Children and Chapbooks:

A Middle Modern Encounter

A Virtual Exhibition by Elisa Marazzi and

Newcastle University Special Collections

Introduction

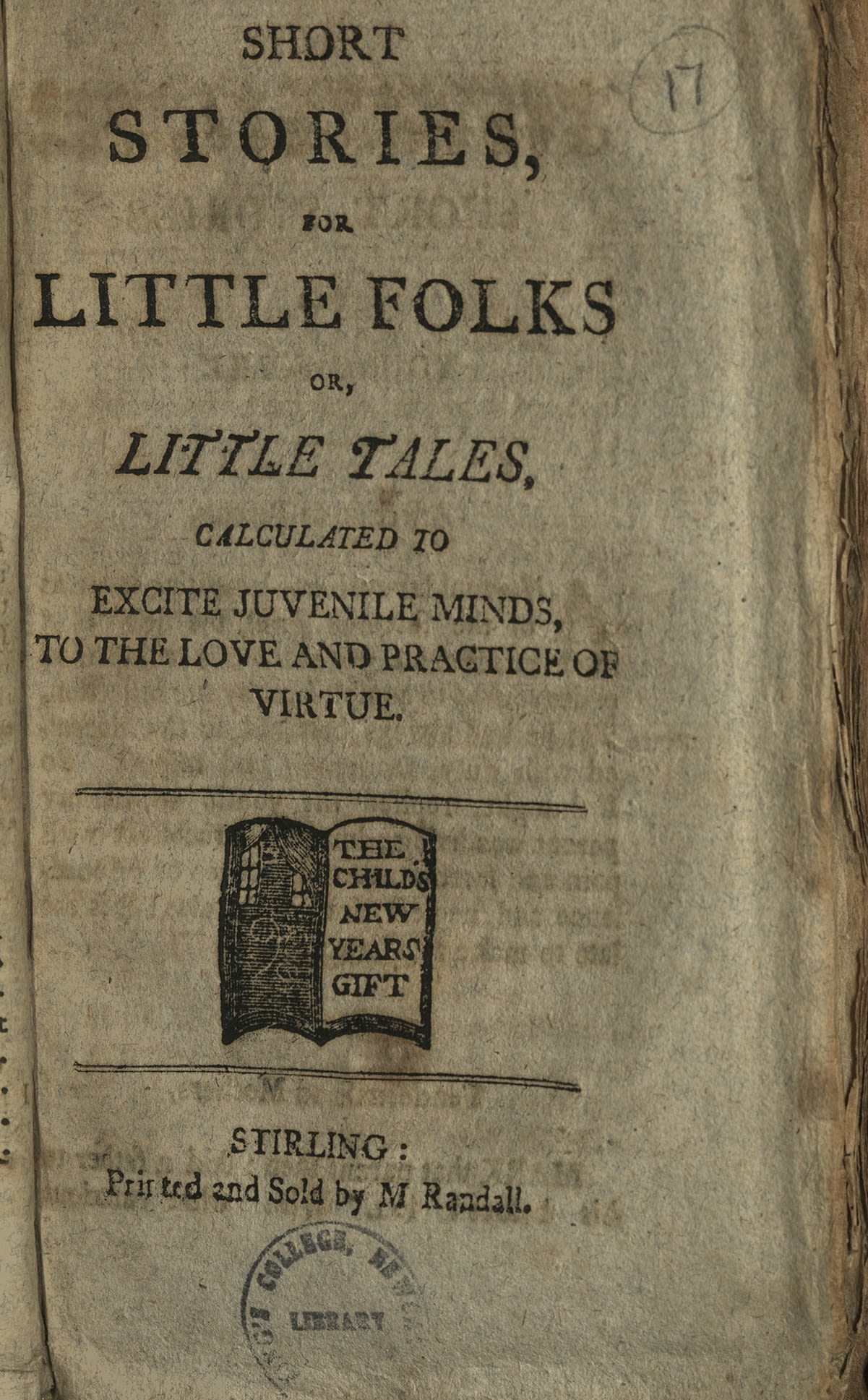

Short Stories, for Little Folks or, Little Tales, calculated to excite juvenile minds, to the love and practice of virtue, 1800-1899, Chapbooks 821.04 SUR(17), Chapbooks, Newcastle University Special Collections, GB 186.

Children have always enjoyed reading and looking at pictures, but many did not have access to recreational books designed for them until the nineteenth century. This exhibition reveals that chapbooks, a form of popular print largely available across Britain, were often a good substitute, so that some publishers even started to issue newly designed “children’s chapbooks” in the early nineteenth century.

Together with broadside ballads, chapbooks were popular printed items in early modern Britain. One reason for that was that they were cheap. As paper made up a high portion of the cost of a book, to keep the price low they had few pages, usually twelve or twenty-four; the fixed number was due to the printing and binding process (but chapbooks with more or fewer pages also existed). They looked very unrefined, the title page served as cover and was often the only illustrated part of the book. Illustrations were printed through woodblocks, often reused from previous publications by the same or other printers. The contents, usually anonymous, were extremely varied: from tales of romances to riddles, from pious materials to ballads and songs, from books of jests to horrific executions.

Chapbooks were already circulating in the seventeenth century: some of them survive thanks to one notable early collector, the diarist Samuel Pepys (1633-1703). Those printed in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries have bigger survival rates. For this timeframe, a sizeable number of reading testimonies, combined with inscriptions, archival records, and other evidence allows us to argue that children were among the audience of chapbooks. To the modern reader, the idea of children enjoying these flimsy – and often dull-looking – booklets could sound bizarre. But the items showcased will reveal that children were surely a fond audience, and therefore printers increasingly addressed them.

The exhibition features a small selection of the chapbooks preserved in the Chapbooks collection, many of which were formerly owned by the antiquarian Robert White (1802-1874). Over 1600 chapbooks, including those with content that children could relate to, are available to researchers through the Reading Room. Other historical books for children, printed in the eighteenth century or earlier, are also available in the Brian Alderson collection.

