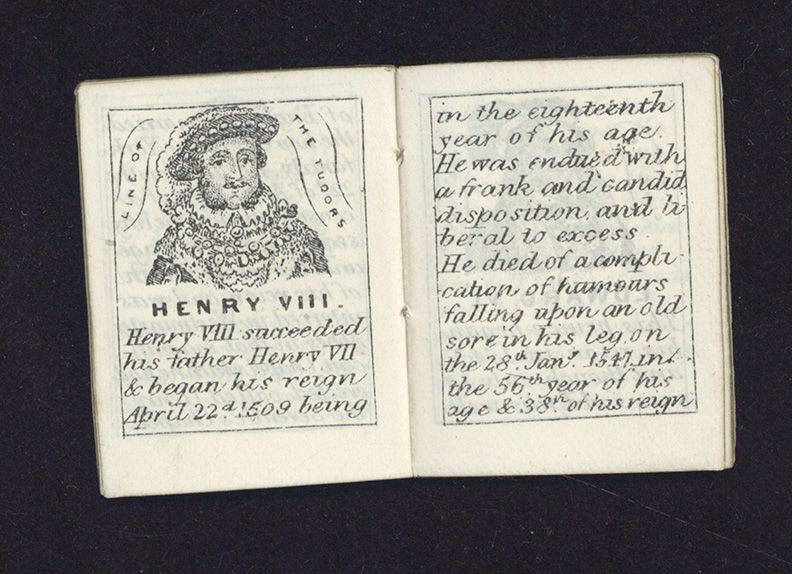

Miniature History of England: from William the Conqueror to Queen Victoria

(London: Goode Bros., c.1870)

19th C. Coll. 942 HIS, 19th Century Collection

Vademecums: ‘Go With Me’ Reference Books

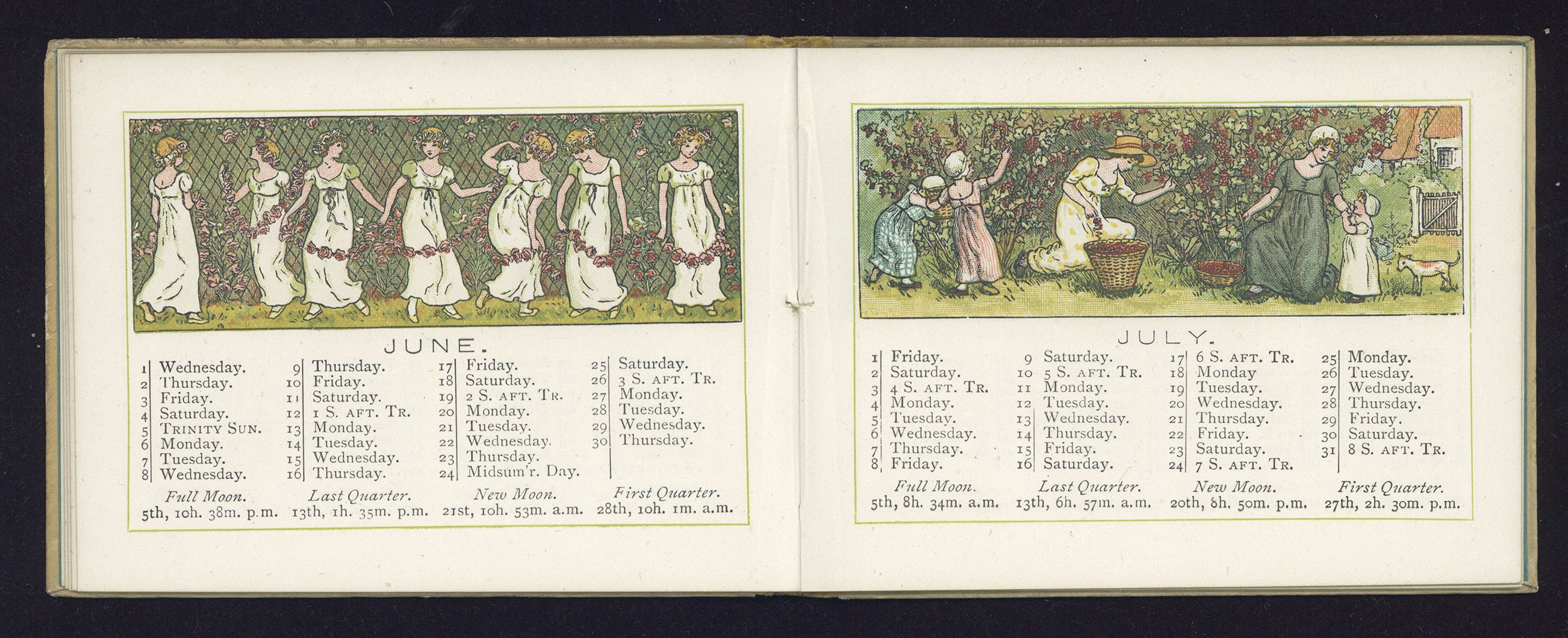

One of the reasons why a book might be printed in miniature is its portability: miniature and small books can be carried in pockets for quick reference and constant company. During the Middle Ages, most miniature books were devotional works (prayer books, psalters, books of hours and Bibles) carried by a chain attached to the wearer’s belt or girdle. Miniature almanacs and calendars appeared in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries, sometimes carried in purpose-made bags. By the Nineteenth Century, the range of miniature books expanded to include more books intended for use in everyday life.

