People from the Pages

Discovering the stories of the people of 19th century India

This digital exhibition has been compiled by volunteer Charlotte Hawley and was inspired by research conducted in the Trevelyan (Charles Edward) Archive, held at Newcastle University Special Collections and Archives.

Note: As historical resources, some of the documents featured here reflect the racial prejudices of the era in which they were created, and some items include language or images which are offensive, oppressive and may cause upset. The use of such language and images is not condoned by Newcastle University, but we are committed to providing access to this material as evidence of the inequalities and attitudes of the time period.

Introduction: India after 1857

The years that followed the First War of Independence for India in 1857 were incredibly turbulent. The East India Company was dismantled and the British Government took over the running of the country.

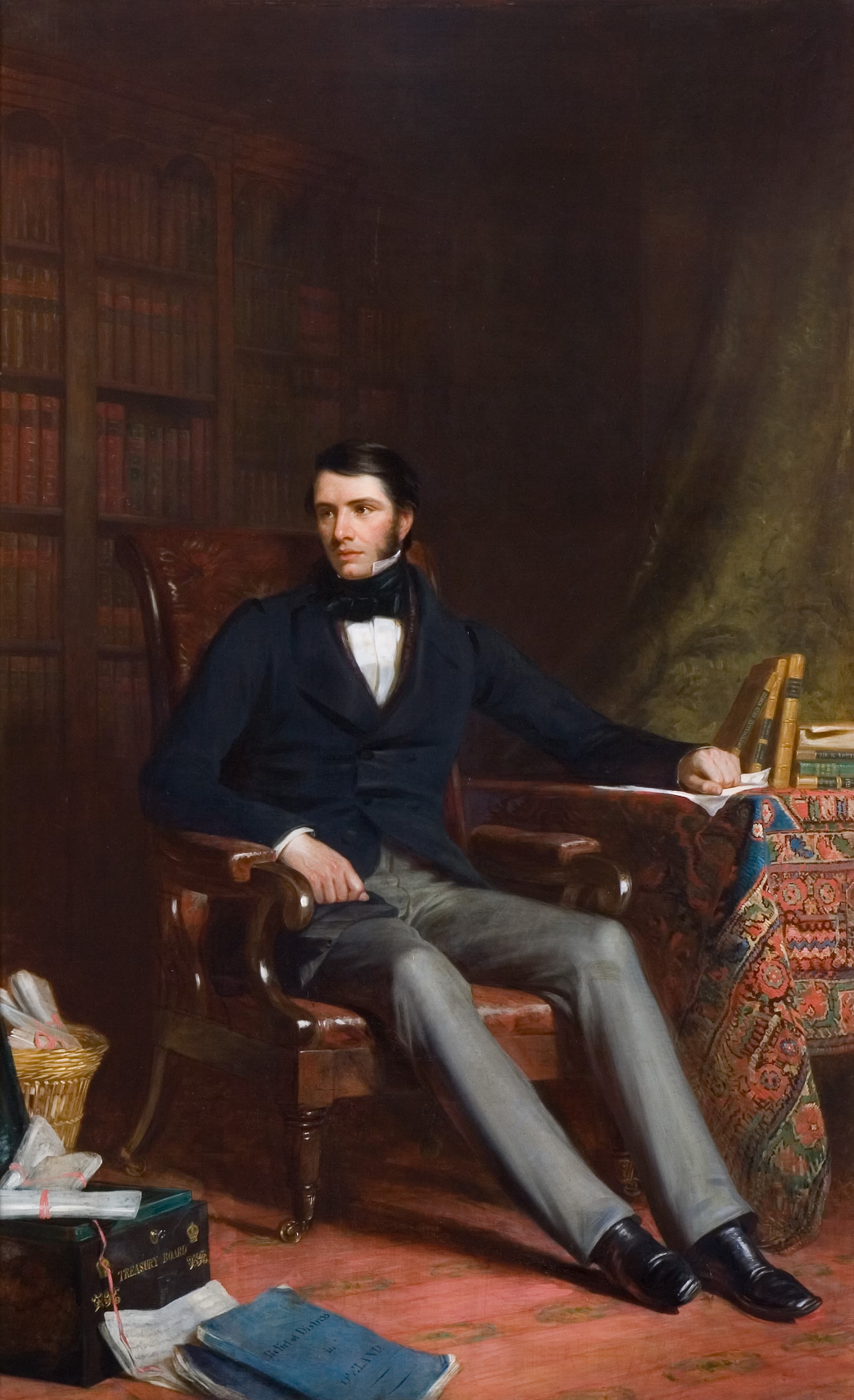

In 1958 Sir Charles Edward Trevelyan was appointed Governor of Madras. This followed 20 years at HM Treasury, for which he became best known due to his involvement in the inadequate administration of relief during the Great Famine in Ireland.

Sir Charles was a prolific writer during his career as a colonial administrator in both India and Ireland. His archive is kept in the Special Collections & Archives at Newcastle University, and comprise of correspondence spanning over 60 years. The letters and collected newspaper clippings within the archive provide a snapshot of life in 19th century, particularly Chennai (formally Madras).

This digital exhibition uses items from Sir Charles’ archive to identify and illuminate some of the people and social groups in 1850s Chennai whose narratives have traditionally been overlooked, and considers the impact of the British Colonial Administration on their lives. It will also explore how Sir Charles, as a newly appointed Governor perceived the local communities, both in the public eye and in his private life.

Sir Charles Edward Trevelyan, by Eden Upton Eddis, (National Trust NT584410)

