Broadsides: Revealing Newcastle's Past Through Popular Print Culture

A Virtual Exhibition by Newcastle University Special Collections & Archives

Introduction

The Broadsides

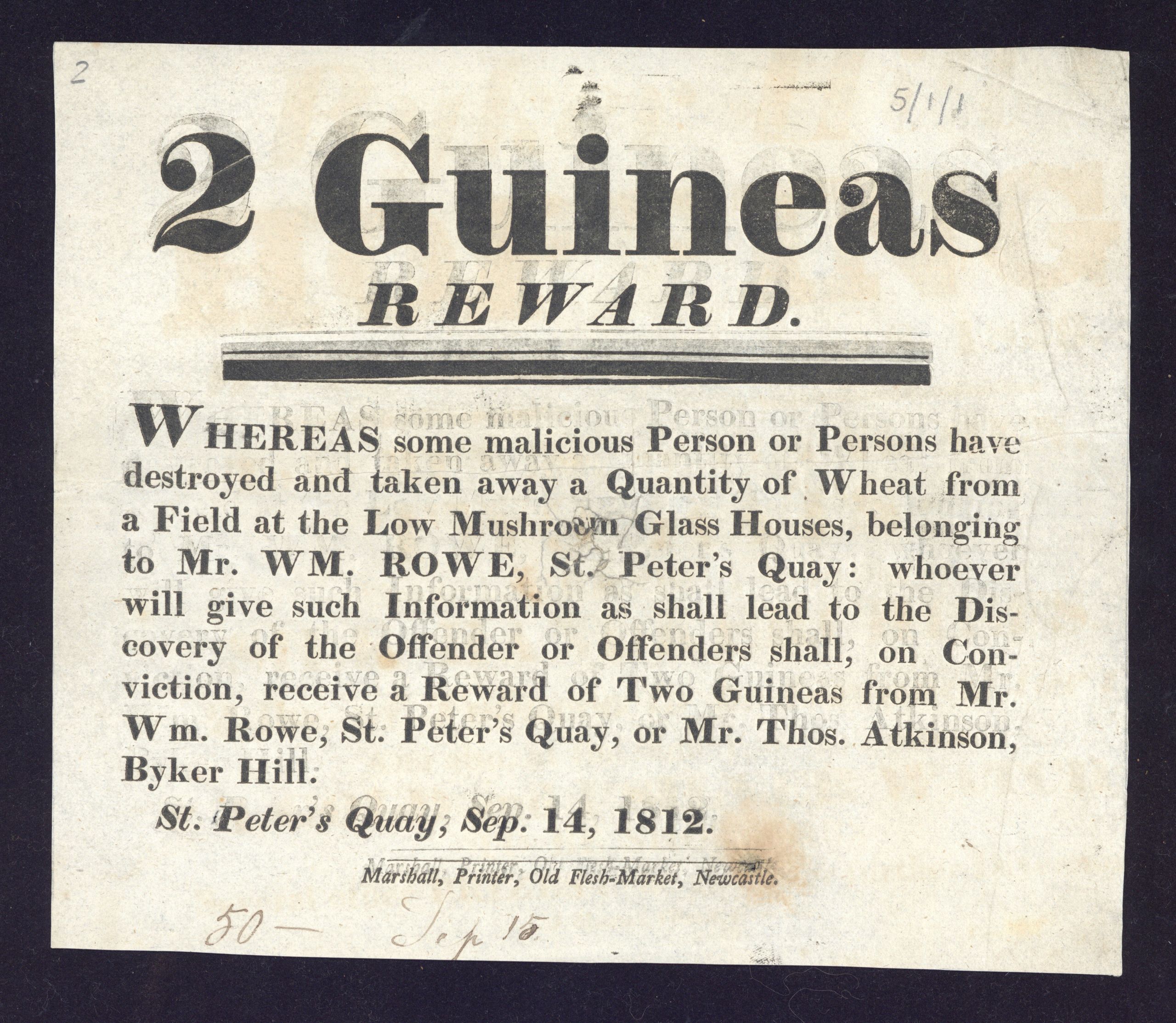

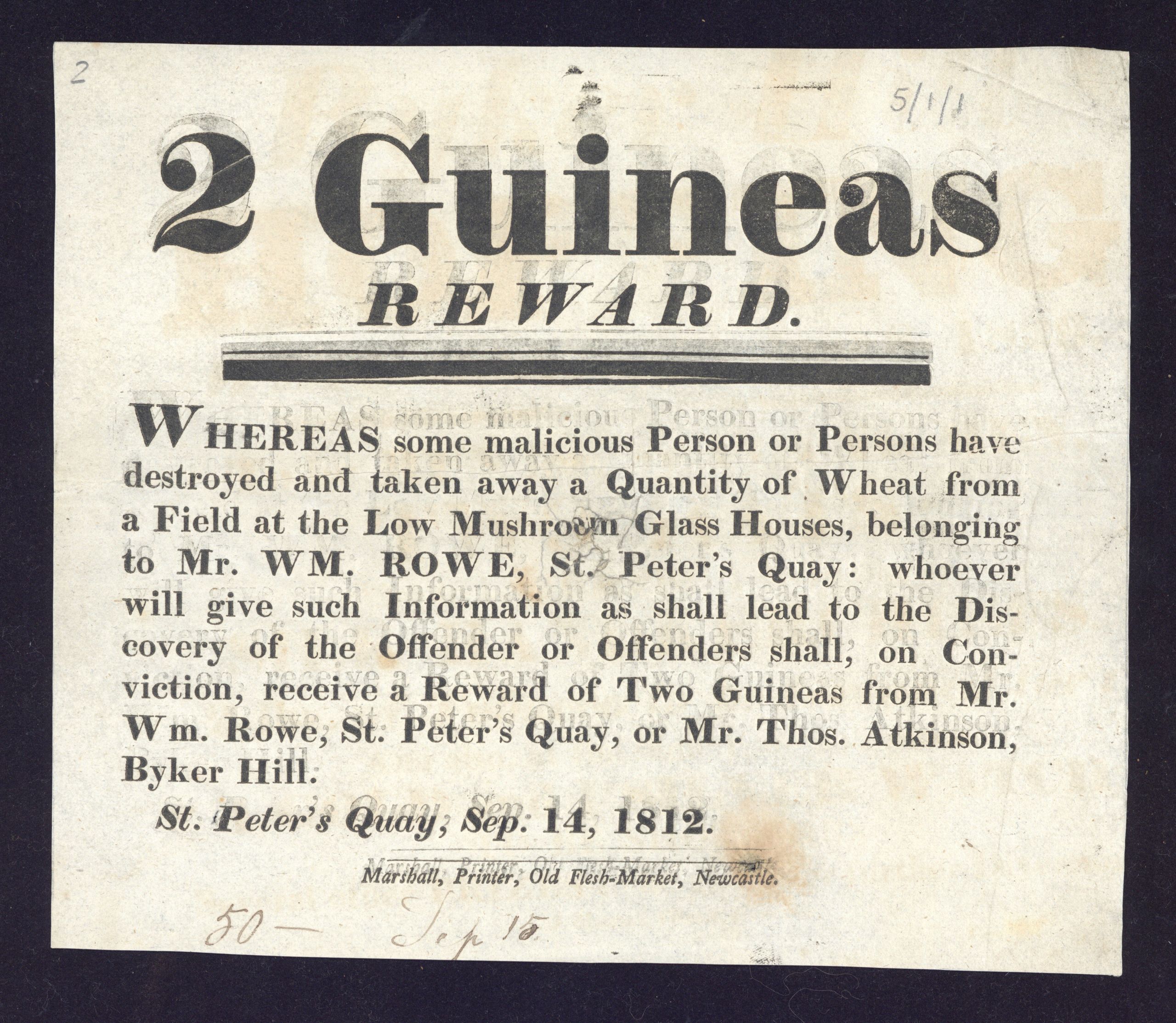

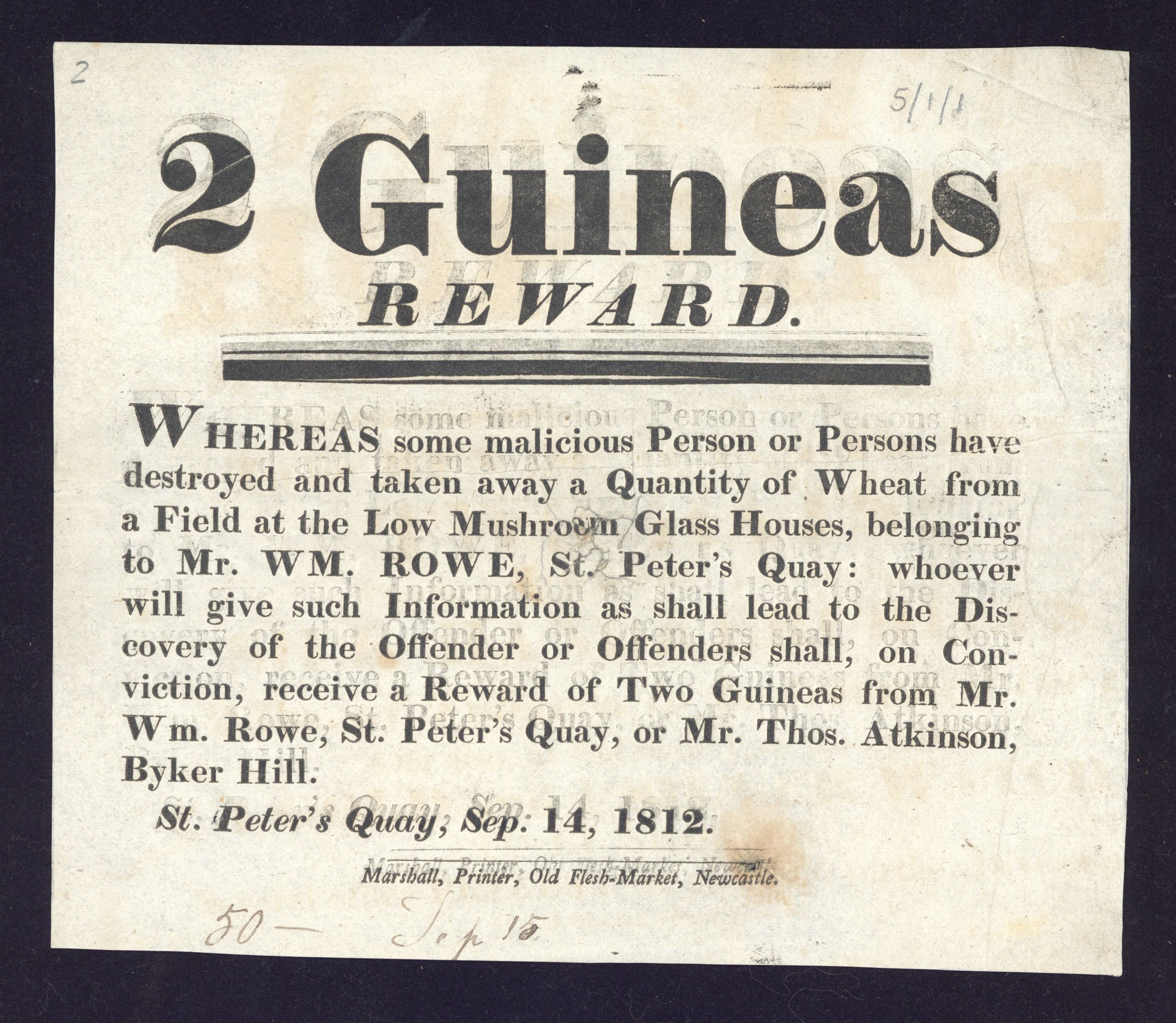

Reward poster 1812, Broadsides 5/1/1, Broadsides, Newcastle University Special Collections, GB186

This reward poster concerns the theft of wheat from a field owned by William Rowe of St. Peter’s Basin, information about which is sought for a reward of two guineas (worth roughly £93.00 today). There was no modern police force before 1836 and even then, policing was inconsistent across the country. Prosecutions were often brought by private individuals; prosecution associations were community organisations whose members paid dues to cover the costs of private prosecutions. We can see from the annotation at the bottom of the leaf that 50 copies of this reward poster were printed.

William Rowe was a shipbuilder (active 1756-1810). His shipyard had been sold in 1810 (two years before this incident) but had constructed 12 ships for the Admiralty during the Napoleonic Wars, when it was the largest shipyard on the River Tyne.

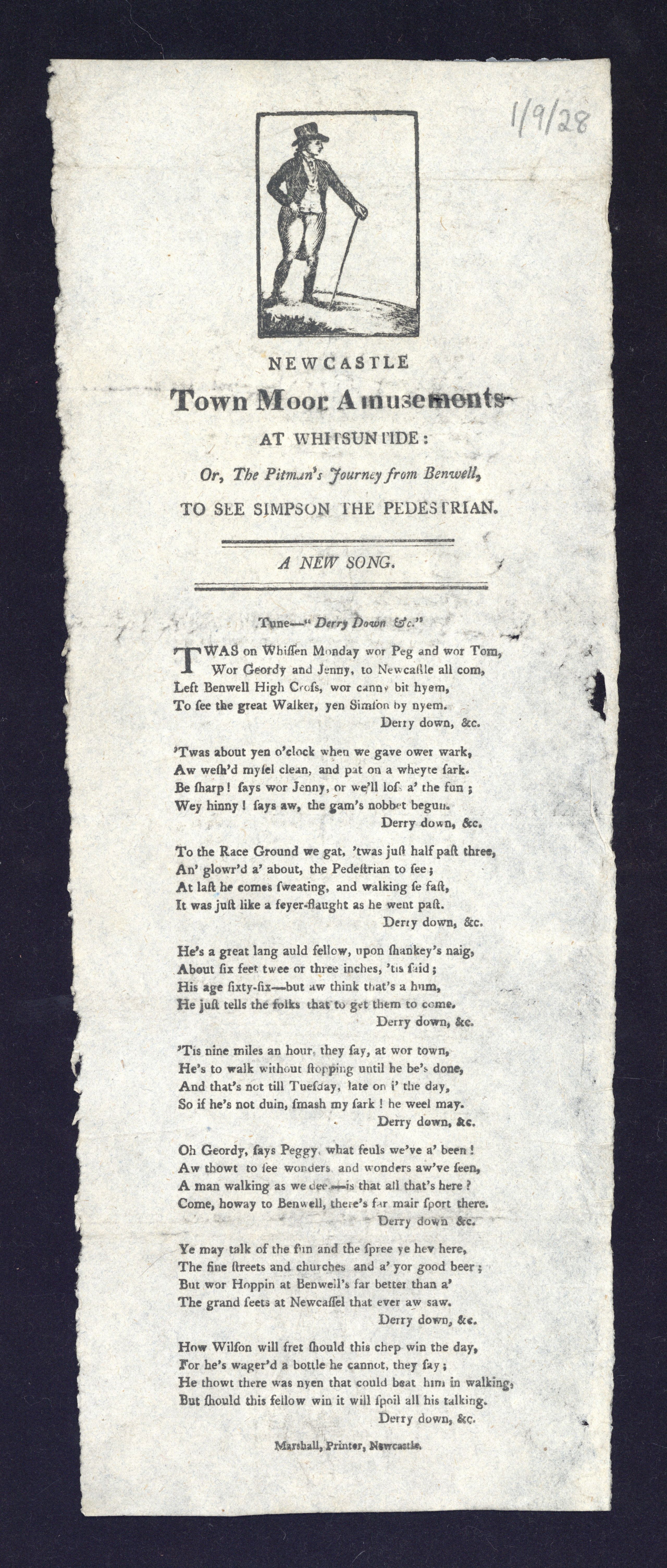

Newcastle’s Town Moor was used for foot races in the early-Nineteenth Century, indeed, Newcastle and Gateshead were great centres of ‘pedestrianism’: a popular spectator sport and regular fixture at fairs that, until 1828, required competitors to walk against the clock. For example, in 1822, George Wilson walked 90 miles in 24 hours, around a half-mile circuit. In 1828, Peter MacMillan walked 110 miles in 24 hours.

Newcastle Town Moor Amusements at Whitsuntide: Or, The Pitman's Journey from Benwell, to see Simpson the Pedestrian c. 1822, Broadsides 1/9/28, Broadsides, Newcastle University Special Collections, GB186

This broadside is a song about a Cumbrian pedestrian, or competitive walker, called John Simpson. On Whit Monday, 29th and 30th July, he tried to walk 96 miles but failed at both attempts. In the song, Peggy, Tom, Geordy and Jenny go to Newcastle from Benwell “to see the great Walker”, Simpson. He is said to stand above six feet tall, be aged sixty-six and walking at a pace of nine miles per hour and not stopping until he is done. Peggy is not impressed: “A man walking as we dee – is that all that’s here? / Come, howay to Benwell, there’s far mair sport there”. Meanwhile, George Wilson is rumoured to have bet a bottle of beer that Simpson can’t beat him at walking.