The Chapbooks

Robin Hood is a typical chapbook title: a tale well-known by everyone, that had circulated for centuries both orally, manuscript and in printed books. In chapbooks such tales were often retold in verses: rhymes are pleasant to read aloud and to be listened to. The stories could also be sung.

The life and death of Robin Hood, The Renowned Out-law. And the famous exploit performed by him and little John, 1800-1899, Chapbooks 821.08 WAG, Chapbooks, Newcastle University Special Collections, GB 186.

This chapbook has a peculiarity: on page 9 one woodcut is printed upside down. This might have happened due to the necessity to issue many copies in a short time. The process was manual, and the compositor who prepared the printing matrix could make mistakes and place an element badly. Yet the production costs had to be kept low, hence wasting paper, ink and time was impossible. Chapbooks were not meant to look accurately printed, therefore an edition with this kind of defect could easily be sold.

Woodcut from The True Tale of Robin Hood, 1800-1899, Chapbooks 823. REN, Chapbooks, Newcastle University Special Collections, GB 186.

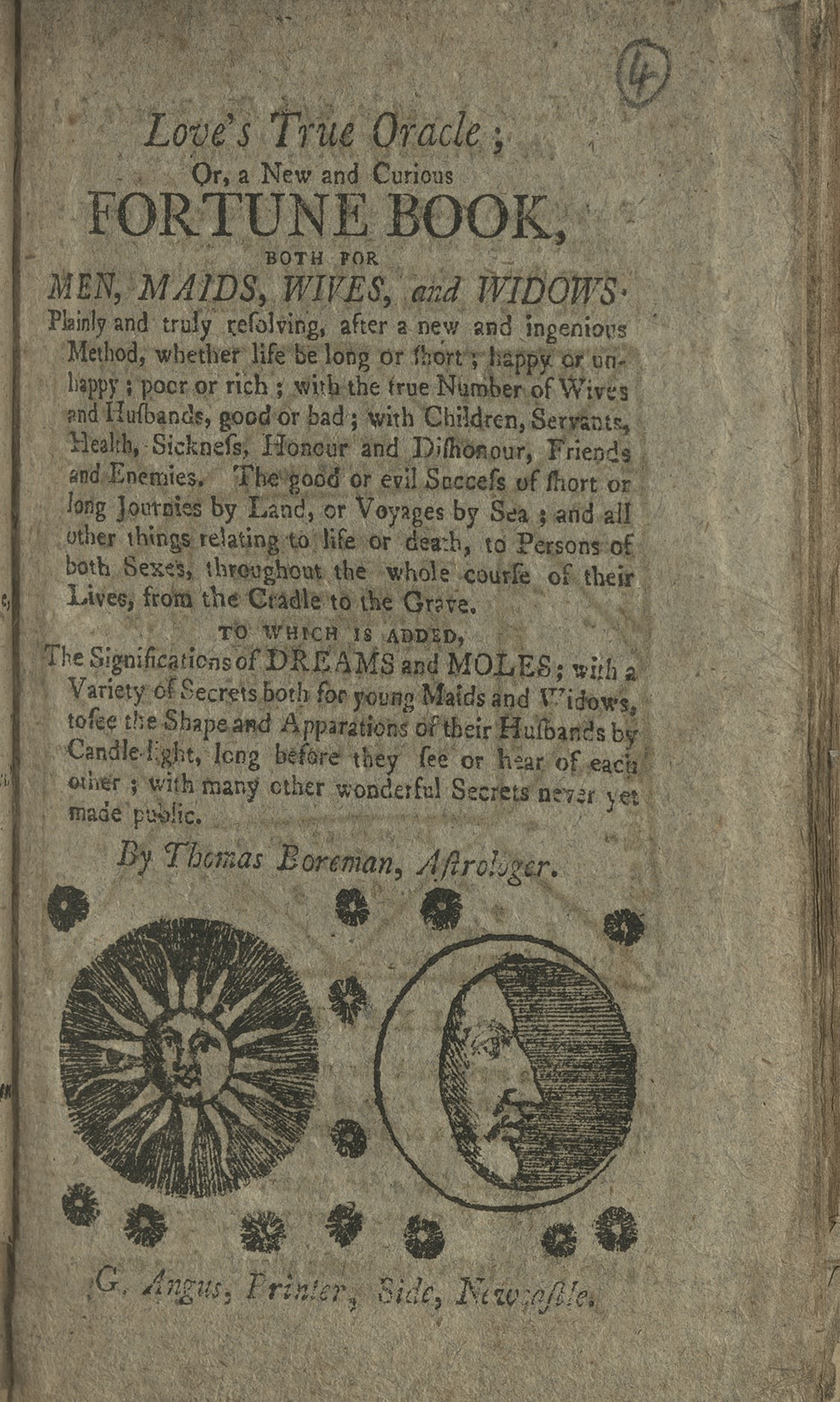

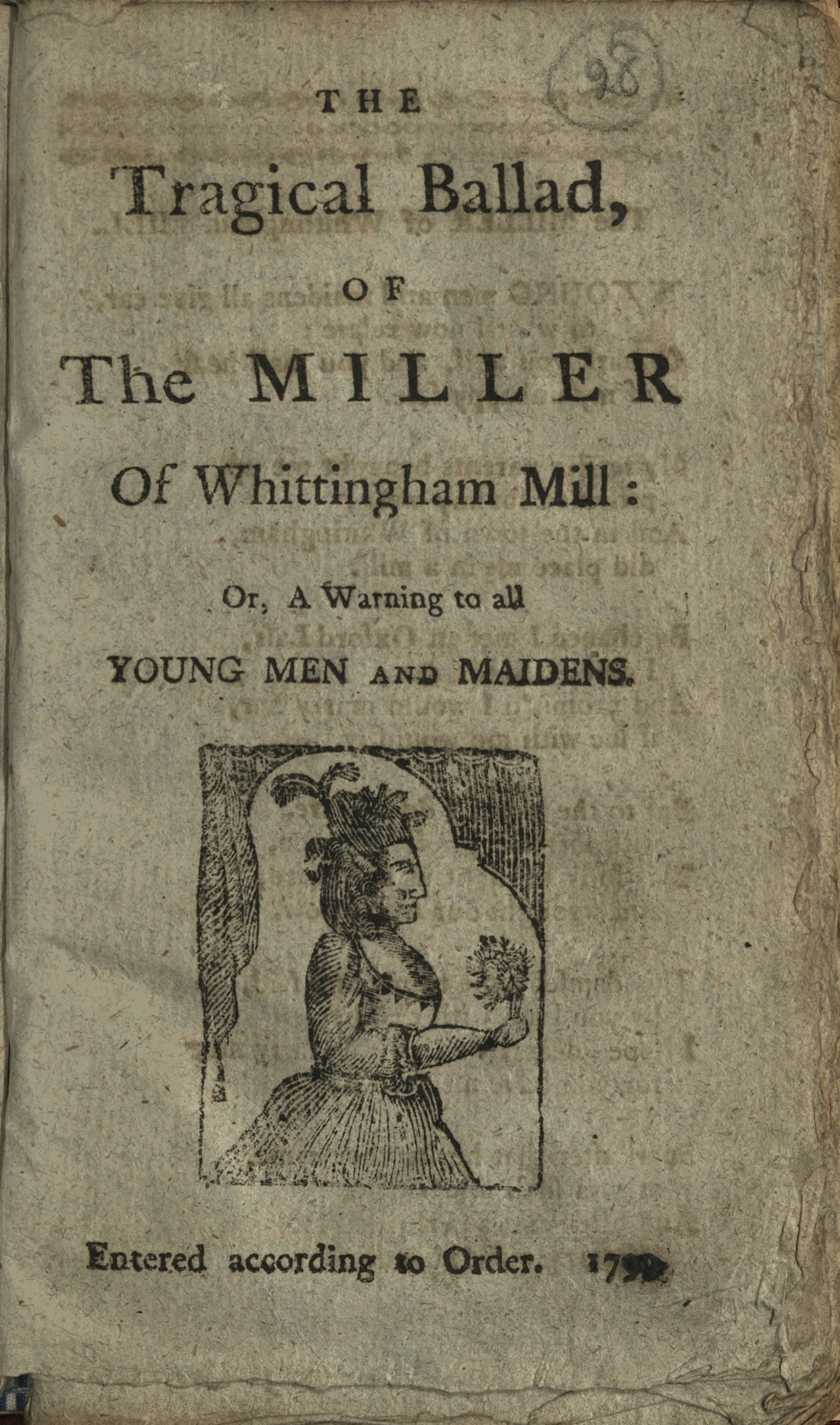

These two chapbooks, containing a fortune telling book and a ballad, are typical items of popular print of the past. Interestingly, they explicitly address their possible audience and include young people in it, although the contents were not particularly adapted to a specific readership.

Love's True Oracle; Or, a New and Curious Fortune Book, 1800-1899, Chapbooks 821.89 GAR (4), Chapbooks, Newcastle University Special Collections, GB 186.

Chapbooks circulated widely in the society and therefore they were familiar to children as well as to adults. When stories were addressed to young people it was often the case that they included some form of moral education. In the Tragical Ballad, of The Miller Of Whittingham Mill a young man commits tragical crimes as he does not want to take the responsibility to marry a young lady pregnant with his child. It is easy to understand how this could be meant as an exhortation to readers to take full responsibility for their actions.