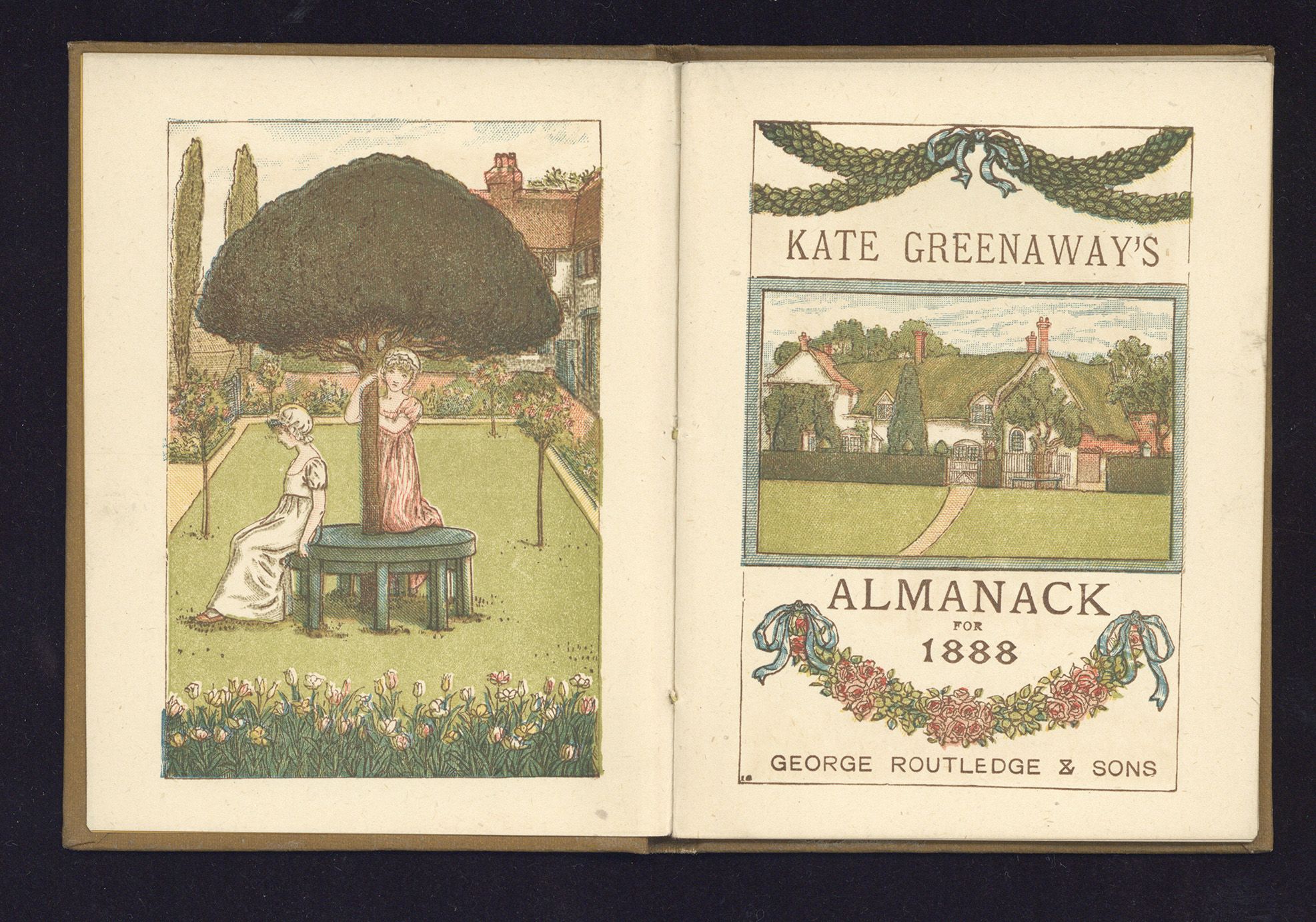

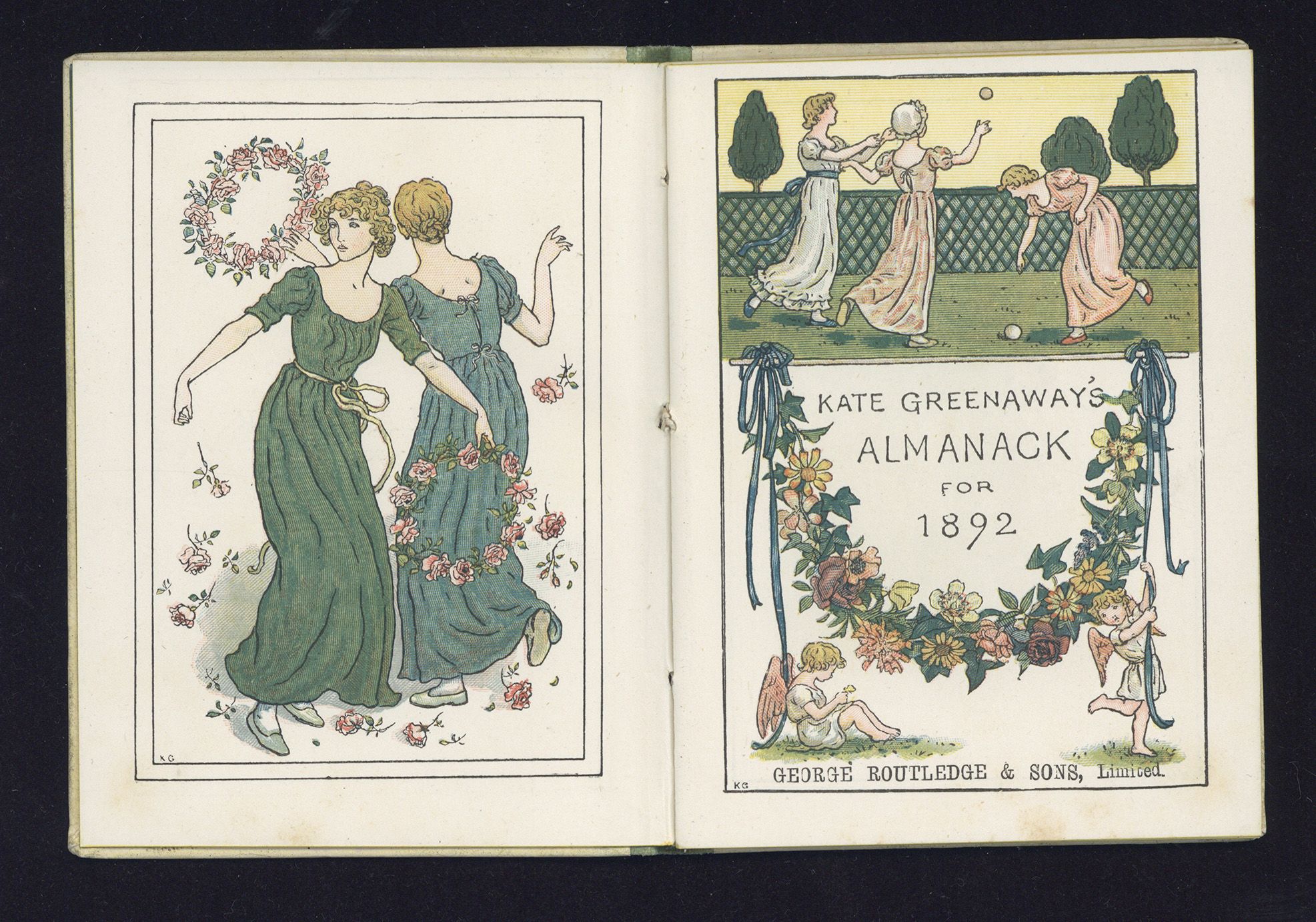

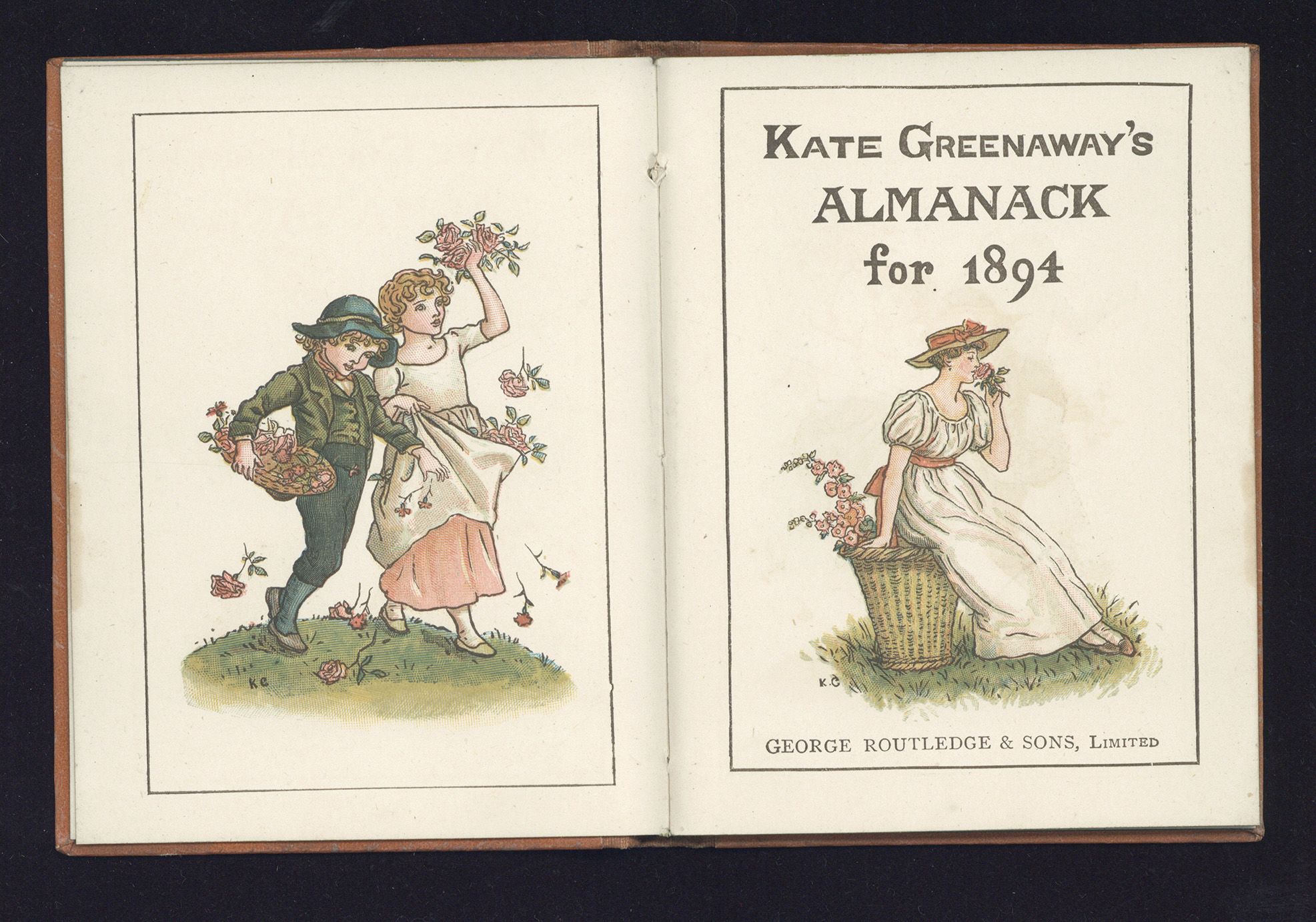

Here you see a selection of almanacs produced by Kate Greenaway (1846-1901). Greenaway could be said to have been the most significant female illustrator of the Victorian era and her almanac series was one of her best-known publications. They are illustrated calendars which were published at one shilling (approximately £3.30 today).

Greenaway, Kate. Almanacks for 1887, 1888, 1892 and 1894

(London: G. Routledge, 1887)