The Changes on the Tyne c.1830, Broadsides 4/1/45, Broadsides, Newcastle University Archives, GB 186

This undated song was probably written in the early-mid 1830s and describes the development of Newcastle, particularly along the river but, at the same time, it comments on people’s lives. The song is written by someone that claims to be, or have been, a skipper on the Tyne. He remembers when there were green fields on both sides of the Tyne. Now, there are furnaces – mostly likely iron furnaces - all along the river as far as the coast. These furnaces belch sulphur, vapour, smoke and steam.

The song references Anthony Clapham, a Quaker soap maker, brewer and pharmacist who, in 1833, built an 80-metre-high chimney that became a landmark (“But now Anty Clapham the quaker, has filled a’ the folk wi’ surprise / For he’s lately built up a lang chimley within a few feet o’ the skies.”). William Losh was the proprietor of both the Walker Ironworks and Walker Alkali Works: “There’s Losh’s big chimley at Walker, its very awn height maks it shake”. Isaac Cookson was a glassmaker that established an alkali works near Jarrow slake, shortly after 1823: “And if Cookson’s again tumble ower, it will make a new quay for the slake”. These chimneys dominated the skyline and were terrible polluters. Cookson’s alkali works were closed in 1843, after a series of prosecutions brought about by the damage caused by smoke and effluent gases.

The replacement of light barges with steamers and of gigs with omnibuses has made travelling more expensive but the shorter journey times have given people more leisure time at their destinations. Discarded sand ballast has been transformed into picturesque hills while builder Richard Grainger has magically revitalised the town centre: his new meat market was built in 1835 and later became known as Grainger Market, and the rest of his scheme included new homes and private houses.