The Tragical Ballad, of The Miller of Whittingham Mill: Or, A Warning to all Young Men and Maidens, 1799, Chapbooks v. 13(28), Chapbooks, Newcastle University Special Collections, GB 186.

Chapbooks (as well as broadsides) could also contain the so called “gallows literature”: biographies, “last speeches”, and “dying verses” of people condemned to death. People were curious to read about those events or to listen to their narrations, and printers worked hard to satisfy their audiences’ appetite. For the modern reader it could be problematic to accept that children were exposed to such texts, but they were exposed to public executions as well. In this example a double aim is pursued: narrating a sensational gallows story, but also, again, warning readers that not complying with the norms of the society could result in serious punishment.

A Dreadful Warning to Disobedient Children, 1800-1899, Chapbooks v. 36 (29), Chapbooks, Newcastle University Special Collections, GB 186.

Sometimes inscriptions help librarians and book historians to understand something more about the history of an item. In this chapbook we find an unusual inscription: it was made by someone who was learning to write. We cannot be sure that this was necessarily a child, as in the past people could have access to different forms of literacy in different stages of life. However, it is interesting to see this chapbook, containing songs, used as a copybook, a type of books produced for learners to practice their handwriting by copying letters and words proposed as models. Among many chapbooks that addressed children, we find a possibly juvenile inscription in a book of songs, not specifically addressed to a particular audience. This is a reminder that, no matter the publishers’ or authors’ expectation, people were and are free to read what they wish: any reader might go astray from instructions provided by publishers as well as other gatekeepers.

Six excellent new songs, 1806, Chapbooks v. 12(6), Chapbooks, Newcastle University Special Collections, GB 186.