Sir Charles Edward Trevelyan, National Trust. NT584410

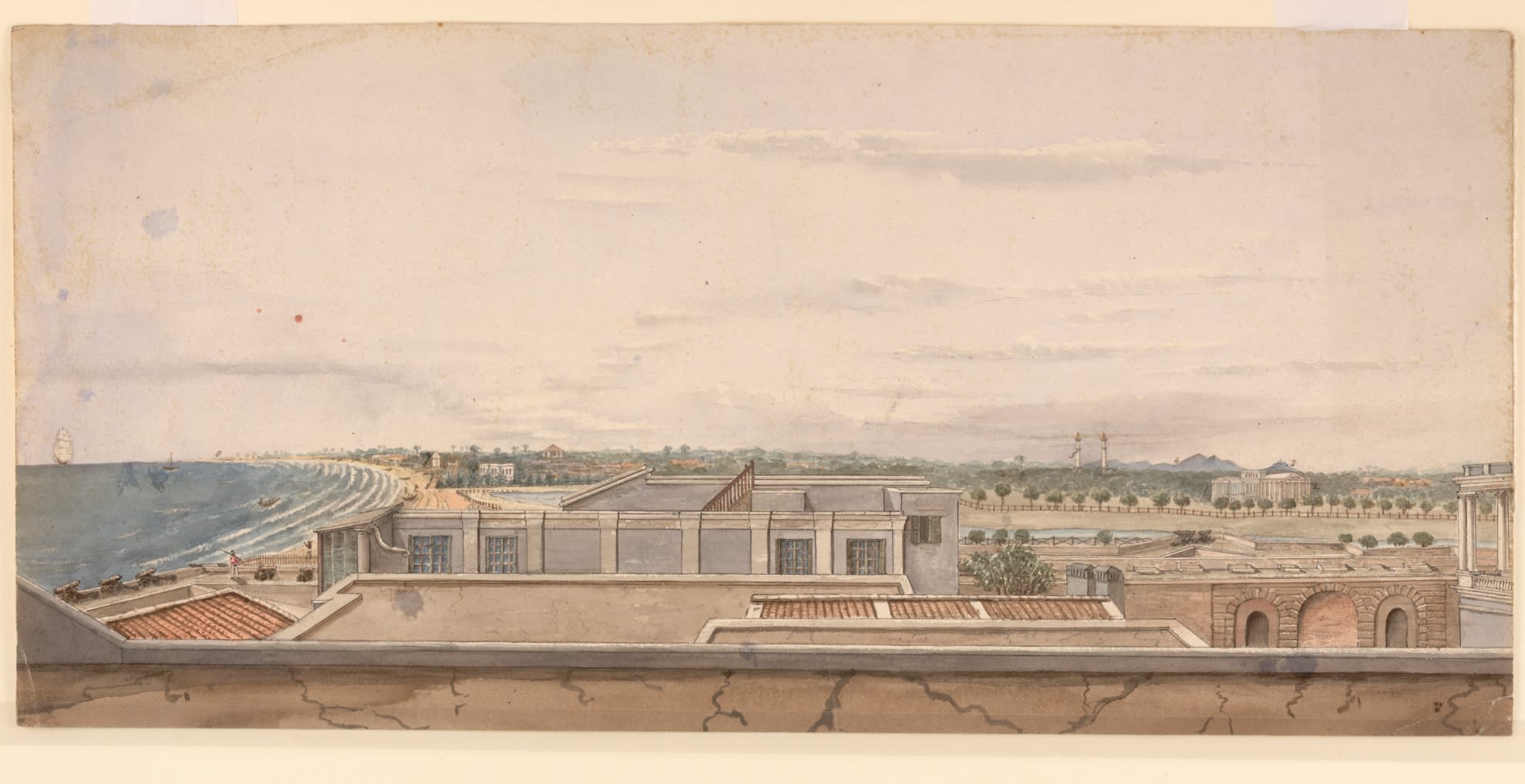

'Thank God all prosperous with me. When I went over the side of the Nubia alone I felt that I was taking the plunge - but I was kindly received by the Chief authorities and a great crowd of People on the Beach, where I got into Lord Harris' carriage and was driven to the Council Rooms to be sworn in'

Sir Charles Trevelyan in a letter to his wife, Hannah. April 1859 (CET/10/11/13)

No permanent harbour was built at Chennai until the late 19th century. Prior to that the ships dropped anchor a distance from the shore and people, as well as goods, were rowed through the fierce surf in masula boats.

To view more digitised images from the Trevelyan (Sir Charles Edward) Archive visit CollectionsCaptured

Azim Jah (1802-74)