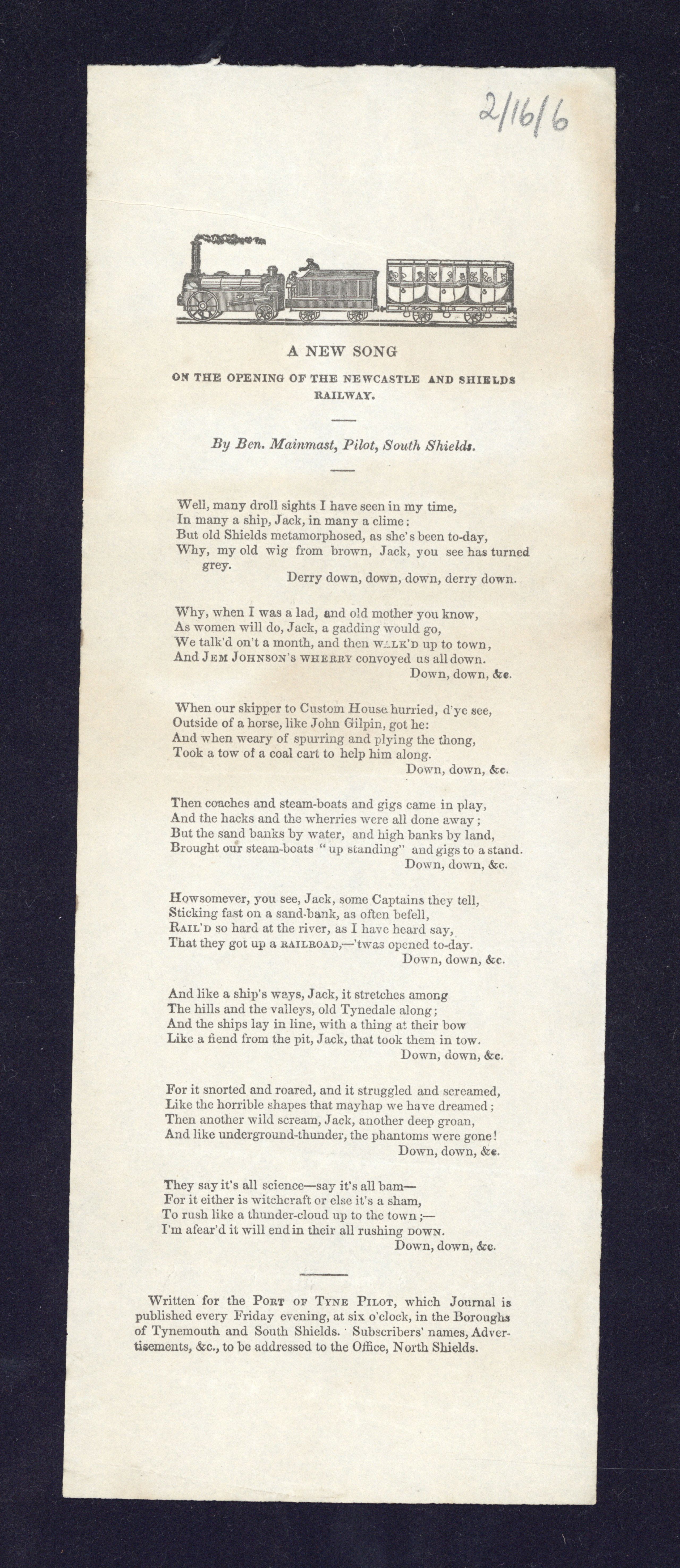

A New Song on the opening of the Newcastle and Shields Railway 1839, Broadsides 2/16/6, Broadsides, Newcastle University Archives, GB 186

This song is typical of broadside ballads and slip songs: it has no musical notation. Often, songs were sung to the tune of other popular (i.e. well-known) songs. The author, Ben Mainmast, is most likely to be a pseudonym. It was written for the Port of Tyne Journal and communicates a sense of displeasure at the transformation of South Shields by the opening of the railway: “But old Shields metamorphosed, as she’s been to-day, / Why, my old wig from brown, Jack, you see has turned grey.”

A Parliamentary Bill proposing a rail link between Newcastle and South Shields failed twice before a modified proposal was passed in 1836. The Newcastle and Shields Railway opened in June 1839 and ran on a standard gauge from a temporary terminus in Carliol Square, Newcastle. The Ouseburn Bridge was built by the company in the 1830s. (The railway infrastructure is now utilised by the Metro.) It rivalled the steam tugs that transported coal – the average speed of express trains around this time was 31-34 mph. The railway was opposed, not only by the rivermen and people connected with the wharves, but also by South Shields’ shopkeepers who feared their customers might be lured into spending their money in Newcastle by cheap fares and short journey times.

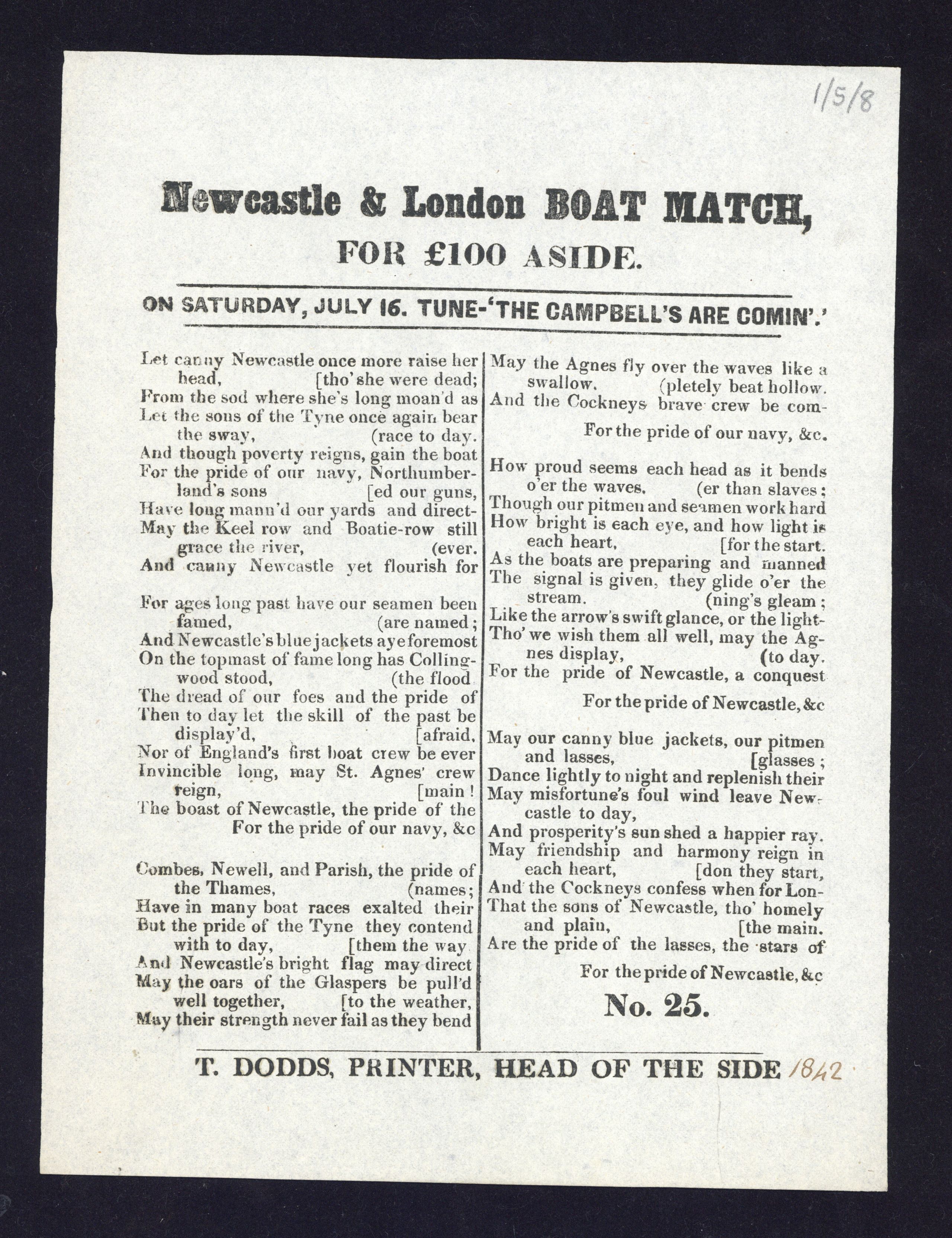

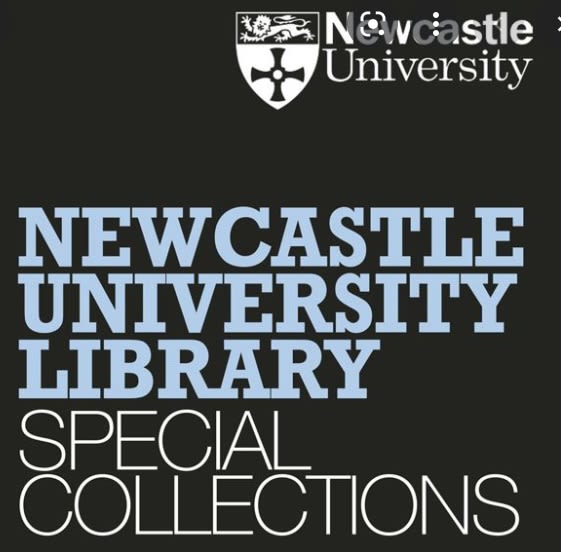

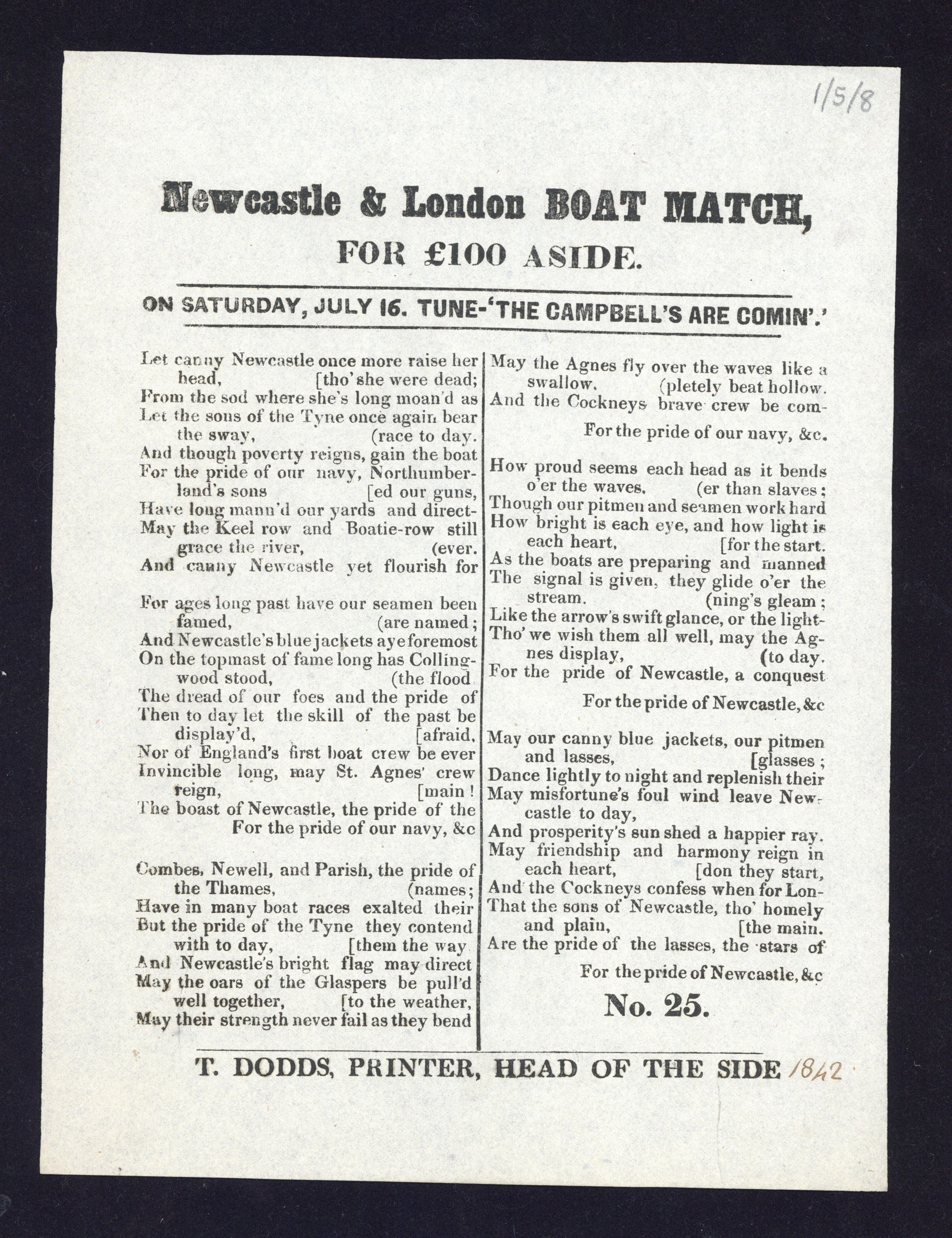

Newcastle & London Boat Match, for £100 aside 1842, Broadsides 1/5/8, Broadsides, Newcastle University Archives, GB 186