Aladdin or the Wonderful Lamp

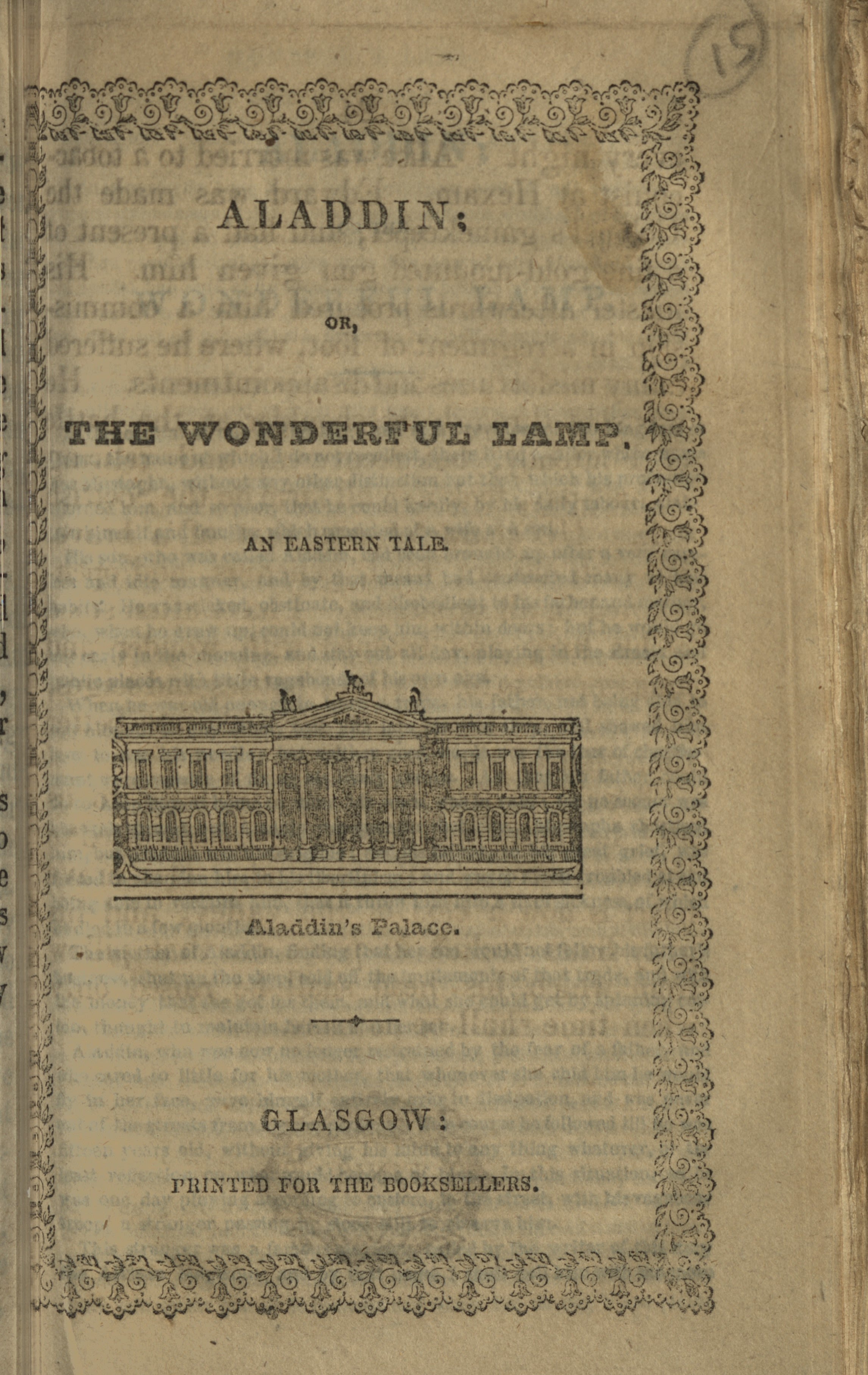

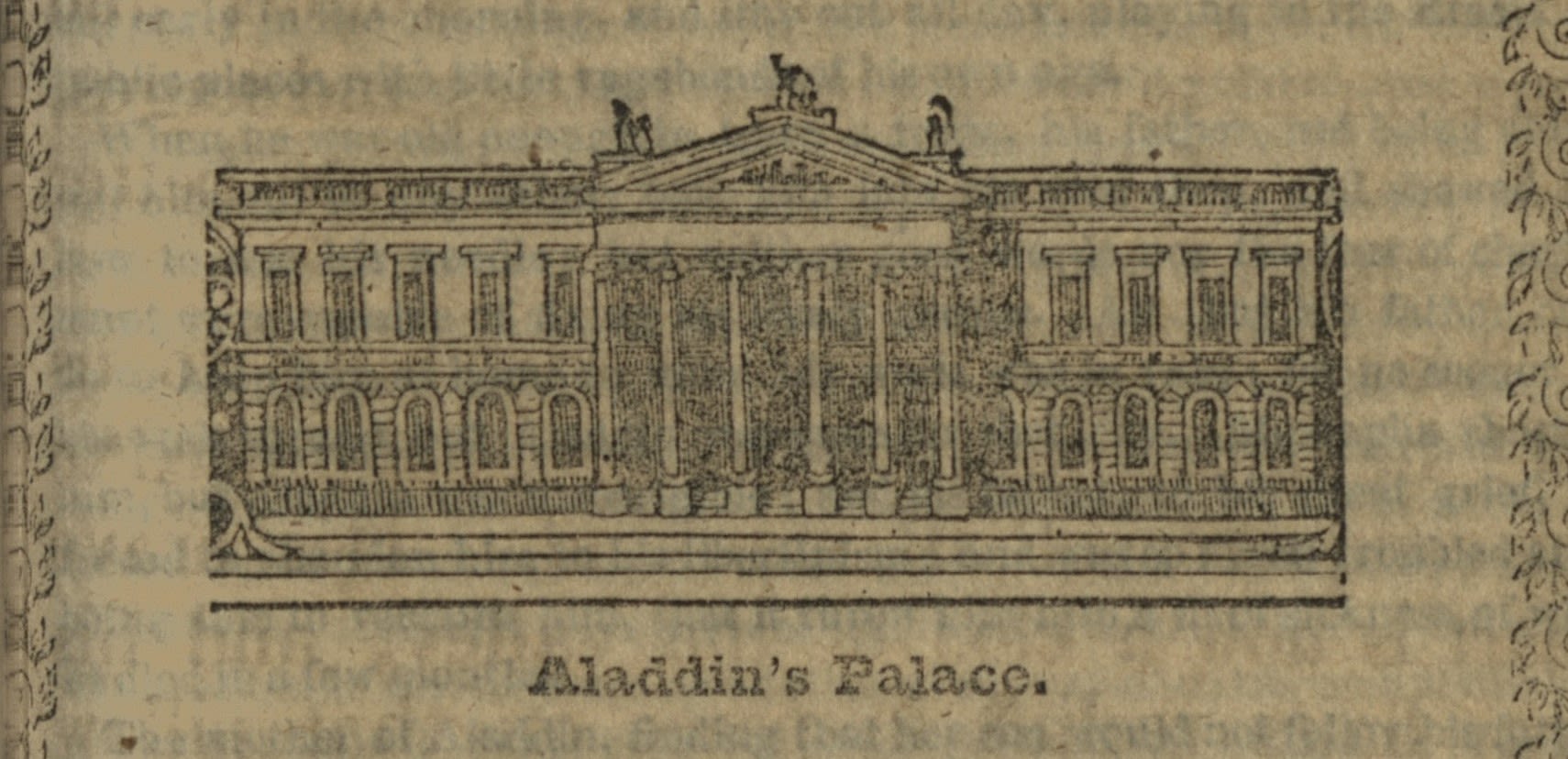

Tales that are now intended as juvenile were enjoyed by a large audience of adults and children. As well as Robin Hood, the story of Aladdin circulated orally both before and after being fixed on the page in manuscripts and printed volumes. Aladdin is among the “gripping tales” that Hugh Miller (1802-1856) found in chapbooks as a boy. Miller later wrote an autobiography focused on his studies, where he mentions he enjoyed chapbooks after having learnt to read the scripture, and before passing over to more complex texts (Hugh Miller, 'Schools and Schoolmasters', p. 28-30).

This example is also interesting for the illustration on the title page. Aladdin’s Palace is represented as a typical Western eighteenth-century building, nothing to do with the ‘Eastern tale’ advertised. Again, this can be explained with the choice to keep costs low: woodblocks were not produced specifically for a certain chapbook, but they were reused from the publishers’ stock. Moreover, we cannot guess what contemporary readers would have expected as a depiction of an “Eastern” palace.

Aladdin; or, The wonderful lamp. An eastern Tale, 1800-1899, Chapbooks v. 40 (15), Chapbooks, Newcastle University Special Collections, GB 186.

Mother Goose's Fairy Tales

The origins of the character Mother Goose are to be retraced in late seventeenth-century France, where Charles Perrault, one of the initiators of the literary fairy tale genre, published a collection of stories previously handed down orally between generations. The collection was known under the title Contes