19th C. Coll. 030 GRE, 19th Century Collection

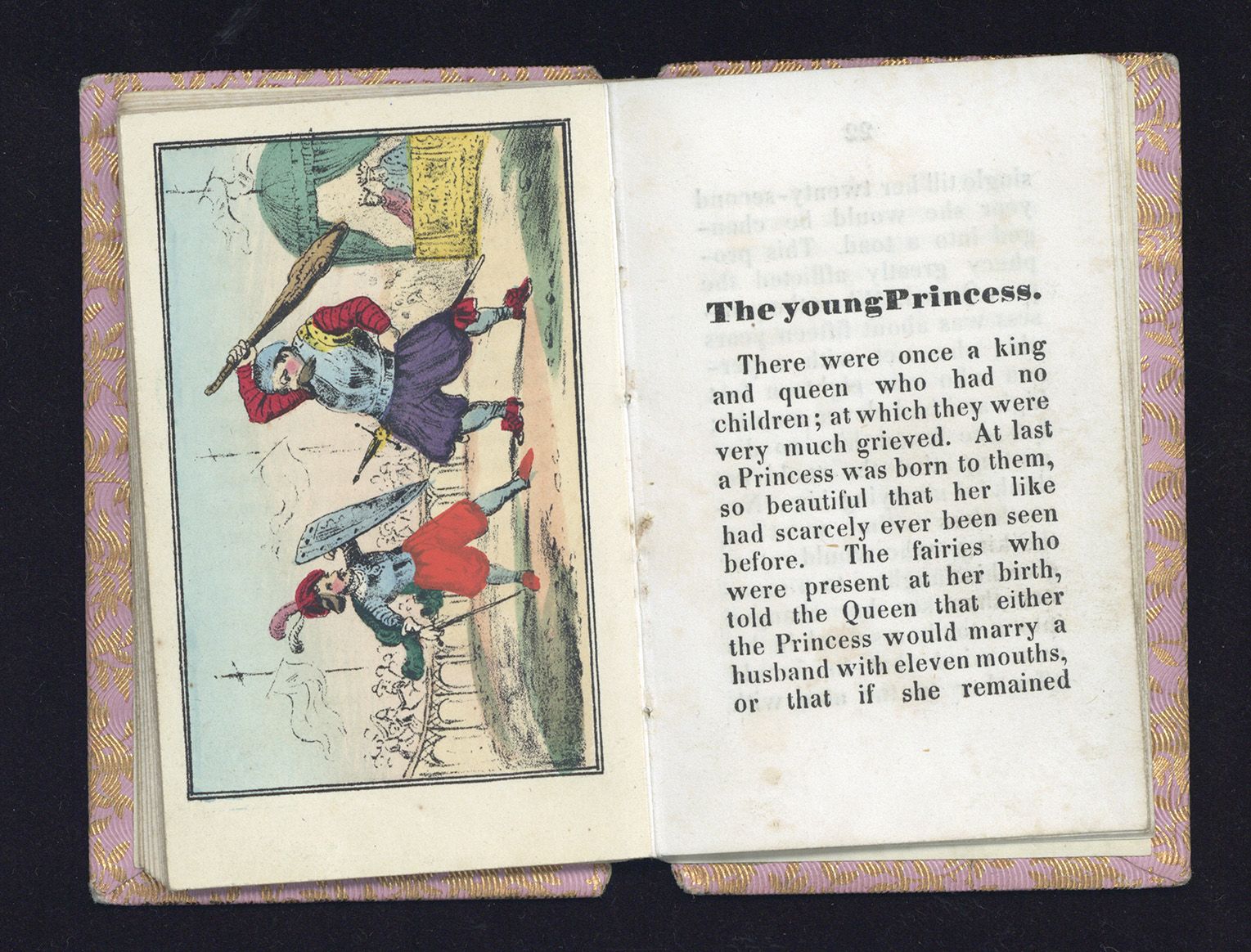

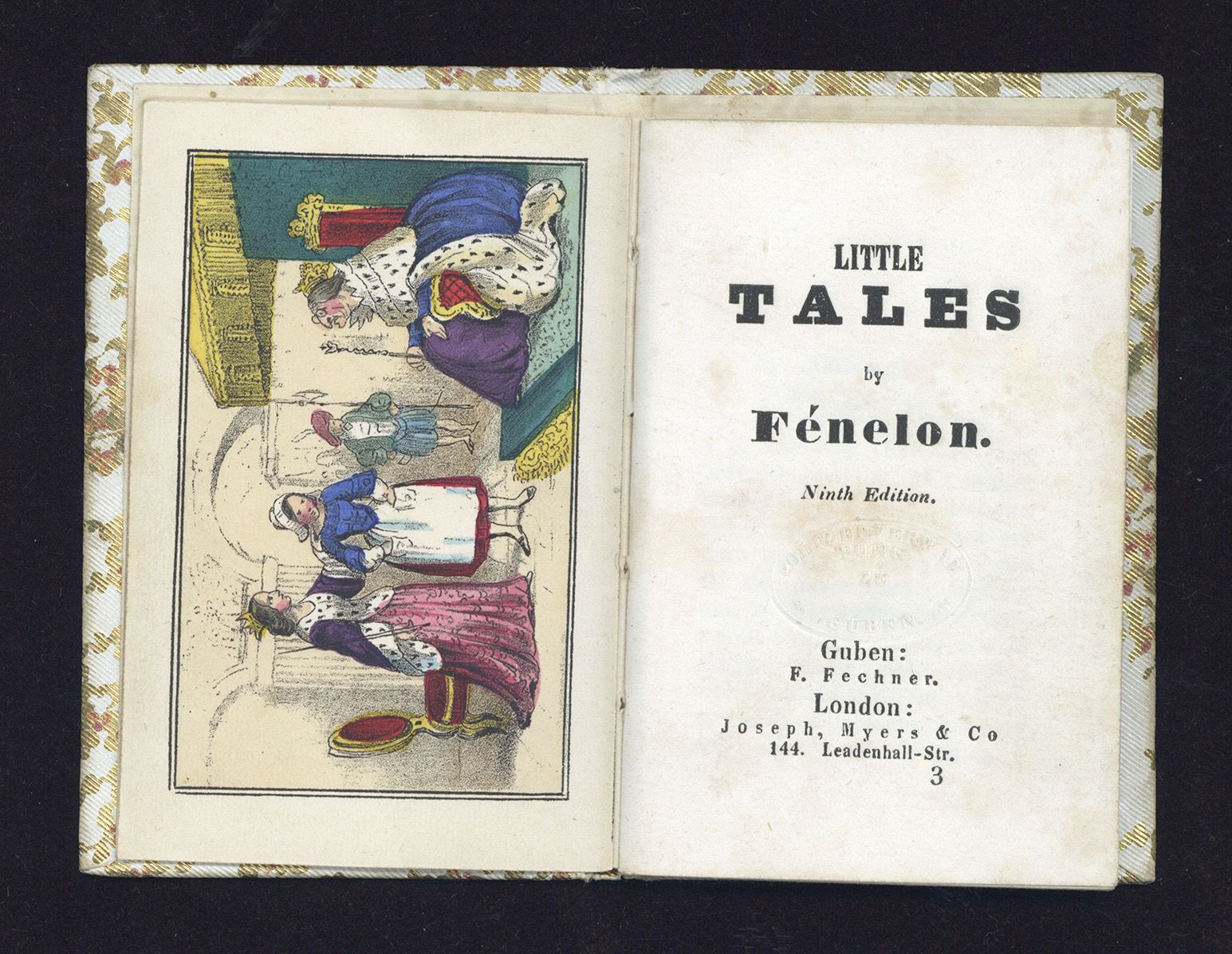

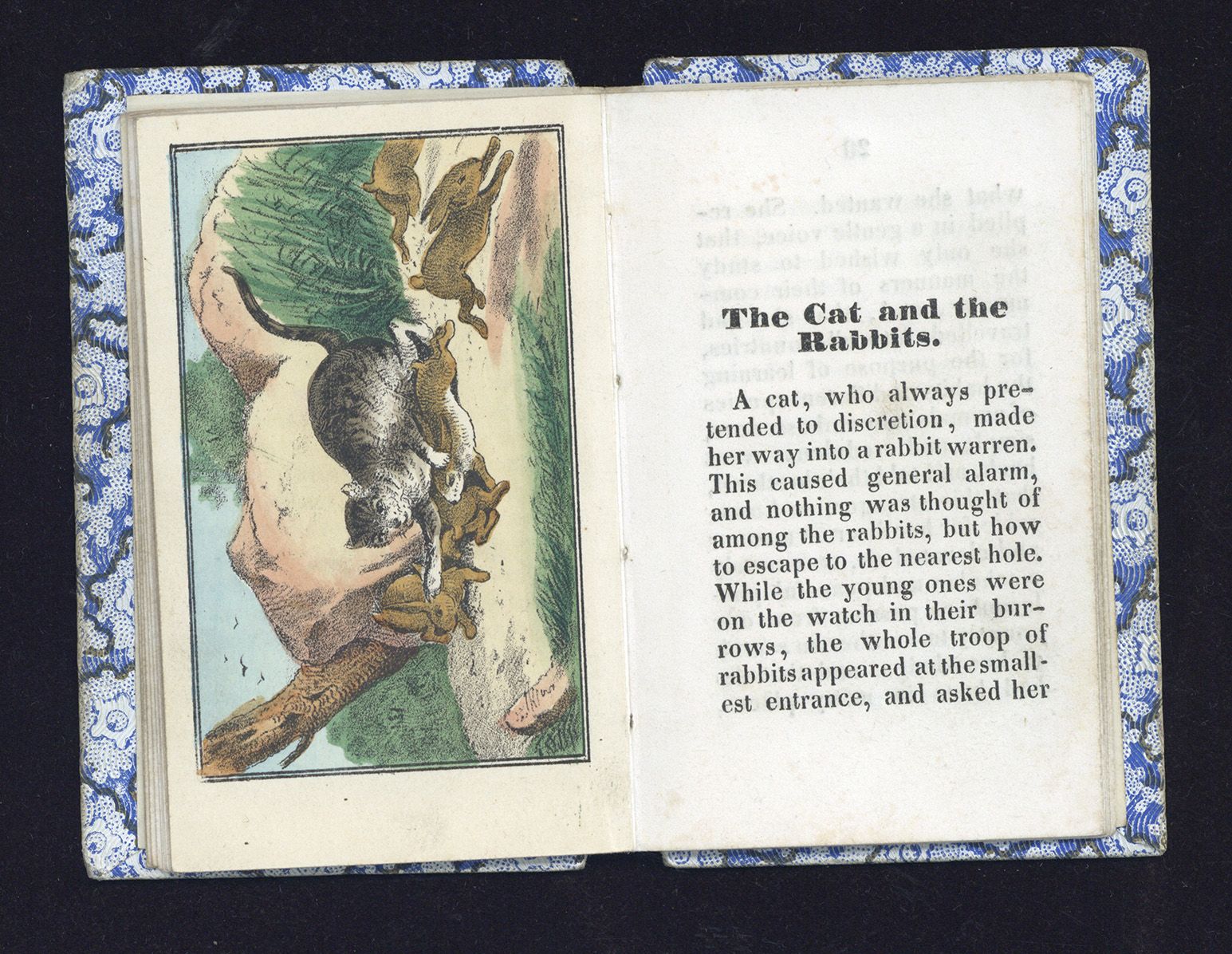

Beautiful Little Things

Miniature books were sometimes created simply because they were attractive. It was seen as a challenge to pack so much beauty into such a small creation.

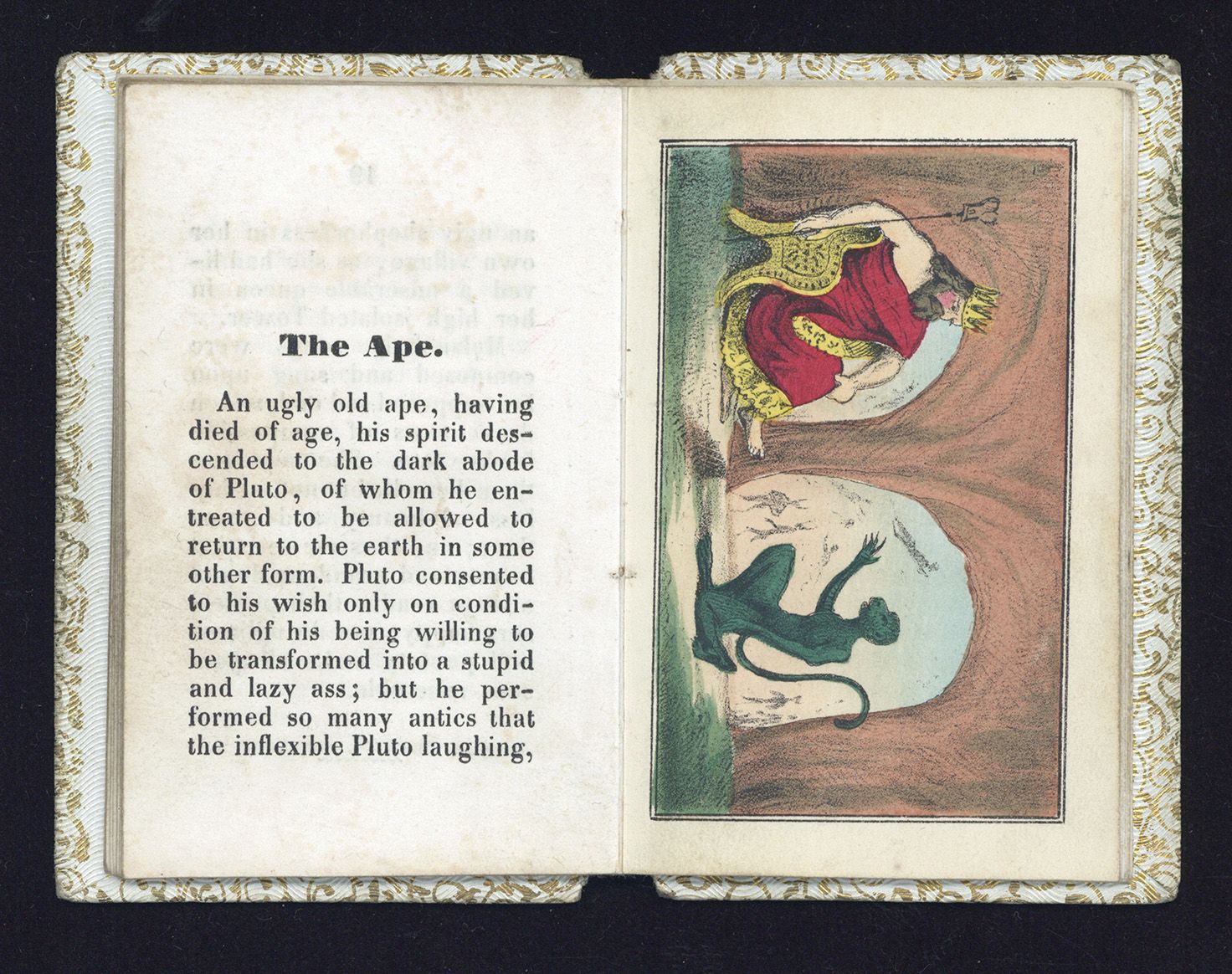

Shown here are some examples of miniature books created for children. Each volume contains appealing images that add to their beauty. It is not difficult to picture Fénelon’s tales on upper-class 19th-century bookshelves, and despite their size, being quite the centrepiece.

Fénelon, François. Little Tales. 4 vols

(Guben: F. Fechner; London: Joseph, Myers & Co., 1861)

RB 843.4 FEN, Rare Books

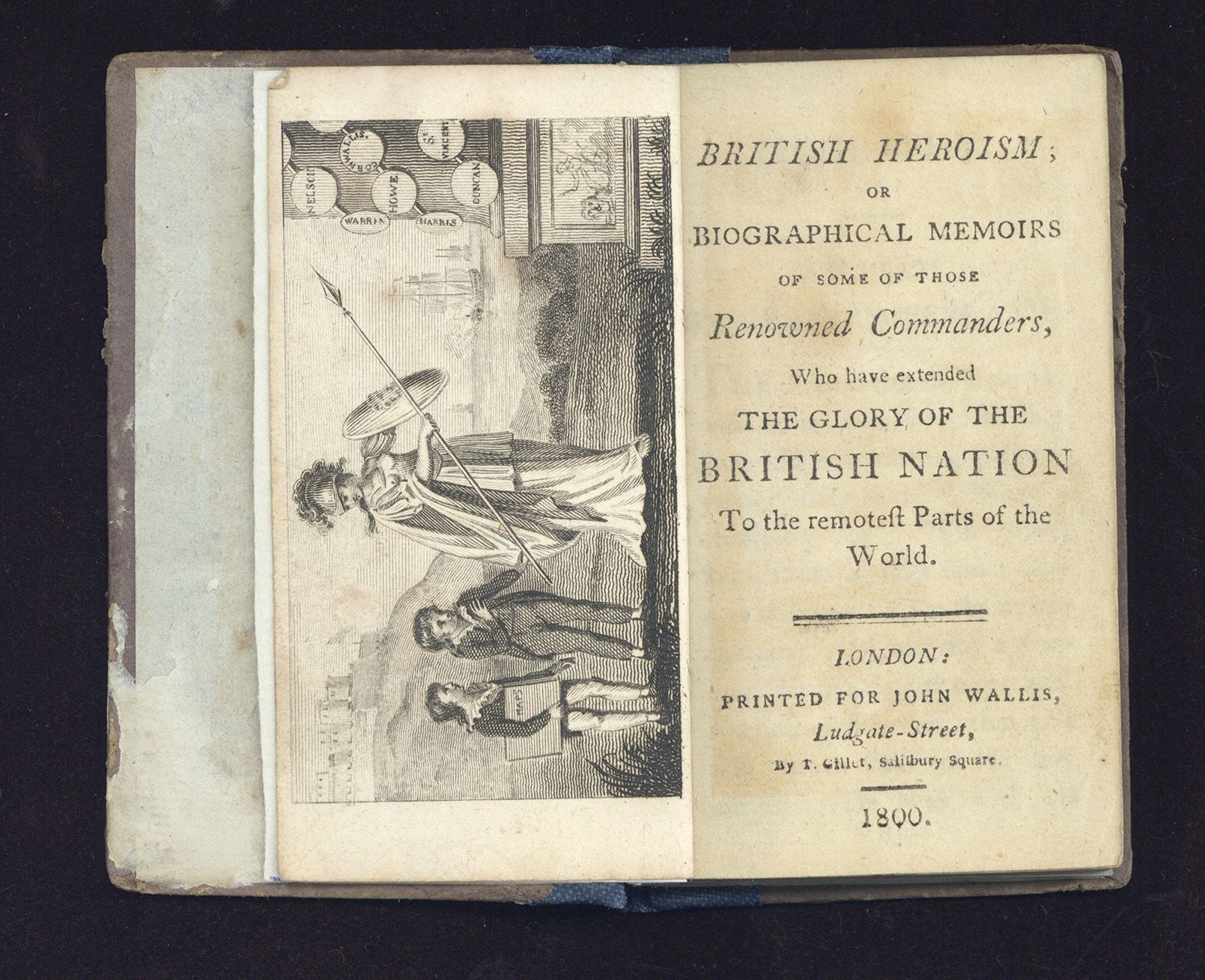

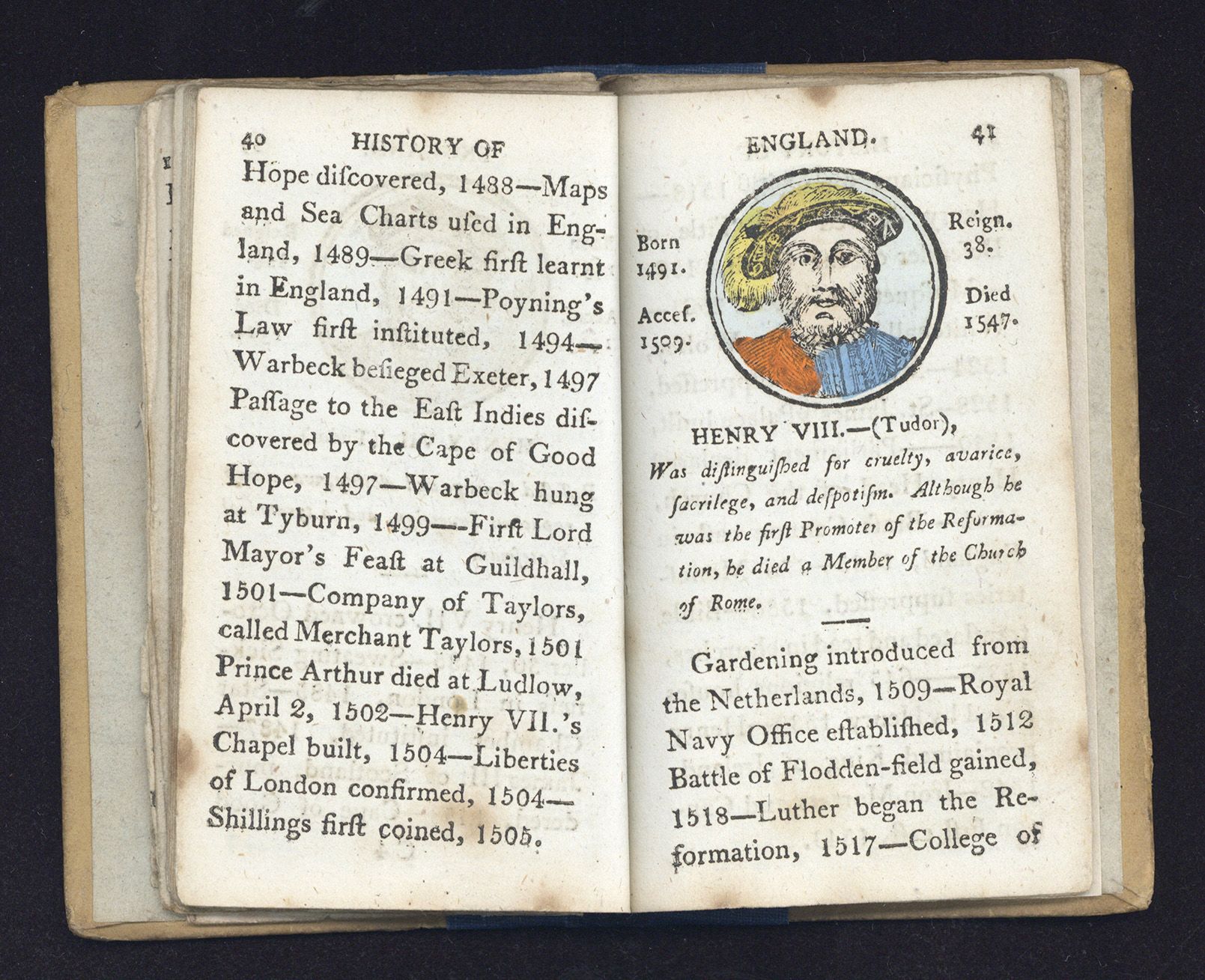

Small Books for Small Hands

Perhaps the most obvious use of miniature books is to make reading more accessible for children. Producing books small enough to fit into children’s diminutive hands increased their access to important morals within stories but also to histories of the world and other educational stories.