Thomas Dodds was a radical printer, printing Chartist broadsides and the Miner’s Advocate. This song therefore seems unrepresentative, or atypical, of his usual printing outputs. Three years after this song was printed, Dodds went bankrupt and his printing equipment was put up for sale but two years later, he was back in business on Grey Street.

The song describes a boat race between Harry Clasper and his brothers and the best rowers from London, on 16th July 1842. Harry Clasper had beaten all the Tyne crews and fancied his chances against the best rowers in the country – the team from London. They raced over a five-mile course from the Tyne Bridge to Lemington, for £100 stake (roughly equating to a little over £6,000 in today’s spending power). Clasper and his brothers were in the St. Agnes but the London team had a lighter boat and took an easy win.

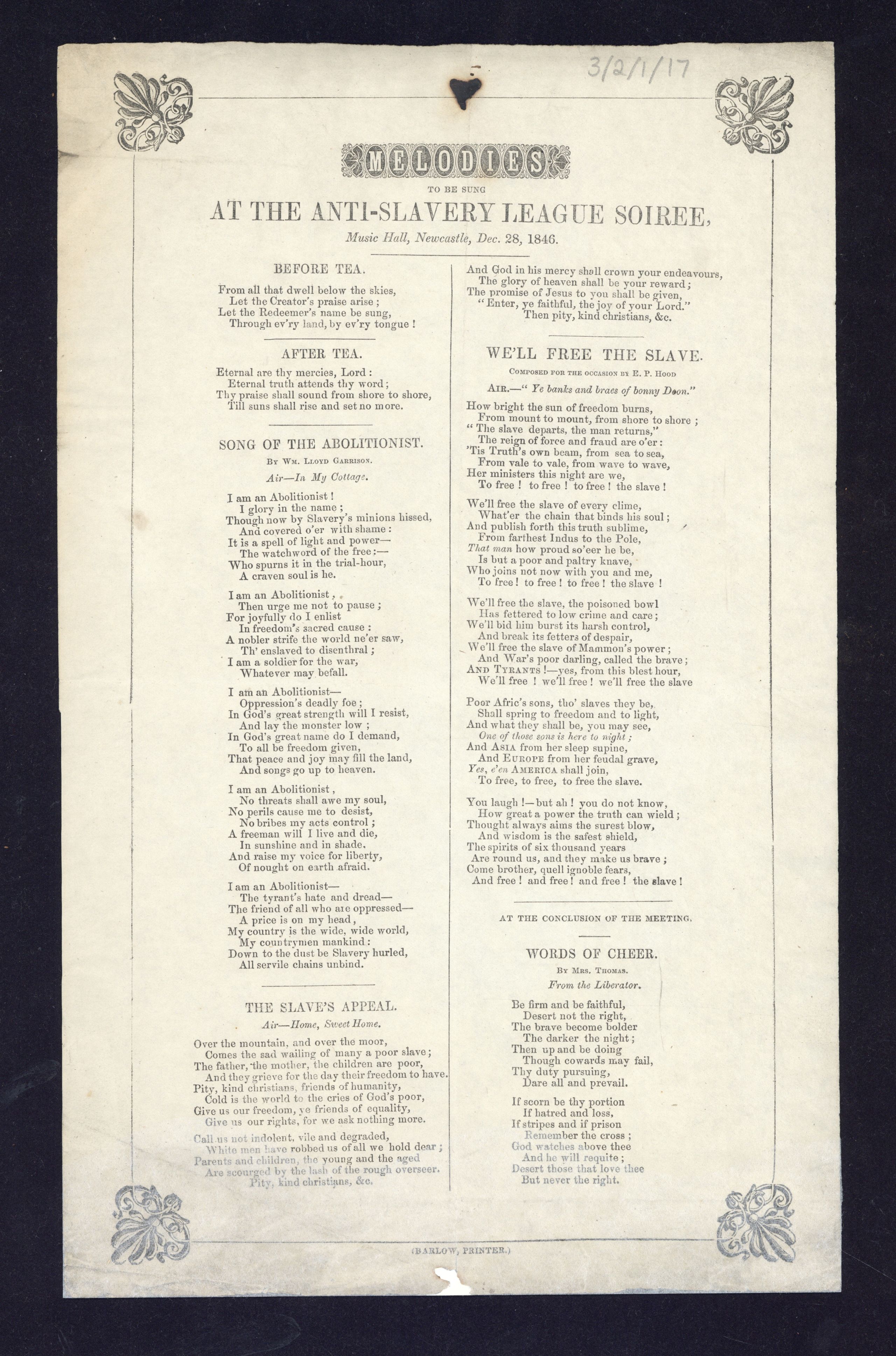

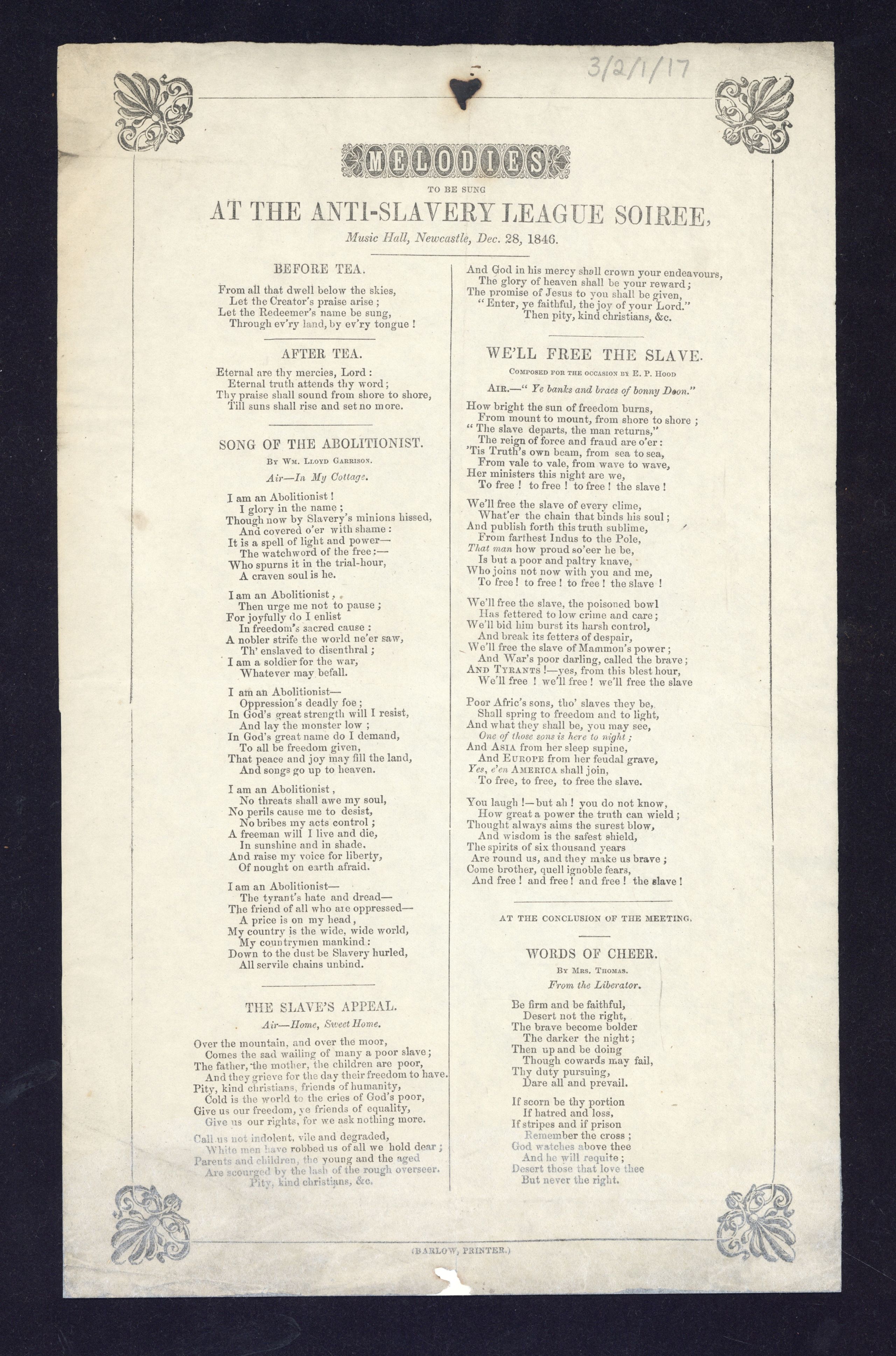

Melodies to be sung at the Anti-Slavery League Soiree, Music Hall, Newcastle, Dec. 28, 1846, Broadsides 3/2/1/17, Broadsides, Newcastle University Archives, GB 186

This broadside is printed with six songs, including ‘Song of the Abolitionist’, ‘The Slave’s Appeal’ and ‘We’ll Free the Slave’. Again, there is no musical notation but the tunes to be borrowed are indicated against some of the songs.