de ma mère l'Oye [Tales of My Mother Goose]. Soon after it was translated into English and, like in France and other European regions, it circulated in editions faithful to the original as well as in cheap abridgments. The latter were not initially aimed at children, although probably enjoyed by old and young, as stated in the title page of this chapbook: "Here Mother Goose in Winter Nights, The old and young she both delights". John Clare, an agricultural labourer born in 1793, learned to read from chapbooks like Cinderella, Little Red Riding Hood, and Jack and the Beanstalk (source: RED Reading Experience Database).

The tales included in this example were five of the eight from Perrault’s collection. Interestingly, the stories fixed on paper by Perrault were later separated and they increasingly gained success, becoming the internationally renowned classics of children’s literature that we still read and enjoy. The name of Mother Goose was soon detached from them, and in England it started to be associated with nursery rhymes from the 1780s.

Sleeping beauty, another tale from Perrault’s collection, was probably the inspiration for this nineteenth-century chapbook printed in Glasgow.

Mother Goose's Fairy Tales; containing, I. Little Red Riding Hood. II. Blue Beard. III. Cinderilla; or, The Little Glass Slipper. IV. Master Cat; or, Puss in Boots. V. The Fairy, 1817, Chapbooks 823.4 REN(27), Chapbooks, Newcastle University Special Collections, GB 186.

The Sleeping Beauty of the Wood. An entertaining tale to which is added Paddy and the Bear. A true story, 1800-1899, Chapbooks v.39(4), Chapbooks, Newcastle University Special Collections, GB 186