British heroism, or, Biographical memoirs of some of those renowned commanders who have extended the glory of the British nation to the remotest parts of the world

(London: Printed for John Wallis, 1800) Wallis 40.5 BRI, Wallis (Peter) Collection

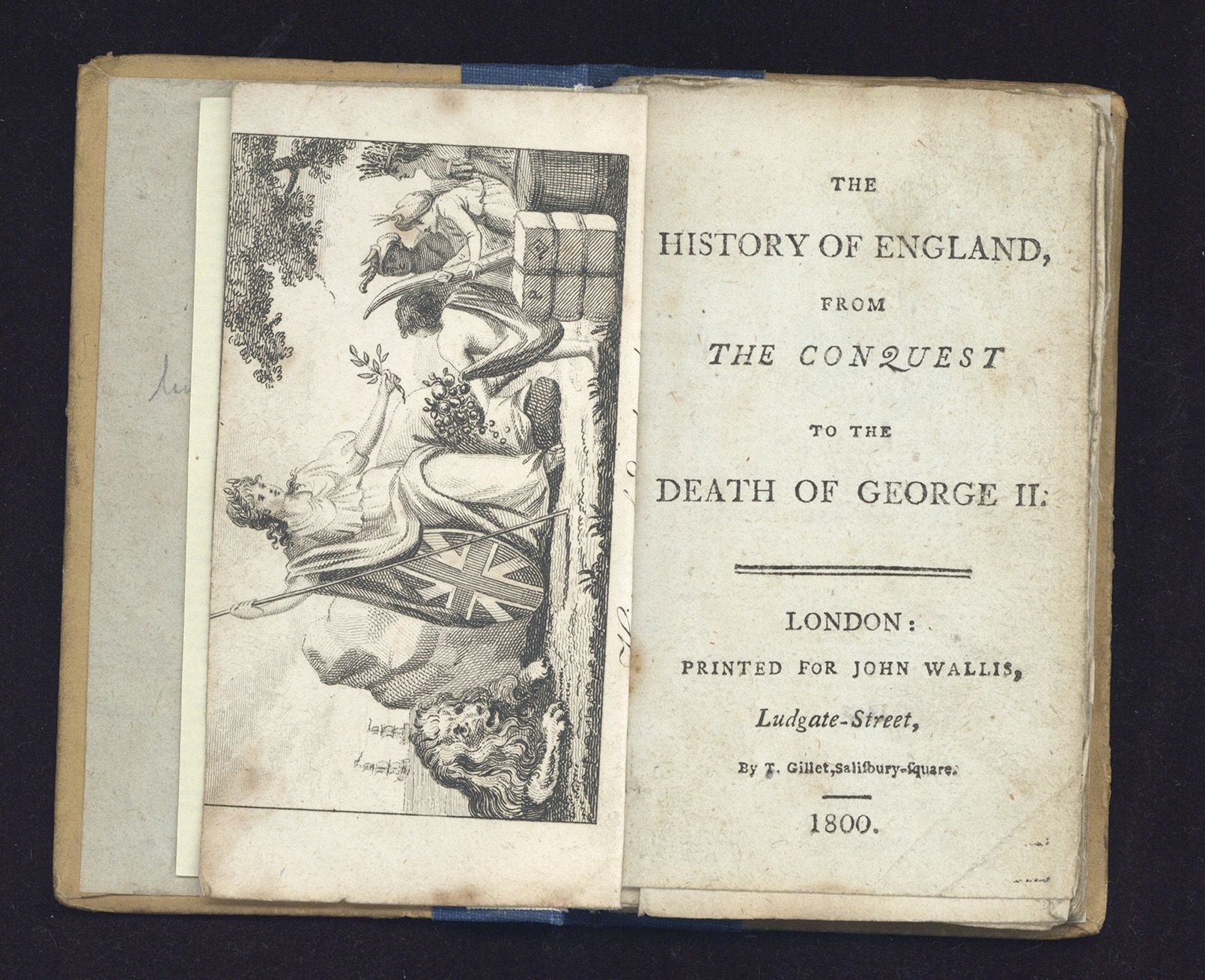

The History of England: from the conquest to the death of George II

(London: Printed for John Wallis . . . by T. Gillet, 1800)

Wallis 566.5 HIS, Wallis (Peter) Collection

Writing for Toys, Pets and Imaginary Friends

Miniatures were also useful for children and young adults to exercise their imagination, whether that be by creating miniatures themselves or consuming them. Miniature books were created for display in doll’s houses – Queen Mary’s doll’s house, designed by Edwin Lutyens, featured a library which contained miniature books written by Arthur Conan Doyle and A. A. Milne. The Brontë sisters created postage stamp-sized books for their toy soldiers to read. This tradition continues: over Covid lockdown, the British Library asked children to write small books to form the basis of an online National Library of Miniature Books for the Toy World exhibition.