Anna Richardson, her husband Henry and her sister-in-law Ellen welcomed escaped slave, social reformer and leader in the abolitionist movement, Frederick Douglass (1817-1895) to Summerhill Grove, Newcastle (near Newcastle University’s Helix site). They were Quakers and, in accordance with Quaker beliefs, the women were well-educated and active in religious and public life. The assistance they gave to escaped slaves included raising funds to buy Douglass from Thomas Auld, on 5th December 1846.

Newcastle had played a significant role in the abolition of slavery within the British empire; here there was also white working-class solidarity with the abolitionist movements in the United States of America. The Music Hall on Nelson Street was used for lectures, exhibitions, concerts, bazaars and public dinners. It was in a hall on the first floor that Frederick Douglass spoke to a 700-strong audience and thanked Newcastle’s female abolitionists for having financially secured his freedom, on 28th and 29th December 1846.

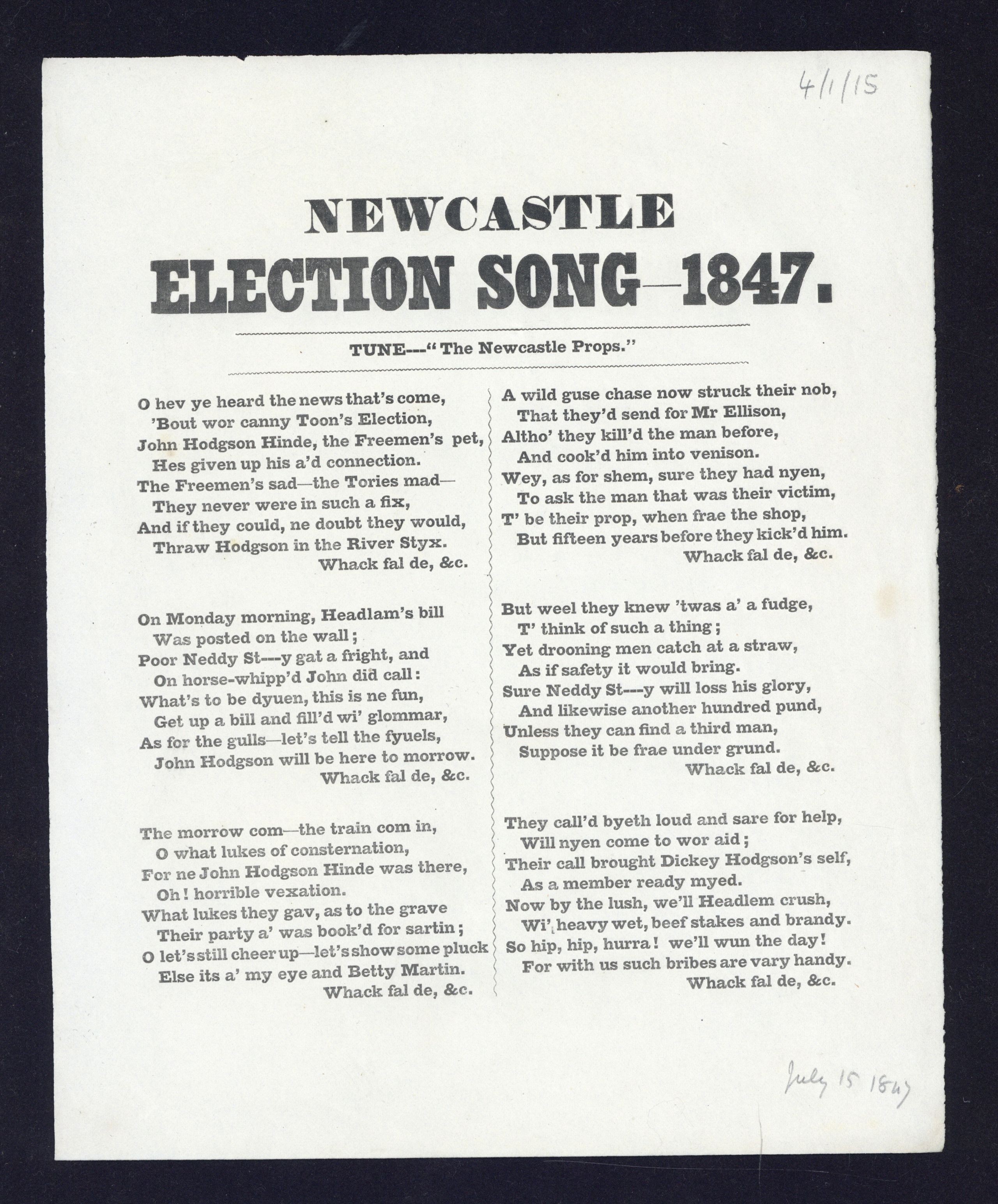

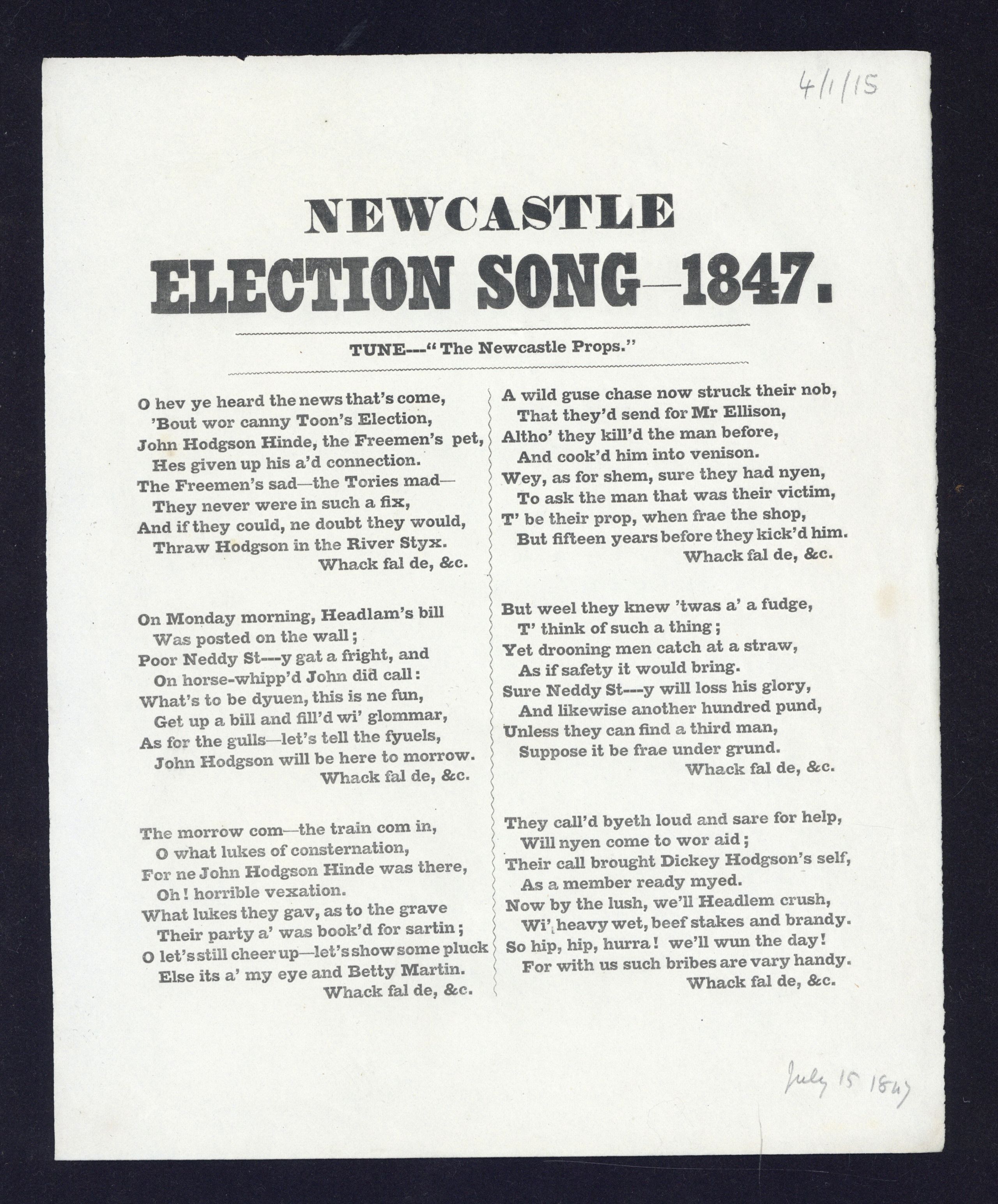

Newcastle Election Song 1847, Broadsides 4/1/15, Broadsides, Newcastle University Archives, GB 186

This election song from July 1847 begins with the suggestion that John Hodgson Hinde has given up. John Hodgson Hinde (1806-1869) was the favourite candidate of the Freemen of Newcastle. He had been returned for Newcastle as a Conservative at the 1836 by-election and retained his seat until 1847. Meanwhile, Whig candidate, Thomas Emerson Headlam (1813-1875), has posted a bill that has rattled the Conservatives: “Poor Neddy St---ey gat a fright”. This refers to Edward George Geoffrey Smith-Stanley (1799-1869) who had previously been known as Edward Stanley. In 1847, Stanley was Leader of the Conservative Party.

In need of a new candidate, there’s an idea to call on Mr Ellison. Cuthbert Ellison (1783-1860) had stood down at the 1830 General Election. Described as drowning men clutching at straws, Ellison is now unelectable – likely to lose glory and his £100. Enter “Dickey Hodgson”, or, Conservative Richard Hodgson who, it is hoped by the author, will crush Headlam. (It wasn’t to be: the Whigs won in Newcastle and the General Election.)

The final verse talks about bribes. At this time, there was no secret ballot; voting was public and open to corruption. A practice called ‘treating’ continued into the late-Nineteenth Century – influencing voters with alcohol and food: “Wi heavy wet, beef stakes and brandy”. (The 1832 Reform Act had enfranchised some middle-class men who met a property qualification but working-class men and all women were excluded from the electoral process.)