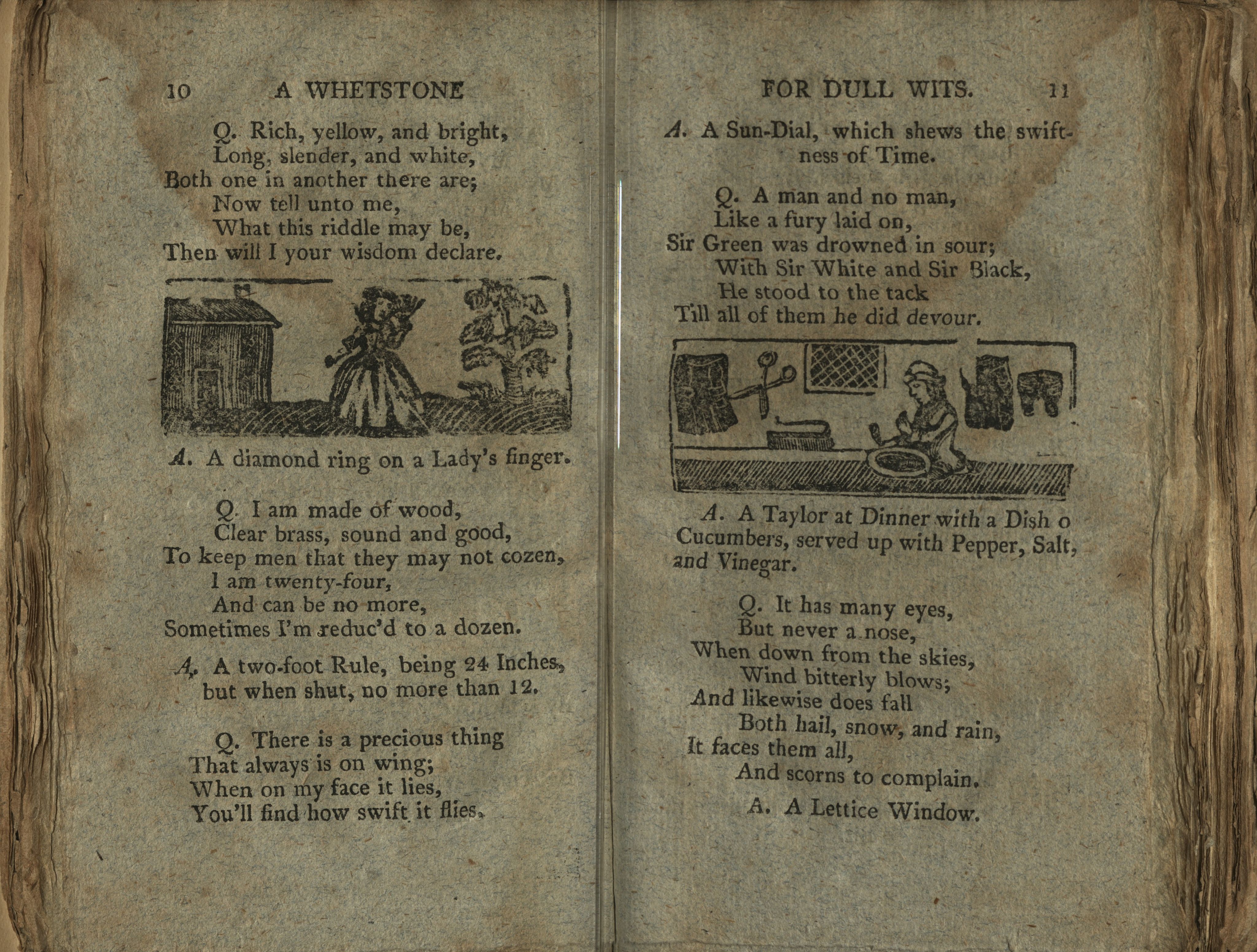

A Whetstone for Dull Wits

A Whetstone for Dull Wits; or, A New Collection of Riddles, for the Entertainment of Youth, 1800-1899, Chapbooks 821.04 JOE(5), Chapbooks, Newcastle University Special Collections, GB 186

Books of riddles were another type of traditional chapbook. In the nineteenth century, traditional purveyors of chapbooks more deliberately adapted their traditional titles to juvenile audiences. Besides mentioning young readers in the title, this chapbook offers them what was intended as suitable for children: the riddles were meant to teach some notions in a pleasant way, and the chapbook had more woodcuts than usual to attract and engage the readers.

Woodcuts from A Whetstone for Dull Wits; or, A New Collection of Riddles, for the Entertainment of Youth, 1800-1899, Chapbooks 821.04 JOE(5), Chapbooks, Newcastle University Special Collections, GB 186

Elizabeth Wrather, a young girl born in 1766, hid a bundle of chapbooks in the chimney of her cottage. Among them there was a book of riddles entitled A Whetstone for Dull Wits. It was printed earlier and was similar, but not the same as this one. The bundle was found by renovators some years ago. It contained common chapbooks that would have been familiar to the general public in the eighteenth century. During Elizabeth’s infancy new books for children were being printed in London, but Elizabeth was living in a small community in Yorkshire and probably had no access to them. This must be why she was so fond of chapbooks that she wanted to preserve them as a treasure. And also why publishers of chapbooks, often active in the provincial trade, started to address children more explicitly in their publications. (Jonathan Cooper, ‘The Development of the Children’s Chapbook in London’. In Street Literature of the Long Nineteenth Century: Producers, Sellers, Consumers. Ed. by D. Atkinson and S. Roud. Newcastle upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2017).