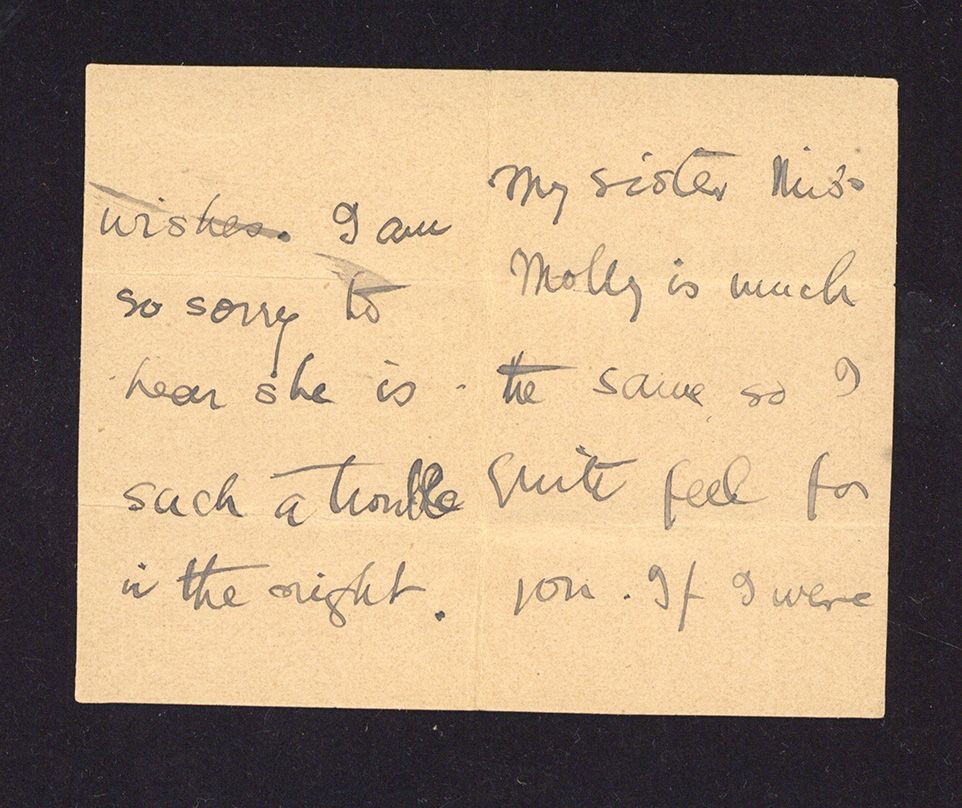

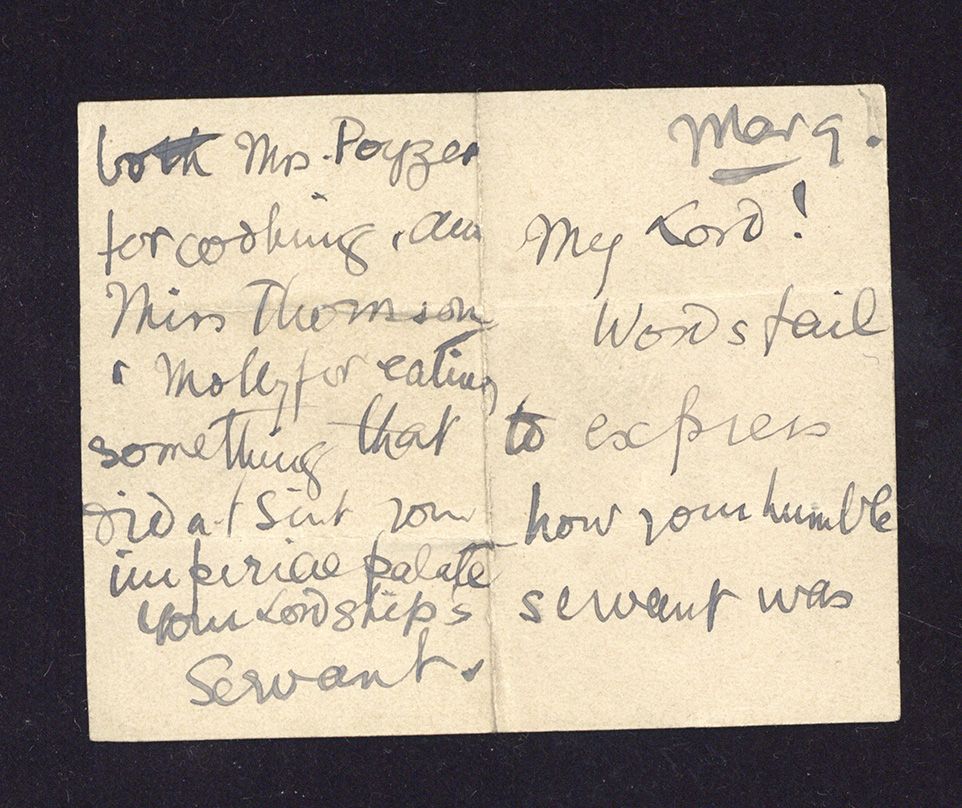

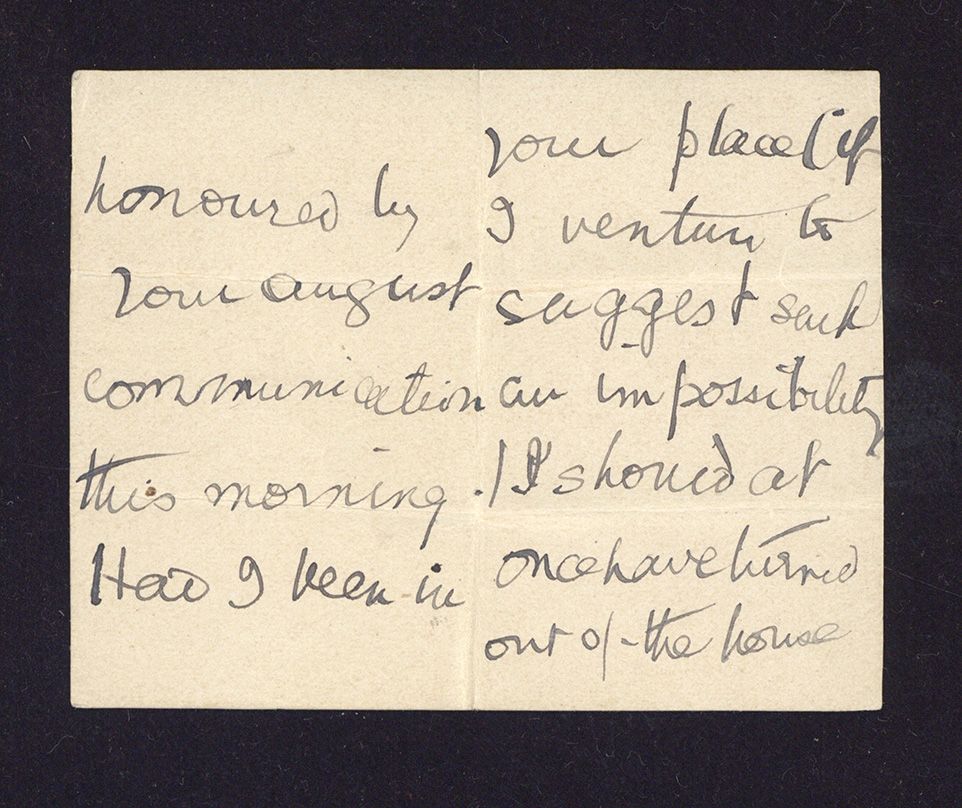

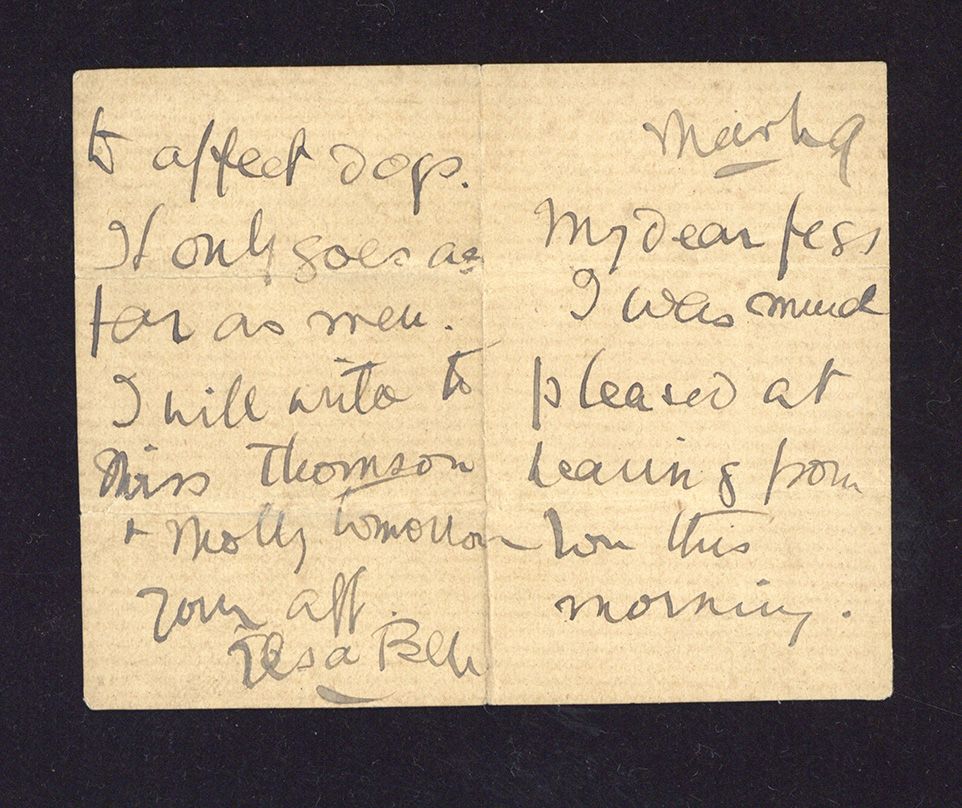

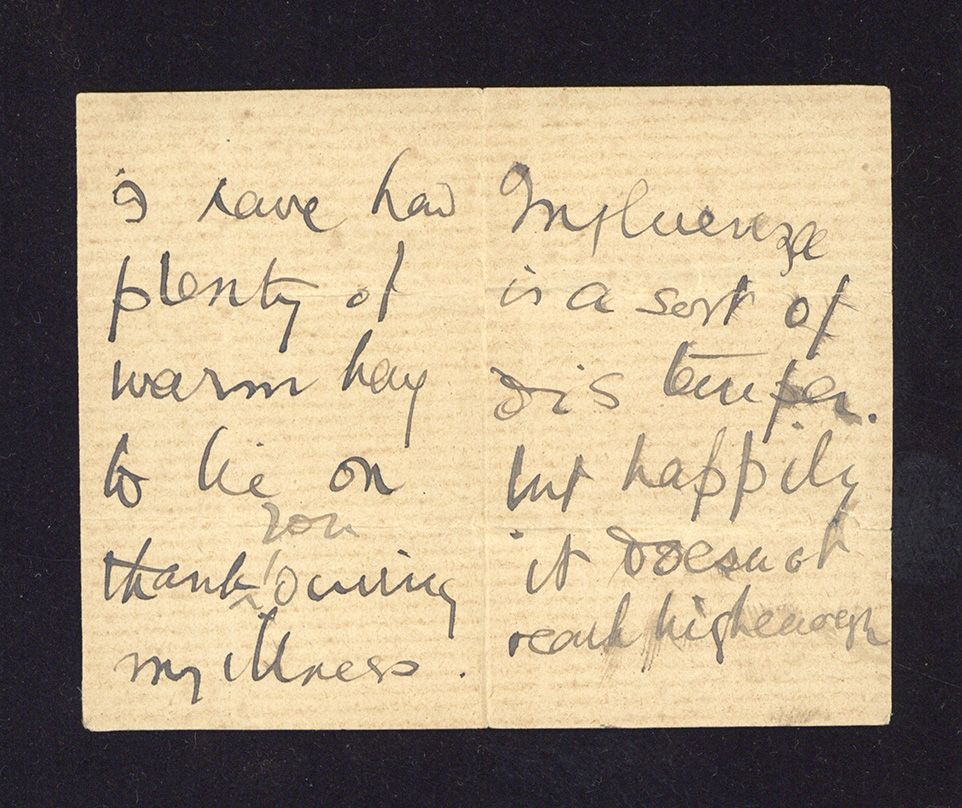

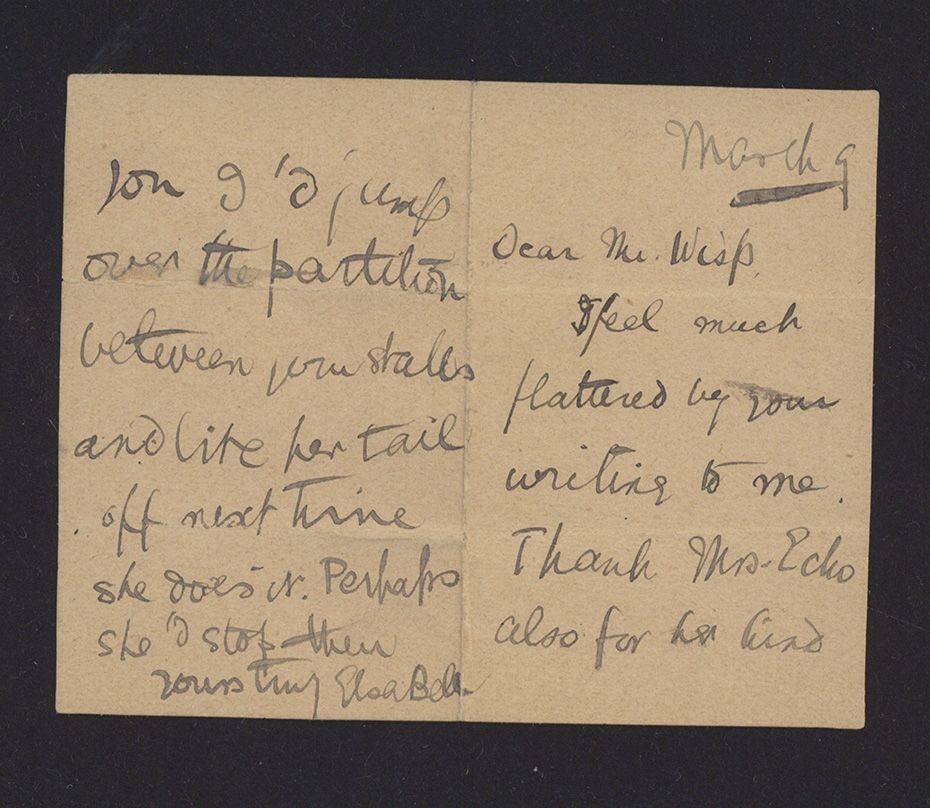

Selected pages from Bell, Elsa. Letters written to and from fictional characters (1889-1901)