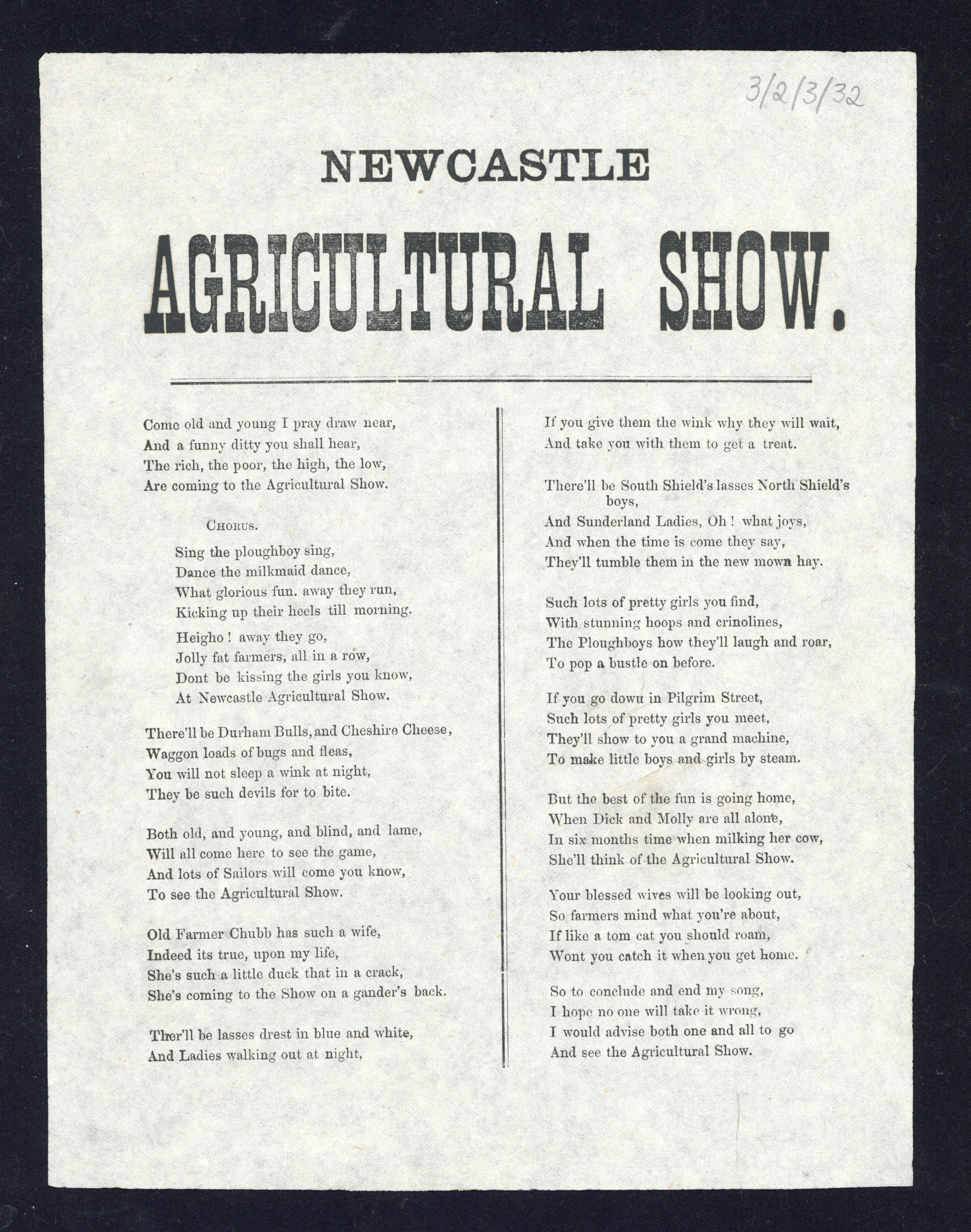

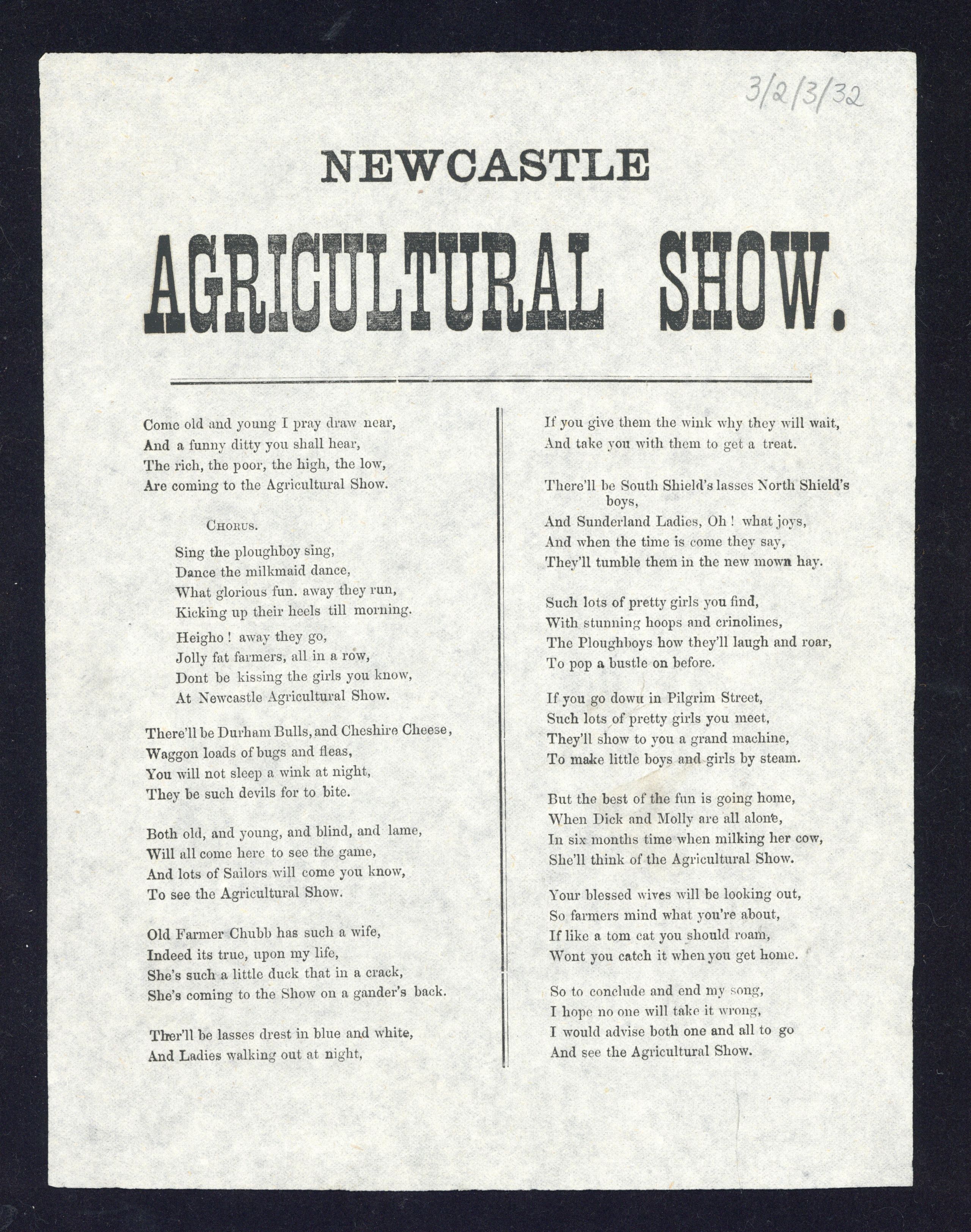

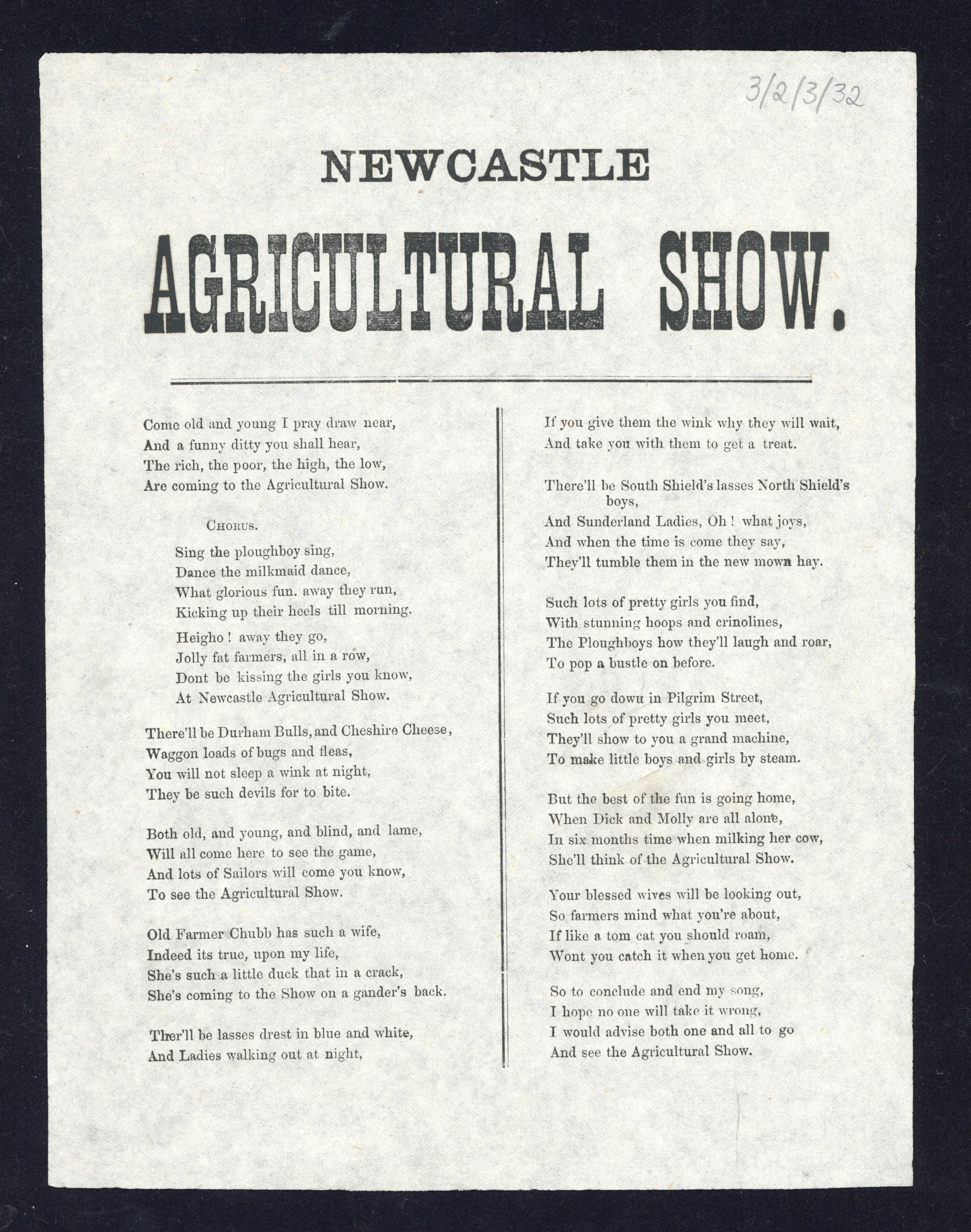

In the early-Nineteenth Century, many of the townships that would become part of Newcastle, such as Elswick, were rural areas comprising farms and fields. Farming changed dramatically in the 100 years leading to the mid-Nineteenth Century, with open fields being enclosed and industrial innovations improving production levels. Look at historic maps of Newcastle and the surrounding areas and you will see windmills; Newcastle opened its cattle market in July 1830 (on the site now occupied by the Centre for Life); Jesmond Vale comprised pasture, woodland and a mill on the Ouseburn; and the Newcastle Chamber of Agriculture and Farmers’ Club (established in 1843) occupied a room in the Town Hall building off the Corn Exchange. It seems a little unfair, then, that The Times snootily described Newcastle as “a land of coals – where vegetation above ground is of slight value compared with the vast geological forests fossilized in seams and mains beneath” on the occasion of the Royal Agricultural Society of England holding it’s show here in 1864.

Newcastle Agricultural Show c.1864, Broadsides 3/2/3/32, Broadsides, Newcastle University Archives, GB 186

Agricultural shows were important dates in the rural social calendar. This broadside song calls to people of all ages and backgrounds to travel to the show, even from North and South Shields and Sunderland. There isn’t much about agriculture or farming in the song: it depicts the show as a place to have fun, for dancing, frolicking with the opposite sex and making memories.

Mining engineer and land surveyor, Thomas Sopwith (1803-1879) attended the Newcastle Agricultural Show in July 1864 and describes it in his diary:

The admission to the Royal Agricultural Society’s show was ten shillings on Monday – and two shillings and six pence on Tuesday and Wednesday – Today it is one shilling and its gates are thus open to the “million” as the current phase is. And truly the million seem to know and appreciate the arrangement. As early as five oclock the streets in the direction of the show were thronged with visitors and the numbers continued to increase during the morning and forenoon. The weather was favourable until near noon when it became somewhat gloomy and some showers of rain fell during the afternoon. In all there were about 5600 visitors to the Show grounds – a number which has only been exceeded on similar occasions, at Leeds.

Across several days, Sopwith enjoyed seeing “a fine collection of horses exercised in a large open space”, a poultry show, his first ever dog show and a flower show. He muses that the people of Shields and Sunderland are maritime, not land, people and therefore the high attendance was even more remarkable. Indeed, it is the crowd that he went to see more than the objects at the show:

Truly it was a most marvellous sight to see so vast an assemblage and it was as pleasing as it was wonderful. Every one there had, it may be fairly presumed come there either to examine some select objects in which they were interested – or to view the general display – or it may be that to enjoy a holiday and to meet their friends might be upper-most in their minds.