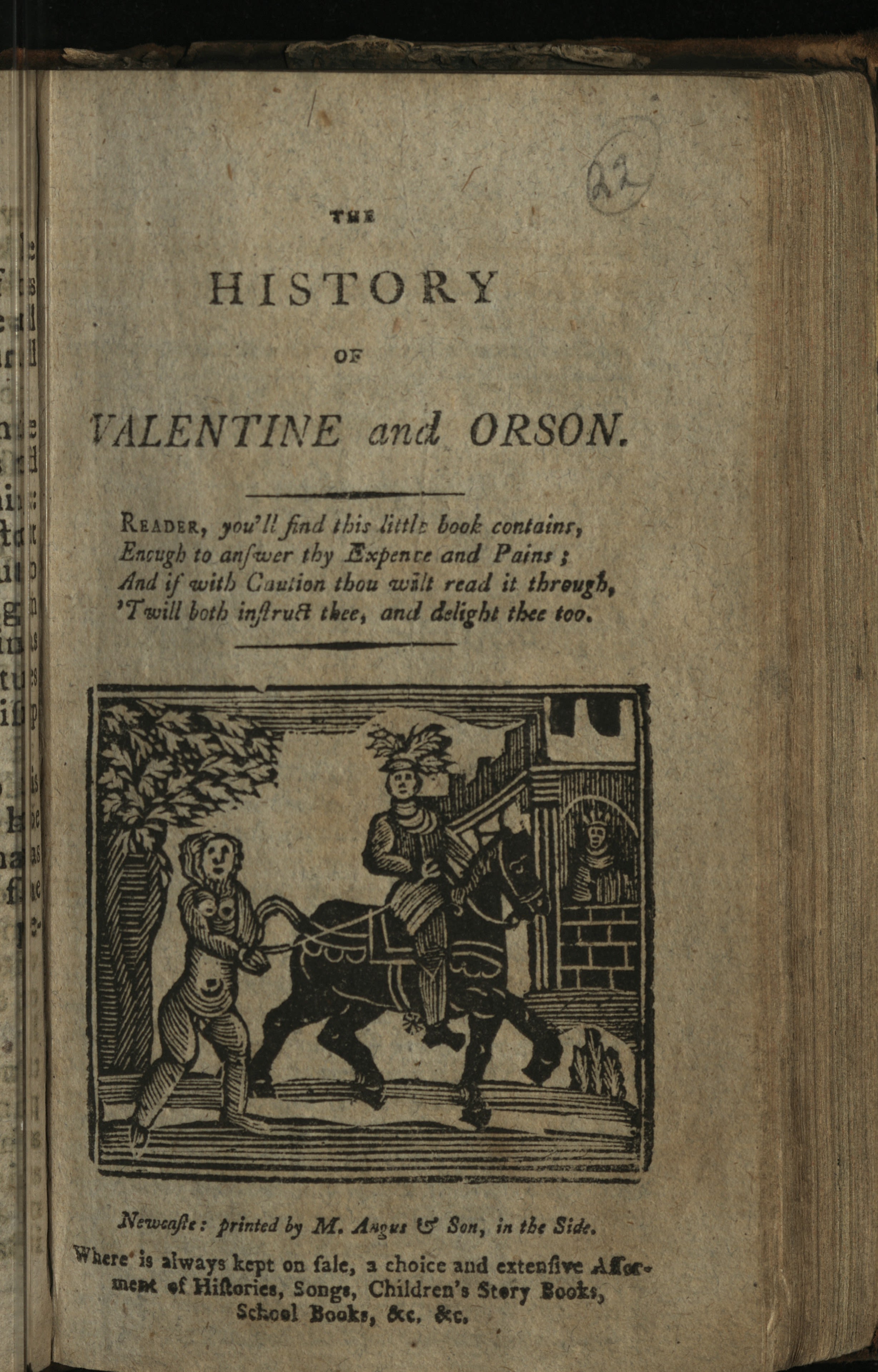

The History of Valentine and Orson

The History of Valentine and Orson, 1800-1899, Chapbooks

Chapbooks v.33(22), Chapbooks, Newcastle University Special Collections, GB 186

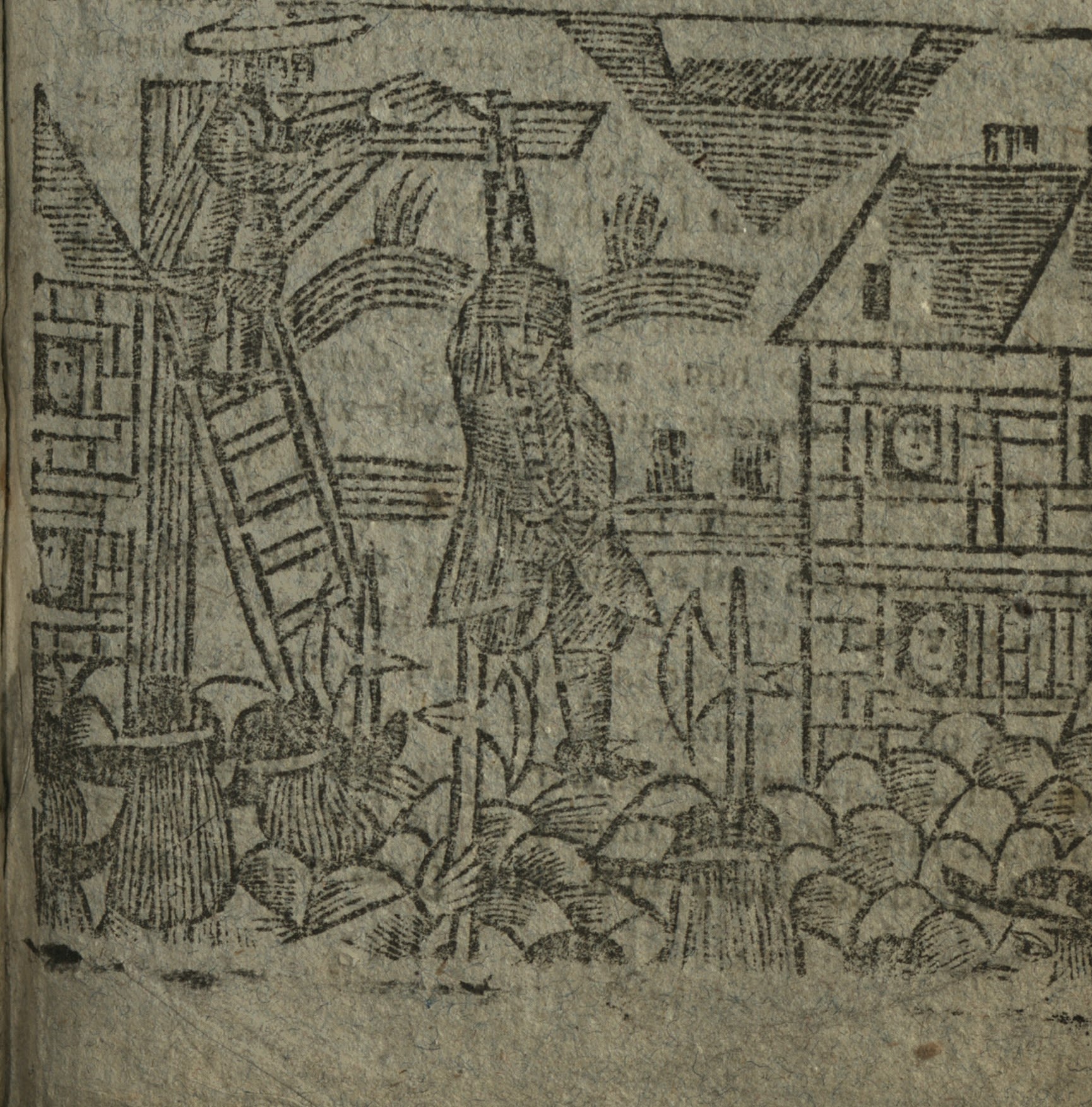

Valentine and Orson is the story of twin brothers, abandoned in the woods in infancy. Valentine is brought up as a knight at the court of Pippin, while Orson grows up in a bear's den to be a wild man of the woods, until he is over-come and tamed by Valentine, whose servant and comrade he becomes. The two eventually rescue their mother from the power of a giant. This is probably an ancient folktale later reinterpreted as a tale of romance.

Woodcut from The History of Valentine and Orson, 1800-1899, Chapbooks

Chapbooks v.33(22), Chapbooks, Newcastle University Special Collections, GB 186

This chapbook was printed in Newcastle by Margaret Angus and son, heirs of George Angus. The Anguses were a family of printers very active in the provincial trade of chapbooks. Moreover, George Angus is known for his collaboration with Thomas Bewick, the local woodblock engraver that popularised new engraving techniques aiming at integrating easily (and cheaply) illustrations in letterpress. Bewick’s illustrations of animals are striking for their modernity and inspired generations of illustrators of children’s books.

In the early nineteenth century, when this book was printed, children’s books were already recognised as an important segment of the book trade. This chapbook is not addressed to children explicitly, however it contains a hint: the verses after the title end with the prospect that the story would “instruct and delight” the reader. “Instruction and delight” was an expression appealing to parents and teachers, hence often used in educational books of the time. Moreover, at the bottom of the title page, the printer advertises other forms of cheap books that were intended as suitable for children and printed in high numbers.