CPT/2/6/1, Trevelyan (Charles Philips) Archive

A Creator’s Collection

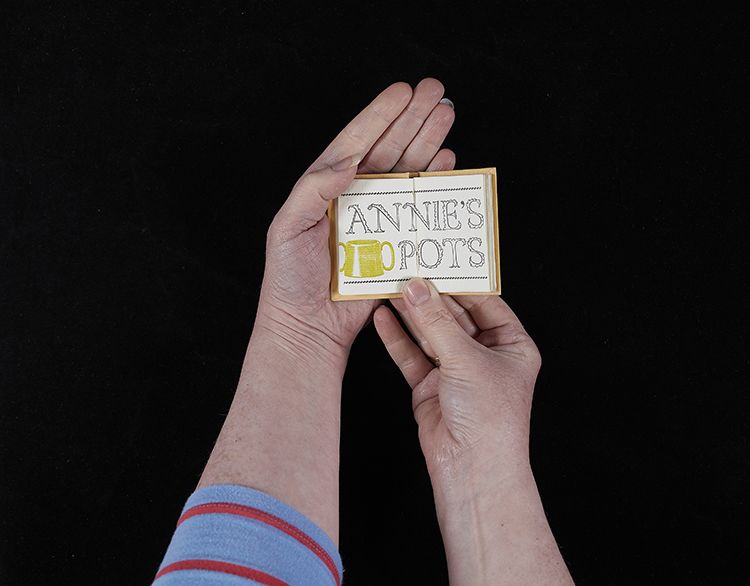

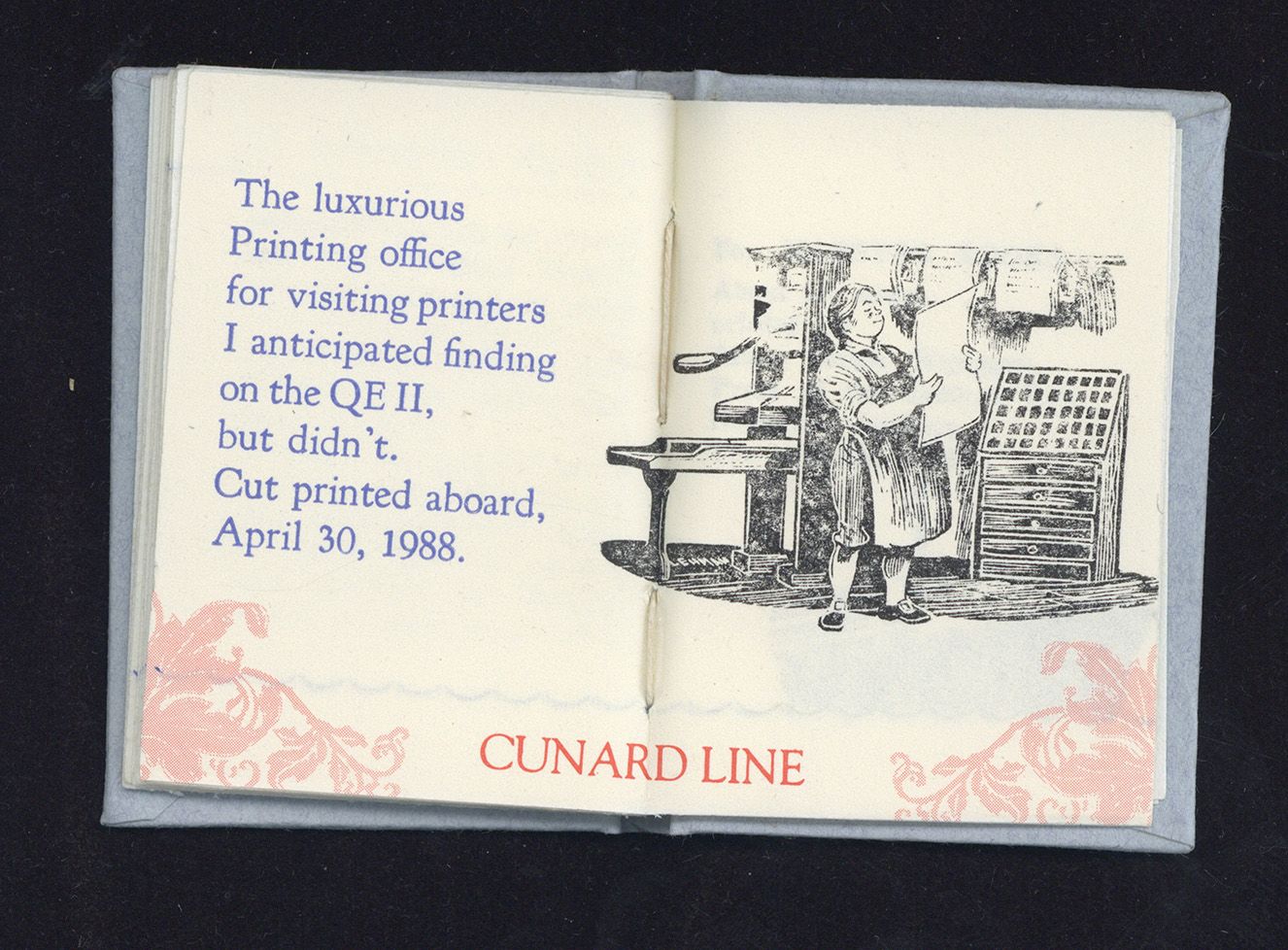

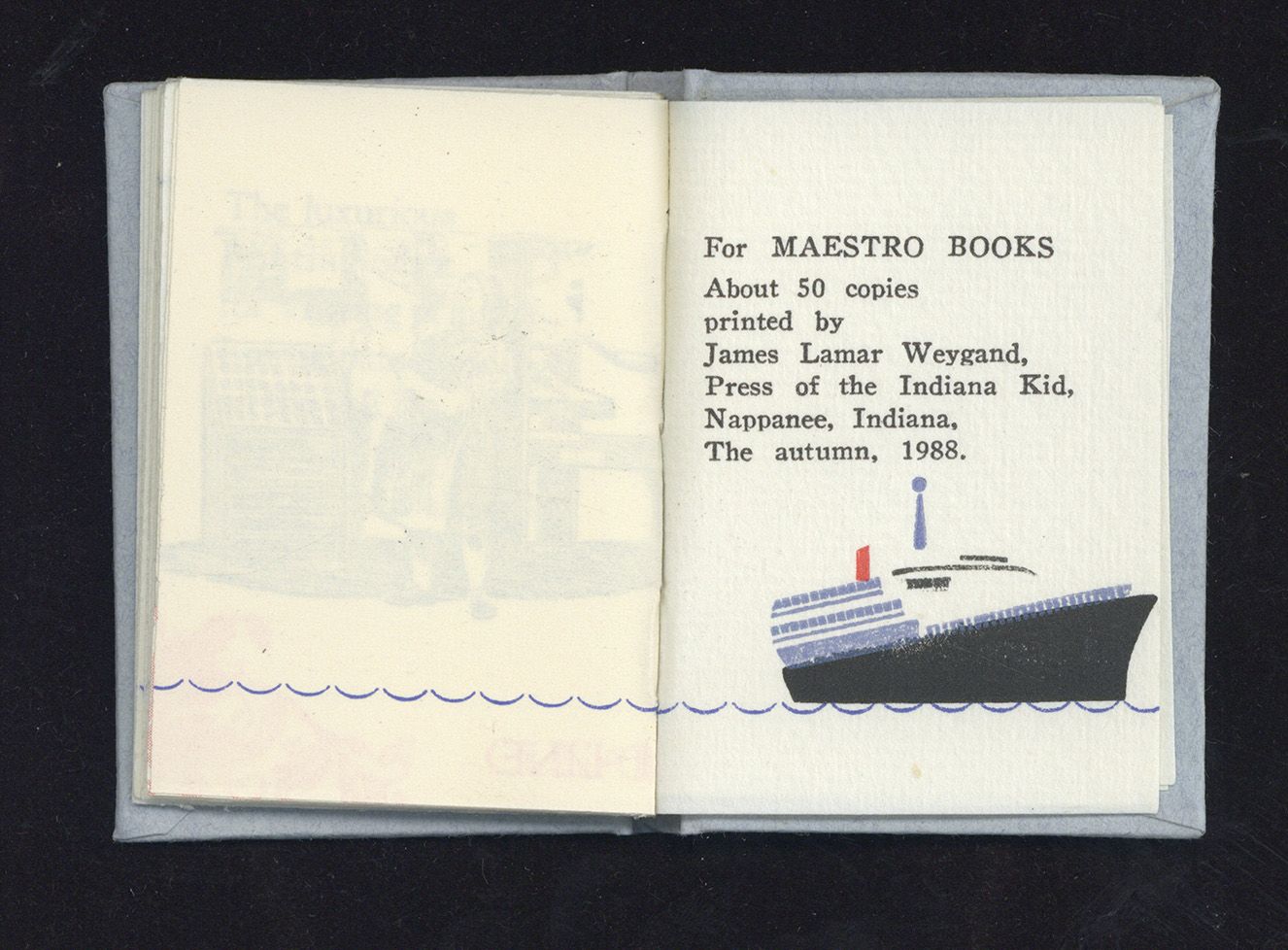

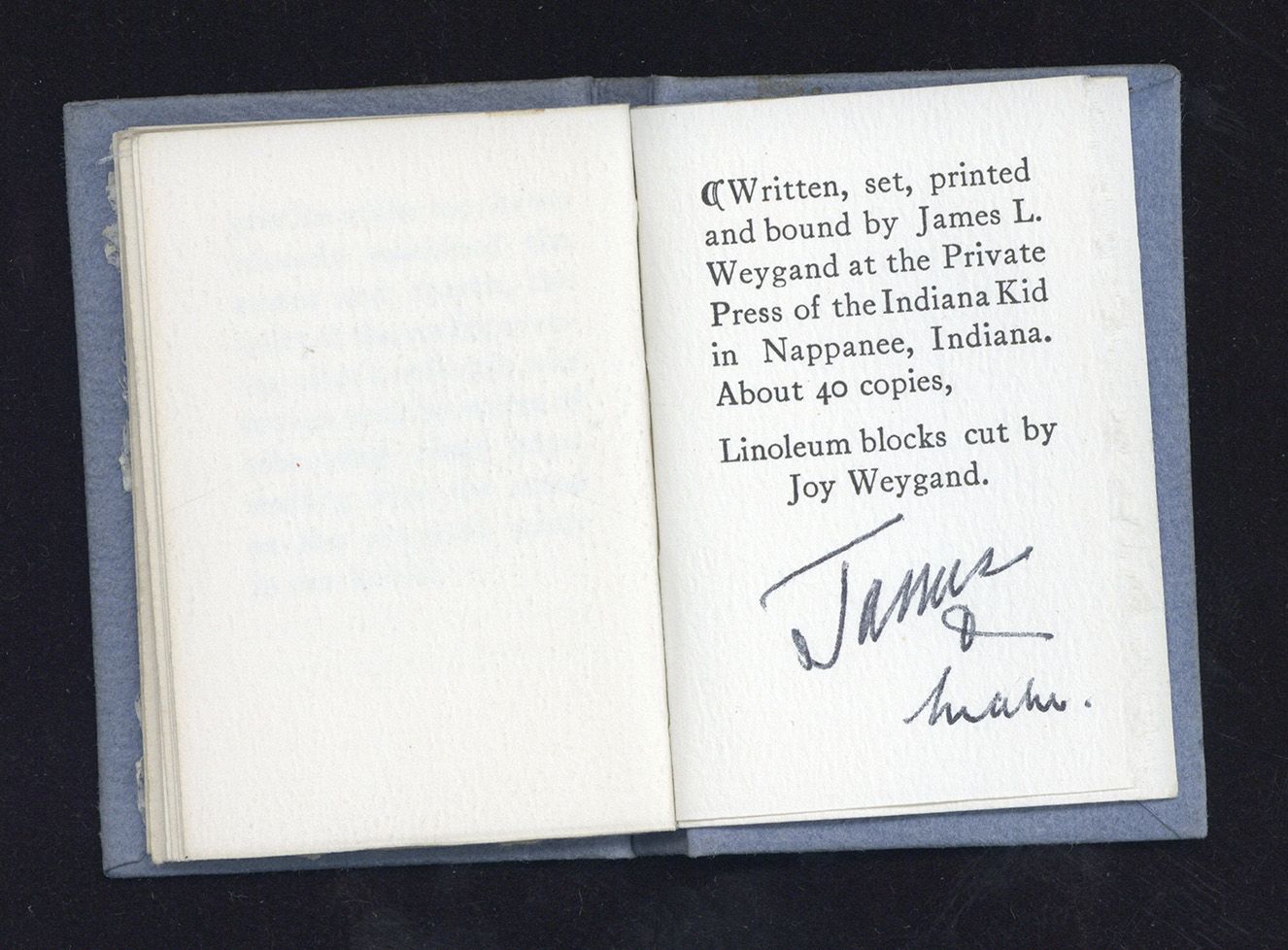

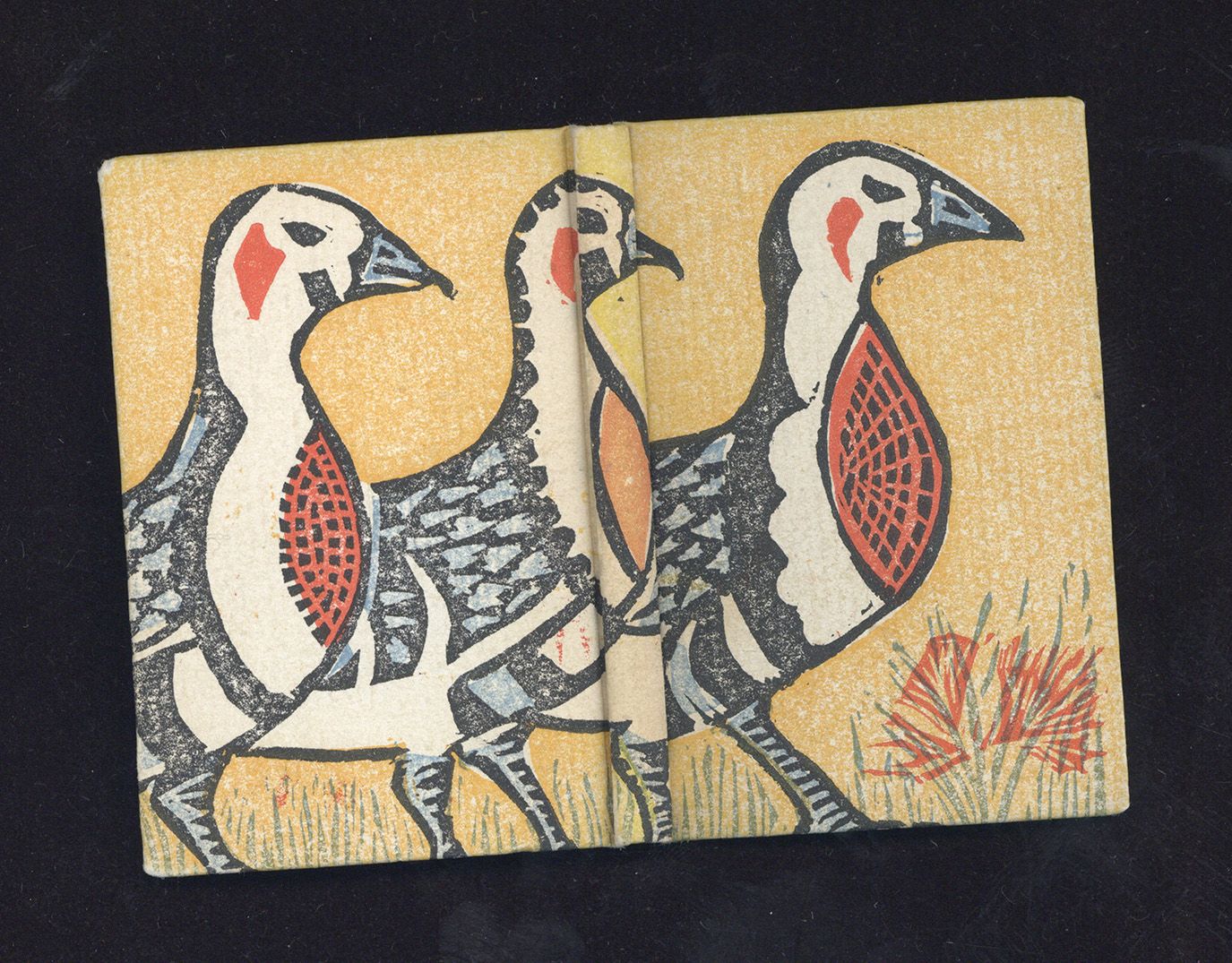

The creation of miniature books requires a lot of skill in all aspects of book production and has been aided, over time, by technological innovations. Apprentices in the book trade were tasked with creating miniature books as exercises to teach them their trades. Now, creating miniature books is a fine art and it should come as no surprise that many twentieth-century miniature books were issued from private presses. Private press publications often exhibit fine craftsmanship and a revival of traditional book-making skills. James Lamar Weygand (1919–2003), in his own words, had “a mysterious itch to print” and established The Press of the Indiana Kid in Nappanee, Indiana. Weygand both collected and created miniature books which can be seen in this cabinet.

The books have been kindly loaned to Newcastle University Library’s Special Collections and Archives for use in this exhibition by his stepson, Charles Bell, and will ultimately be bequeathed to the library.