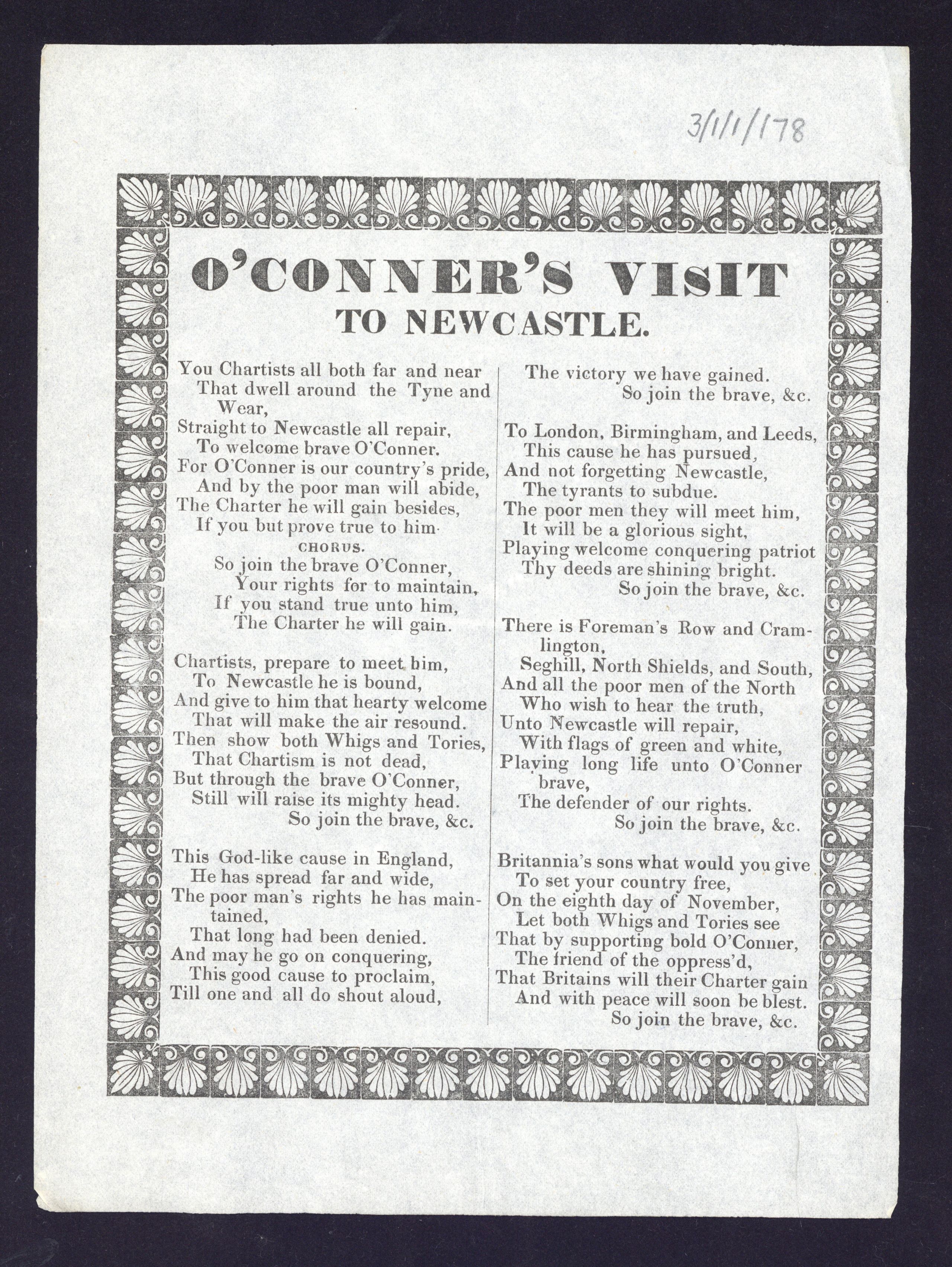

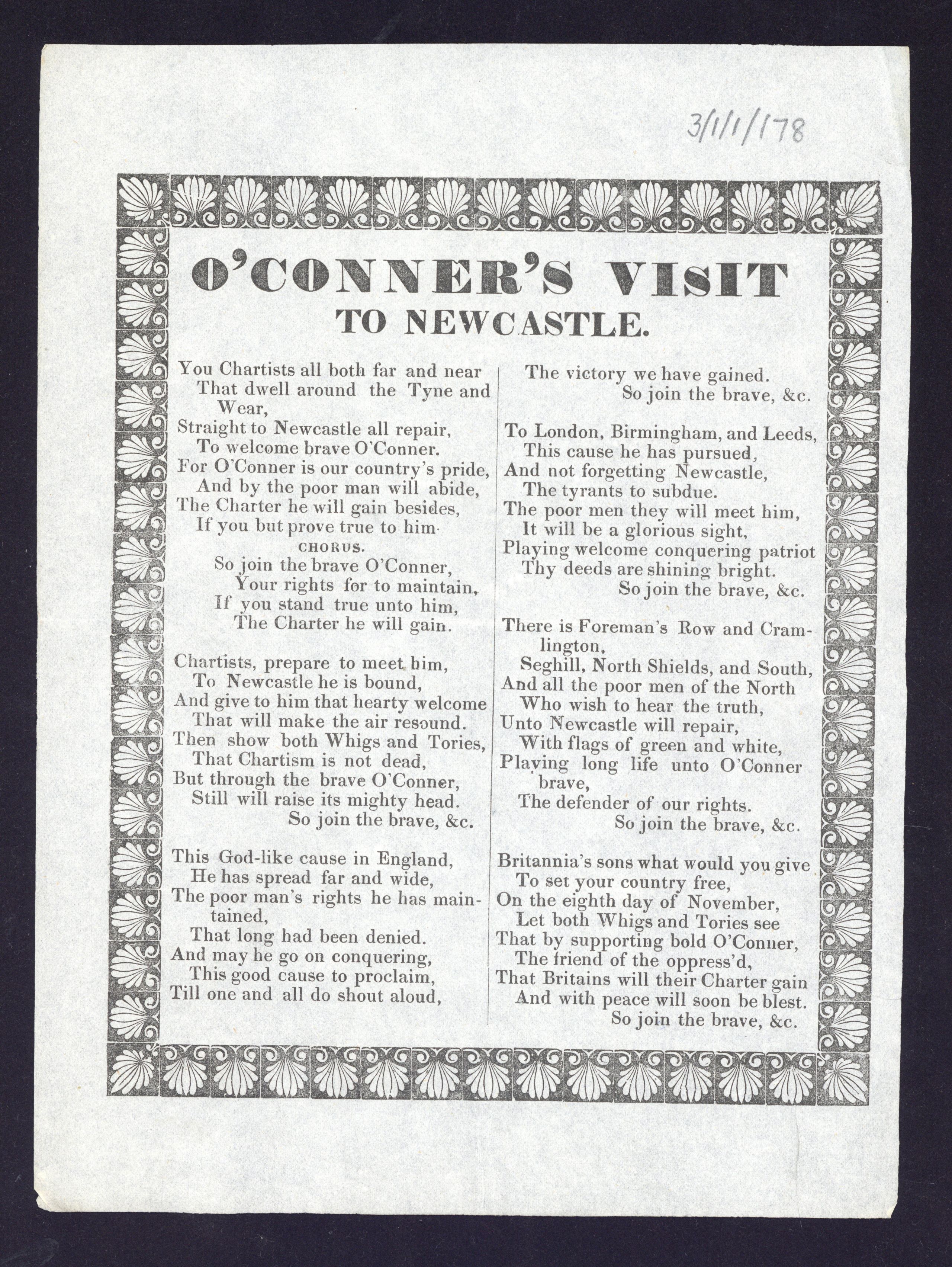

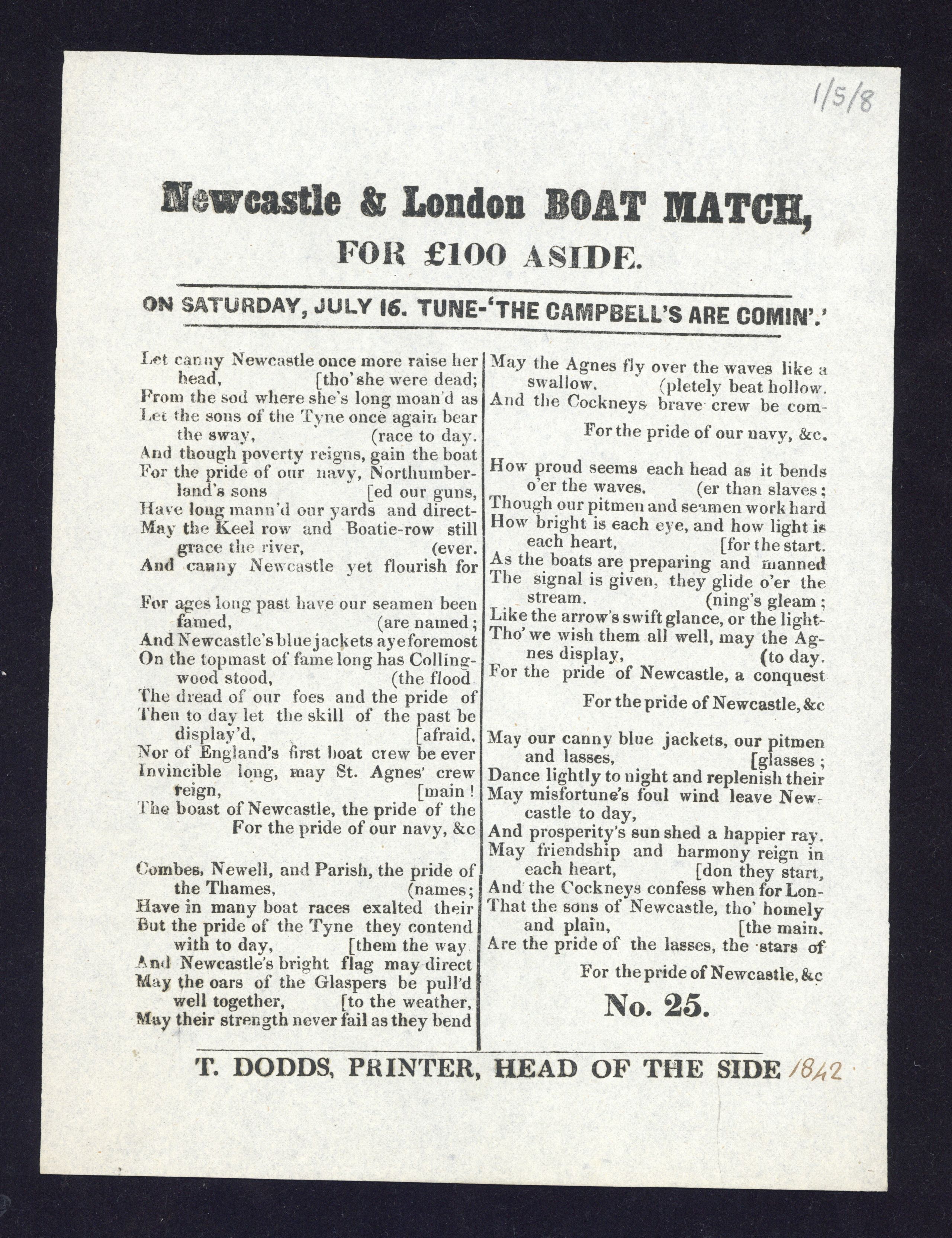

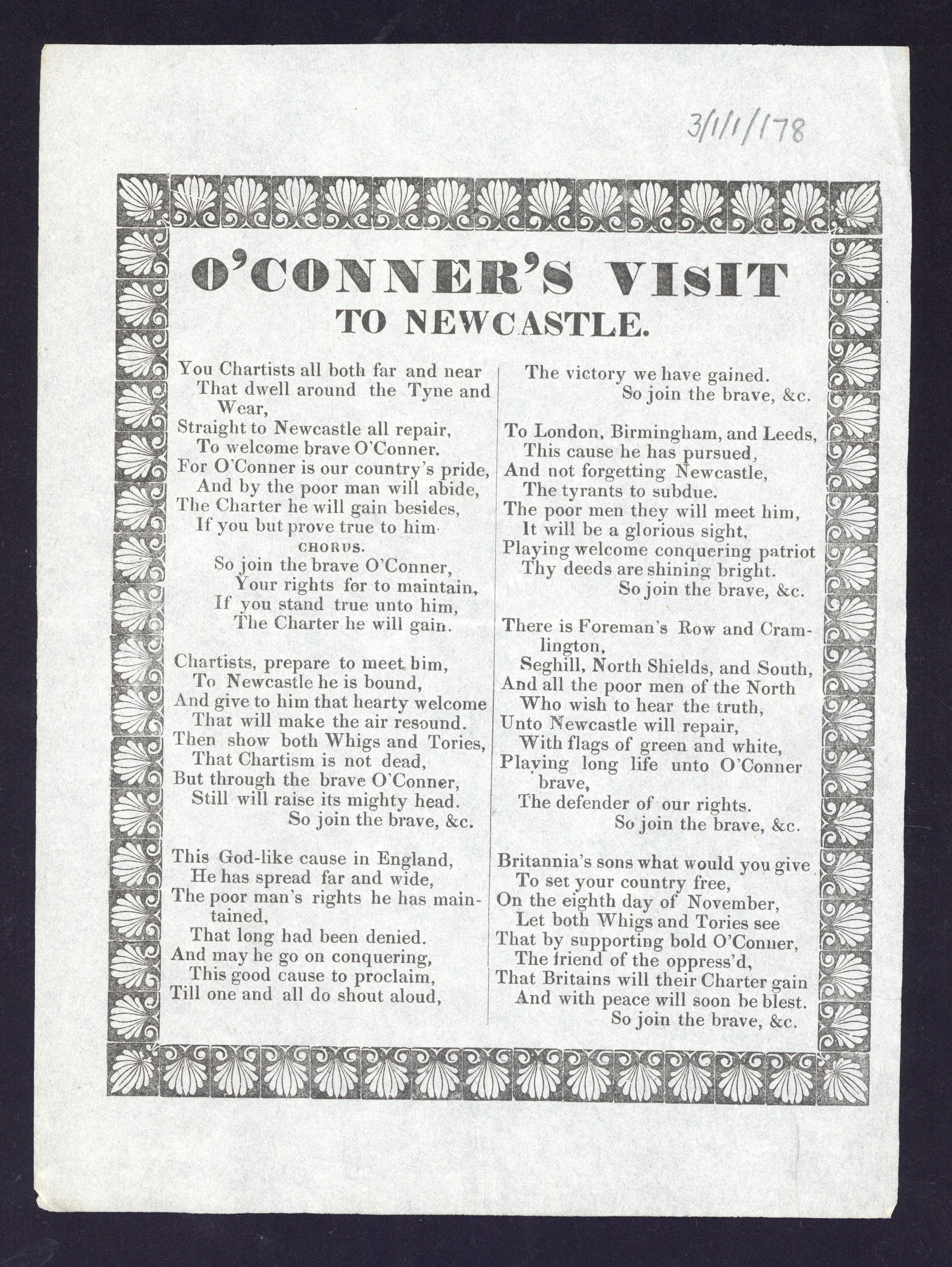

O'Connor's Visit to Newcastle 1800s, Broadsides 3/1/1/178, Broadsides, Newcastle University Archives, GB 186

This broadside is undated and there is no imprint information that would allow us to investigate the printer. However, it was most likely to have been printed in the early- or mid- 1840s. The O’Connor of the title is Feargus O’Connor (1796-1855), a leader of the Chartist movement. It seems, from the song, that he is due to visit Newcastle upon Tyne on 8th November. O’Connor had visited Newcastle previously, when he had given speeches about parliamentary representation on the Town Moor, to crowds of 70,000 and more. His audiences were made up of local tradesmen, working-class men who came together from Newcastle and outlying villages such as Winlaton.

The demands of the Chartists came to be known as The People’s Charter and included: universal male suffrage; secret ballots; annual general elections; and the removal of property qualifications for MPs. It was a national movement that took a strong hold in the working-class communities of the North East. Chartism did not actively advocate women’s suffrage, but neither were Chartists opposed to it and the movement had female support, with women attending Chartist rallies.

Find out more:

This virtual exhibition was brought to you by Newcastle University Library Special Collections & Archives.

To find out more about Newcastle University Library Special Collections & Archives holdings please Browse our Collections.

To discover how you can consult materials please see Using our Collections.