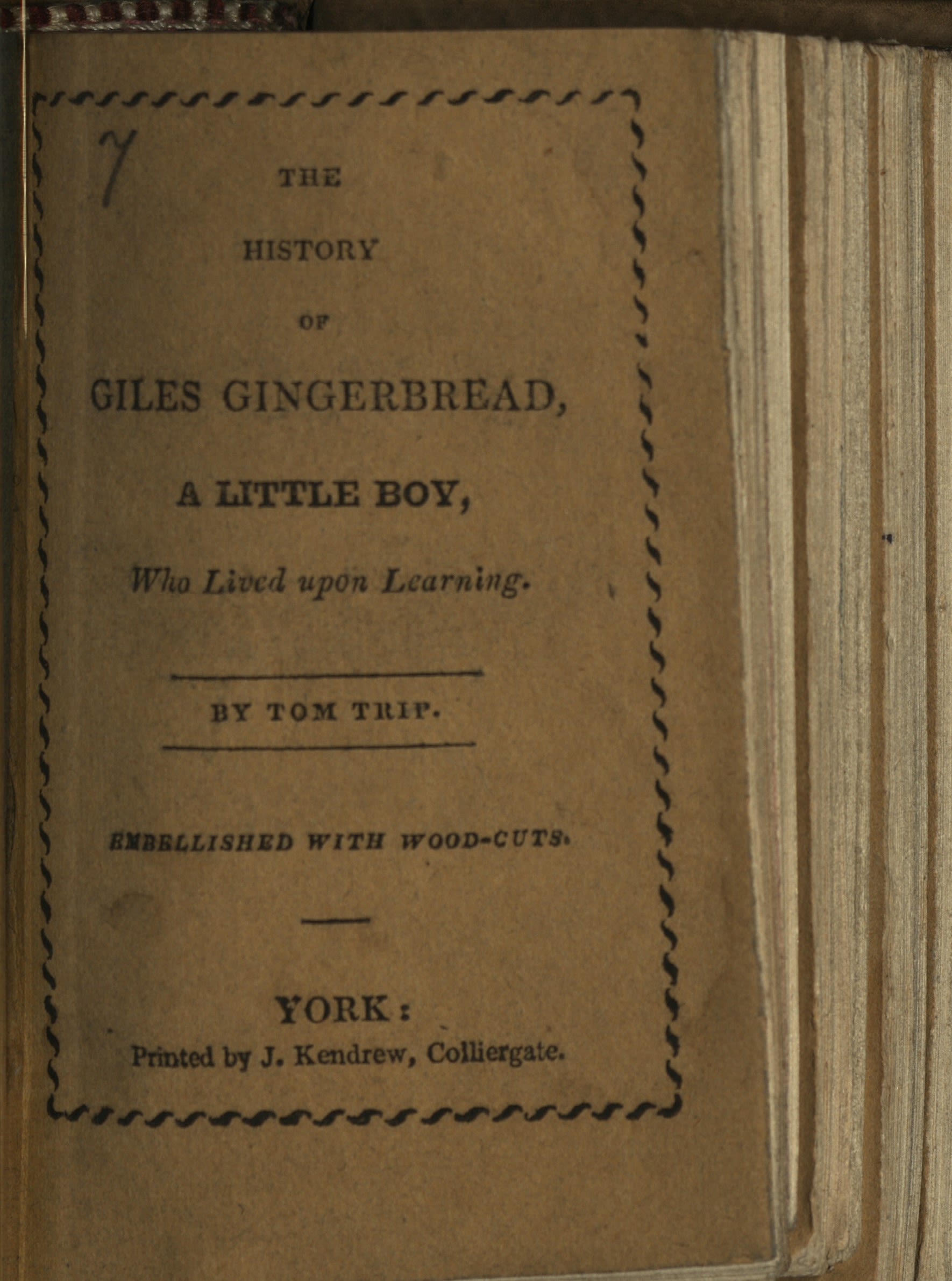

The History of Giles Gingerbread

The History of Giles gingerbread, a little boy, Who lived upon Learning, 1800-1899,

Chapbooks 398.87 KEN(7), Chapbooks, Newcastle University Special Collections, GB 186

Giles Gingerbread is a boy who learns his lessons by eating his way through gingerbread books made by his father. This book is very different from the other examples shown in this exhibition: it contains a didactic fiction specially written for children. It can be defined as a “children’s chapbook” and was printed by James Kendrew of York, one of the publishers that, in the first decades of the nineteenth century, deliberately adapted the chapbook format and contents to juvenile audiences.

Children’s chapbooks were often slightly smaller than standard chapbooks, and contained more illustrations, usually one on each page. Sometimes these were coloured by hand by unskilled workers or through stencils. Differently from standard chapbooks, they had simple covers (usually “sugar paper” in a choice of colours) that gave a different level of refinement to the booklets, although they remained cheap. The main difference with traditional chapbooks was that the texts were now adapted in a way that was intended to be suitable for children, both when they contained tales and stories from the past, expunged of any violent element or sexual reference, and when they proposed alphabets, nursery rhymes, or new didactic fictions, as in this example.

Differently from other examples shown here, that addressed children less explicitly and were usually printed by the traditional purveyors of cheap print, children chapbooks were something new, that related to the emergence of a new kind of children's literature, in Britain, from the 1740s. This was a phenomenon due to many societal and economic factors, and driven by entrepreneurial publishers, that first offered books to the children of affluent families but soon understood how to segment the market, giving life to children’s chapbooks. The latter did not supersede older chapbooks, they rather gave new life to a classic of popular print.

Find out more:

This virtual exhibition was brought to you by Newcastle University Library Special Collections & Archives and is part of CaTPoP, Children and Transnational Popular Print, 1700-1900: a research project based at the School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics, and funded by the European Union - H2020 Research & Innovation Programme, grant agreement 838161.

To find out more about CaTPoP, Children and Transnational Popular Print please visit @CaTPop20 on Twitter.

To find out more about Newcastle University Library Special Collections & Archives holdings please Browse our Collections.

To discover how you can consult materials please see Using our Collections.