Weygand, James Lamar. Action on the North Atlantic

(Nappanee, Indiana: Maestro Books, 1988)

About 50 copies printed by James Lamar Weygand, Press of the Indiana Kid.

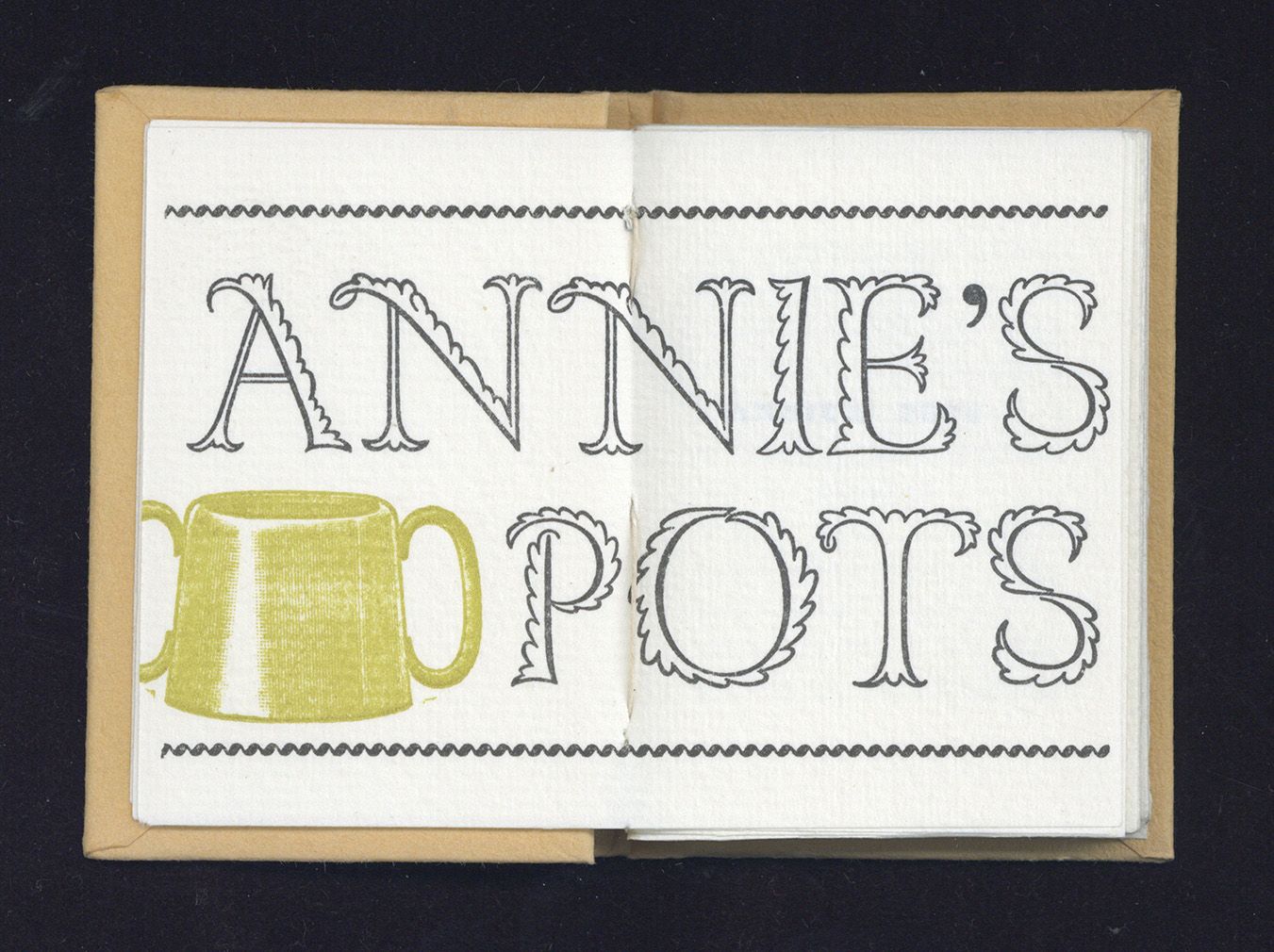

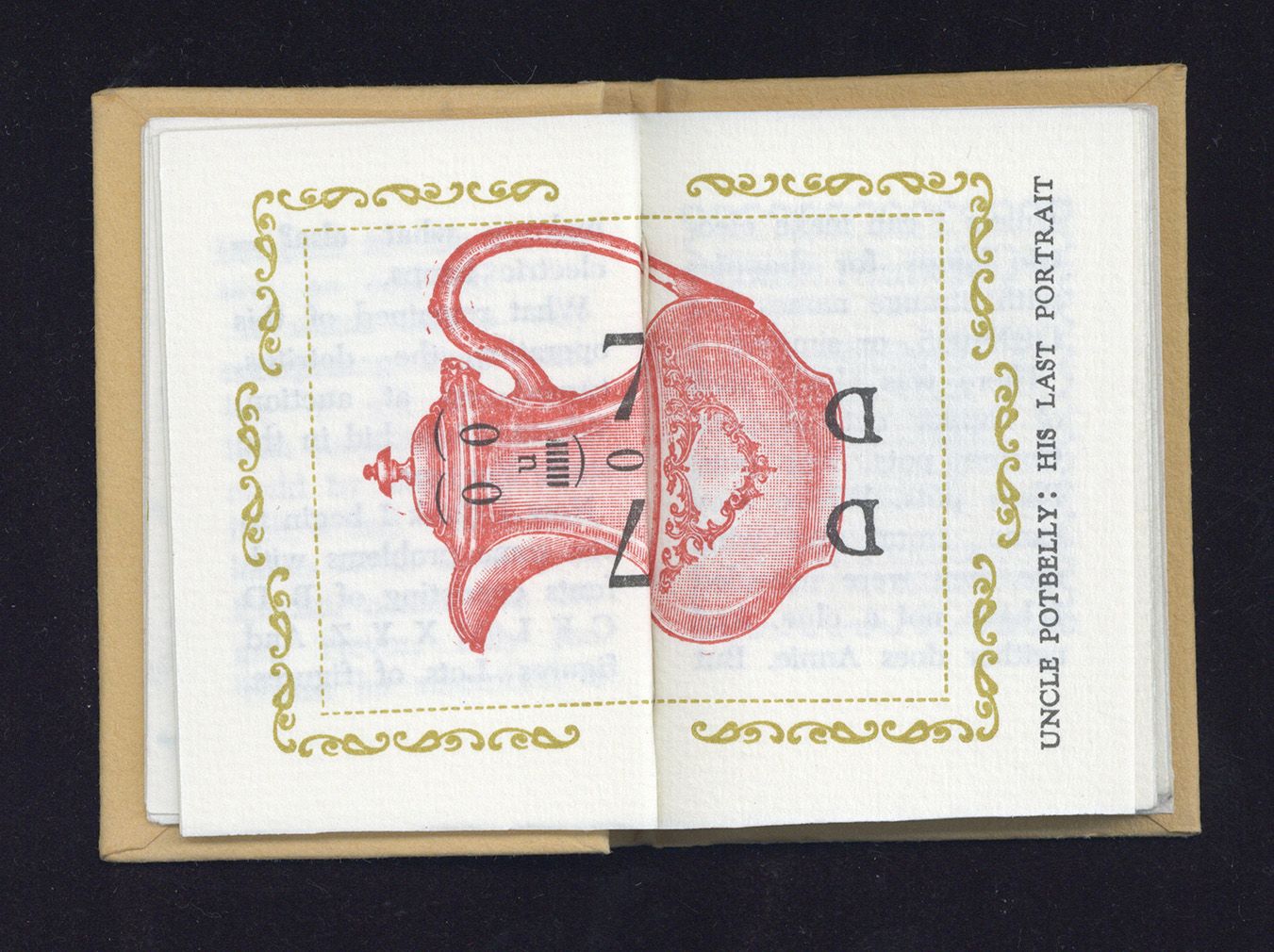

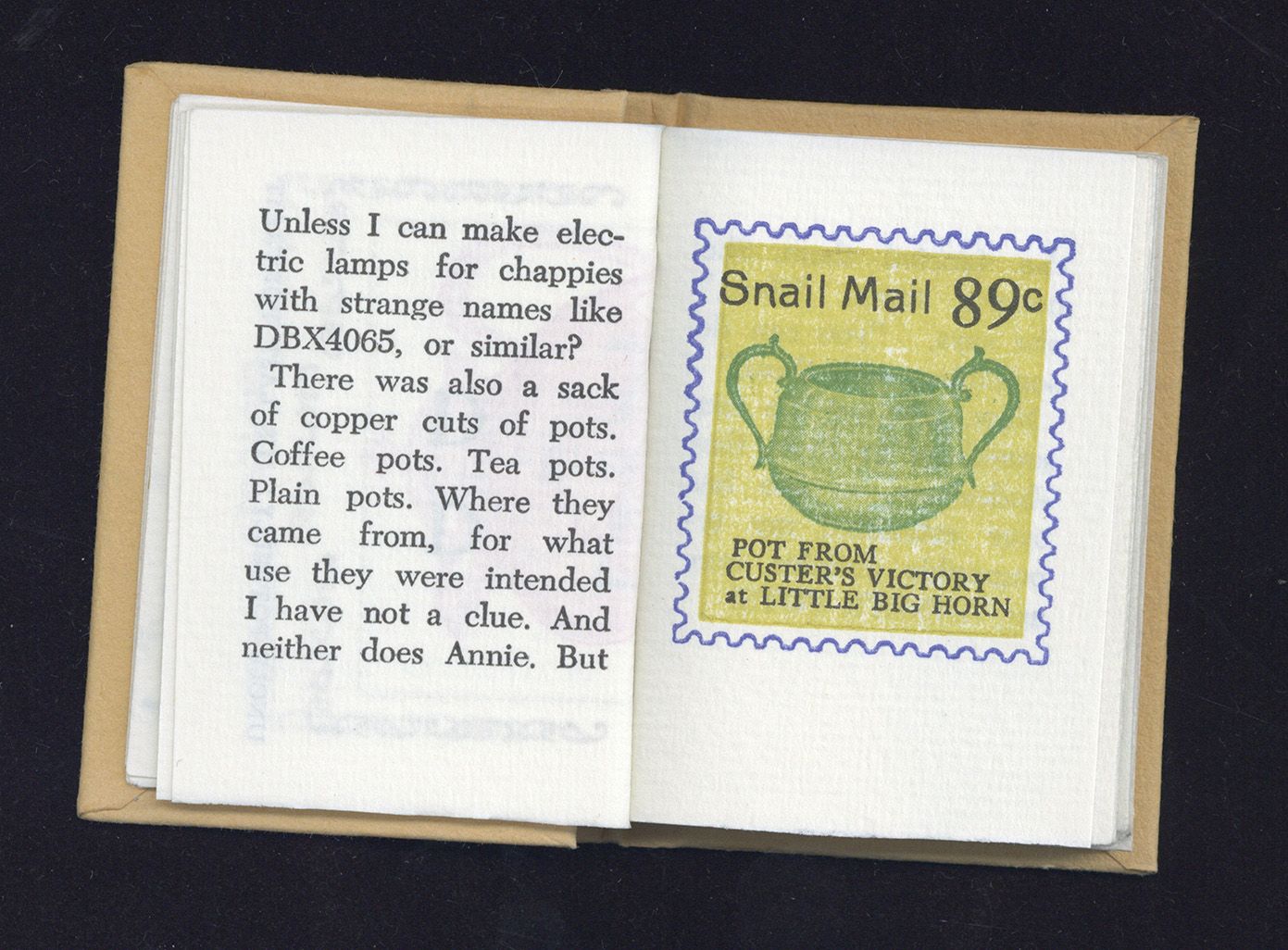

Weygand, James Lamar. Annie’s Pots

(Nappanee, Indiana: Maestro Books, [19--?])

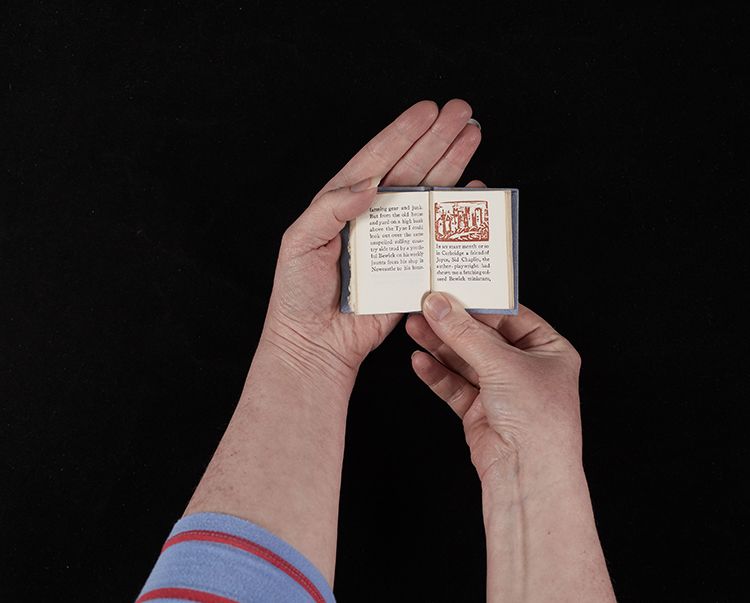

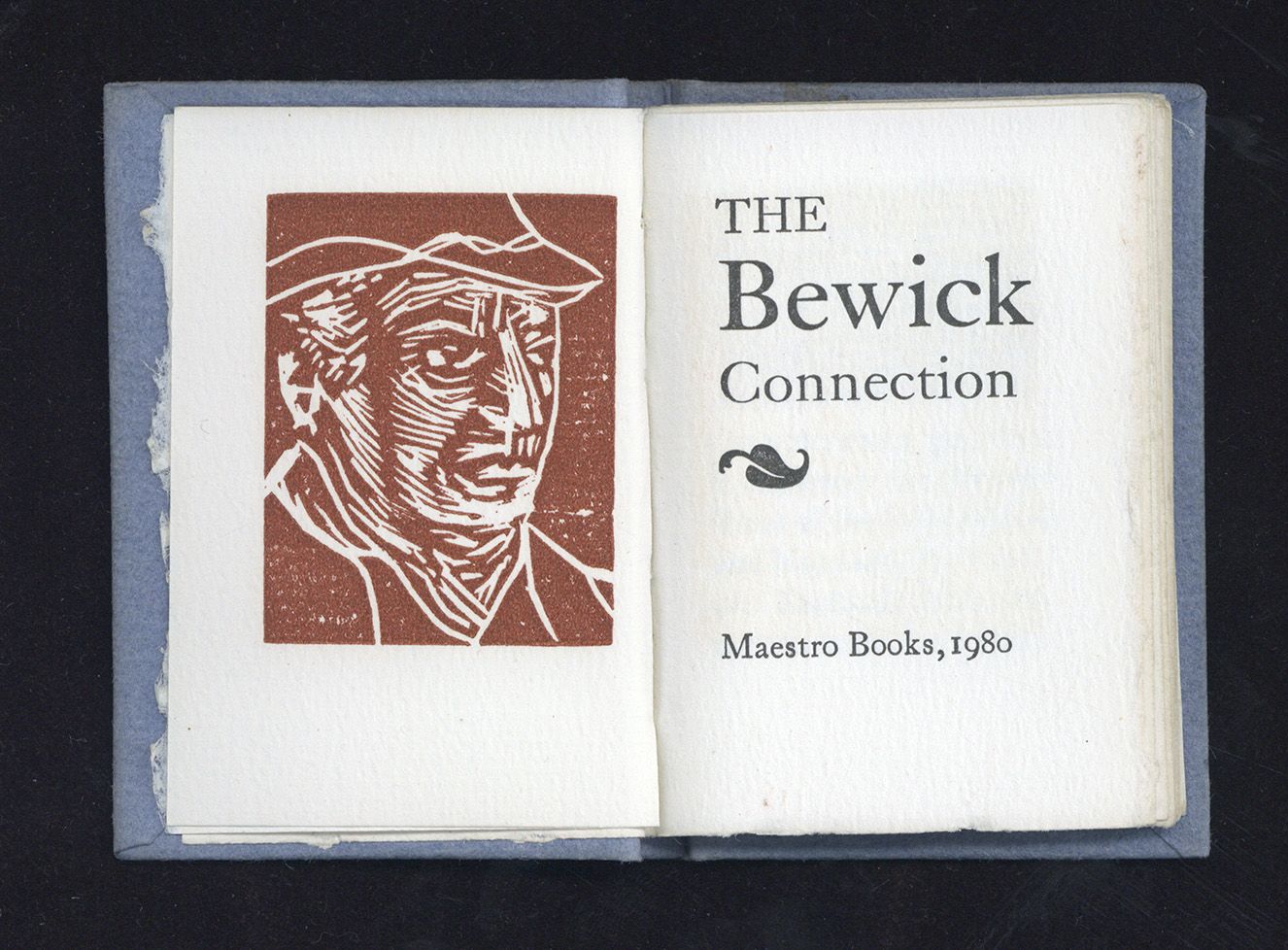

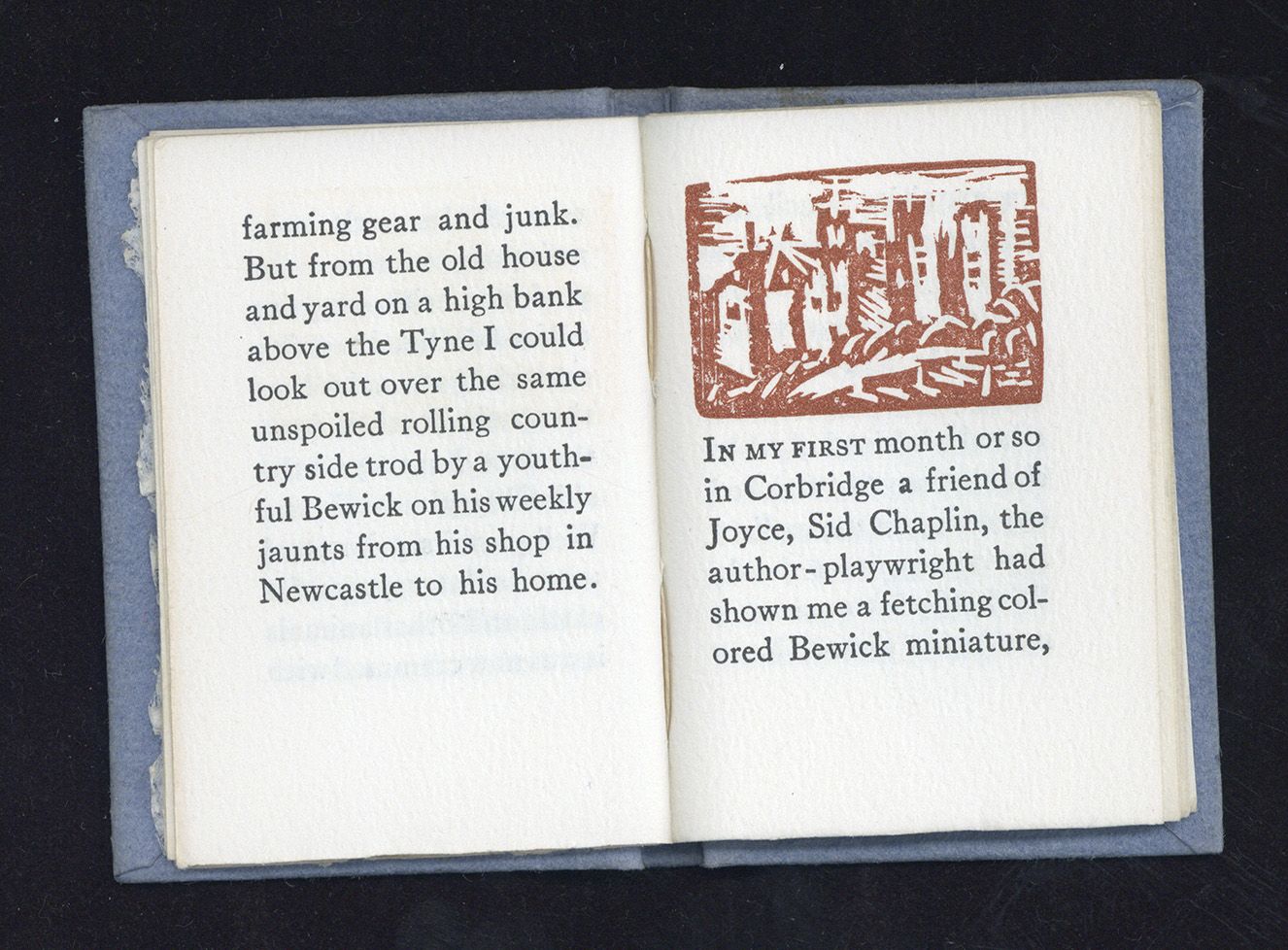

The Bewick Connection has its own very interesting connections to North East England and to Newcastle University in particular. The creator of these books, James Lamar Weygand, married Joy and they honeymooned in Northumberland. This book tells some of their honeymoon story, including a visit to the home of the 18th-century naturalist and engraver Thomas Bewick. (Newcastle University Special Collections has books by Thomas Bewick and the archive of Sid Chaplin who is also referenced in this Weygand miniature.)

Weygand, James Lamar. The Bewick Connection

(Nappanee, Indiana: Maestro Books, 1980)

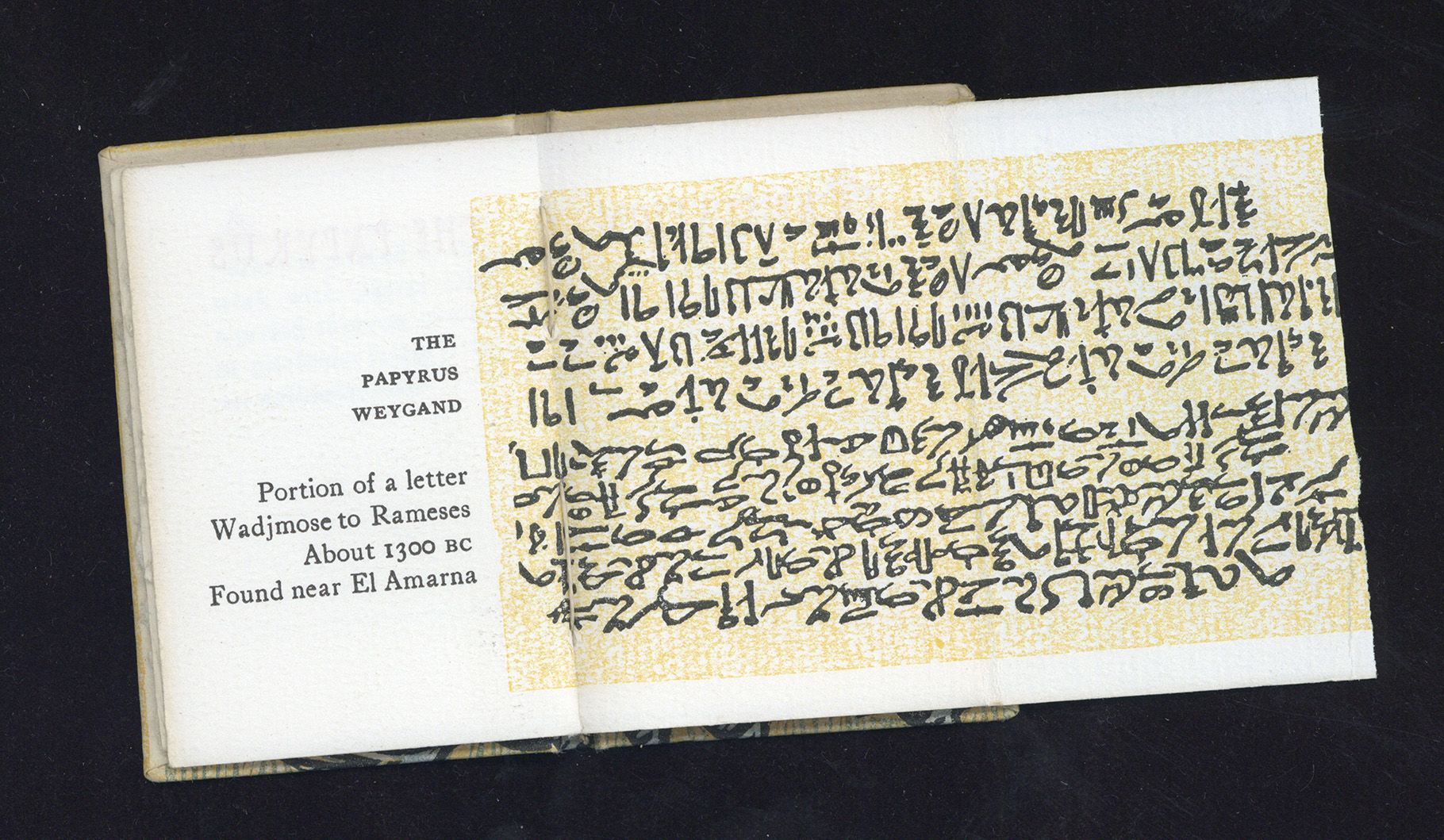

Weygand, James Lamar. The Papyrus Weygand

(Nappanee, Indiana: Maestro Books, 1980)

Find Out More

Curated by Robinson Bequest Student Kiah Edwards. The miniature books by James Lamar Weygand were kindly loaned to the exhibition by Charles Bell.

Newcastle University Library Special Collections & Archives collects, preserves, promotes and provides access to unique and distinctive books and archives. These resources are made available not only to our own University staff and students, but to researchers from other institutions and to the wider community.

To find out more about our holdings please look at our Collections Guide. To discover how you can consult materials see Using our Collections.