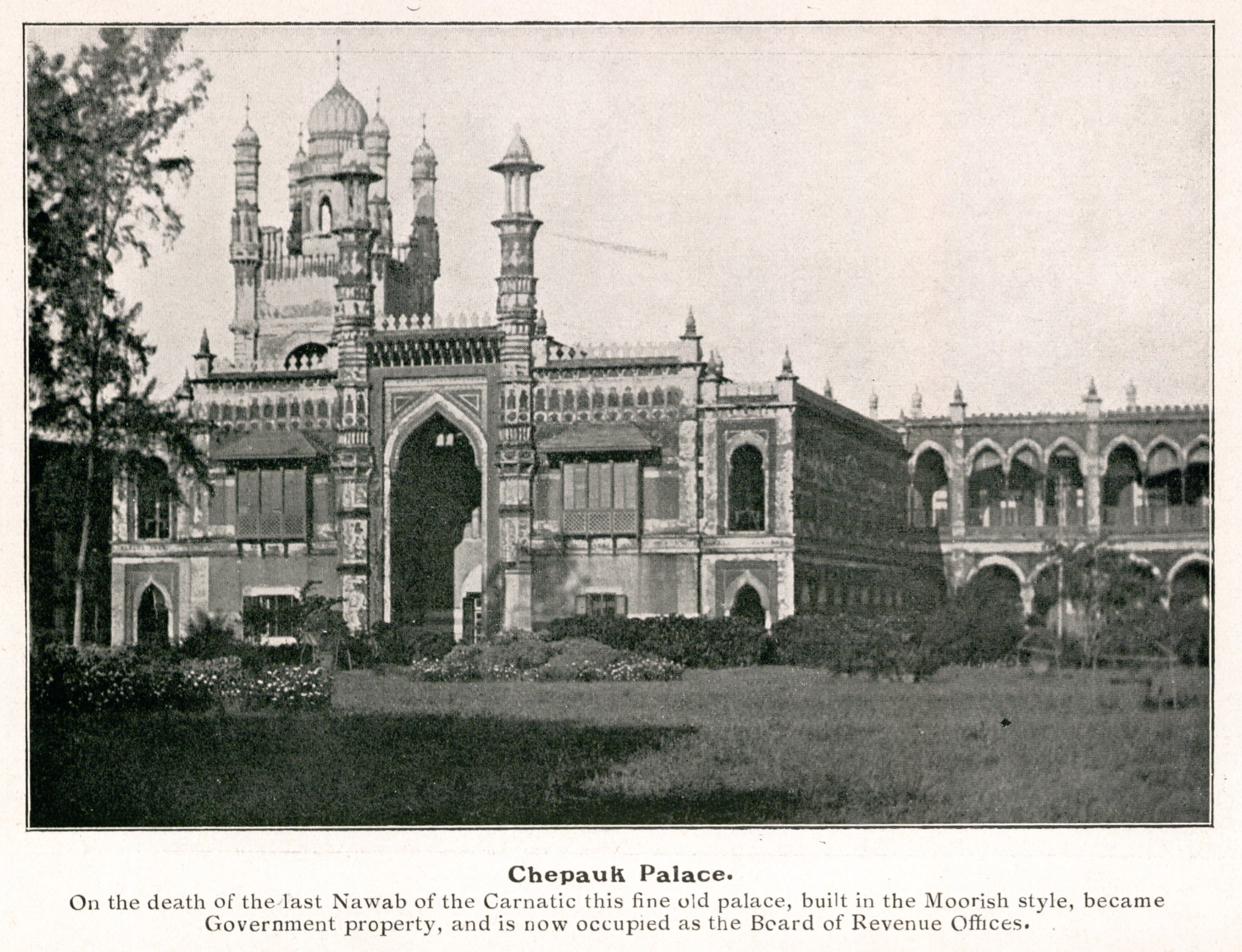

Amongst the 'Great crowd' that had arrived to welcome the new Governor was Azim Jah. He was the younger brother of the 11th Nawab of the Carnatic and uncle to the 12th and last Nawab Ghulum Muhammed Ghouse Khan.

Prince Azeem Jah drove in at this time in a carriage and four with Sepoy outriders before, and some Nabob beside him and a long train of native gentlemen behind him

In 1855, the last Nawab of the Carnatic died without an heir. The British annexed his lands by applying the Doctrine of Lapse. Azim Jah protested claiming that he was the legitimate successor to the throne, but this proved unsuccessful.

Chepauk Palace, c.1905, from India Illustrated (Special Collections, University of Houston Libraries, DS413 .I6x, Page 57).

Chepauk Palace, c.1905, from India Illustrated (Special Collections, University of Houston Libraries, DS413 .I6x, Page 57).

The Nawab's home, the Chepauk Palace was sold off and eventually purchased by the Madras government. They were later offered the Amir Mahal palace where the descendants still live today in Chennai.

We are a fallen people; we were once the rulers of this land, but for many years we have been subjected to indifference and neglect; under your rule, however, our hopes revived, not, it is true, of reobtaining our ancient possession, but of rising in the scale of social civilisation.

In 1867, Azim Jah was granted the title of Nawab of Arcot or Amir-i-Arcot by Queen Victoria and given a pension.

Azim Jah (Alamy, Image ID PJ41YD)

Azim Jah (Alamy, Image ID PJ41YD)

Colonel James Skinner (1778 – 1841)

Portrait of Colonel James Skinner in uniform, (c.1830) from Skinner's own Tazkirat al-Umara, or Account of the Nobles [of Delhi and its neighbourhood] (© British Library B20037-51)

Portrait of Colonel James Skinner in uniform, (c.1830) from Skinner's own Tazkirat al-Umara, or Account of the Nobles [of Delhi and its neighbourhood] (© British Library B20037-51)

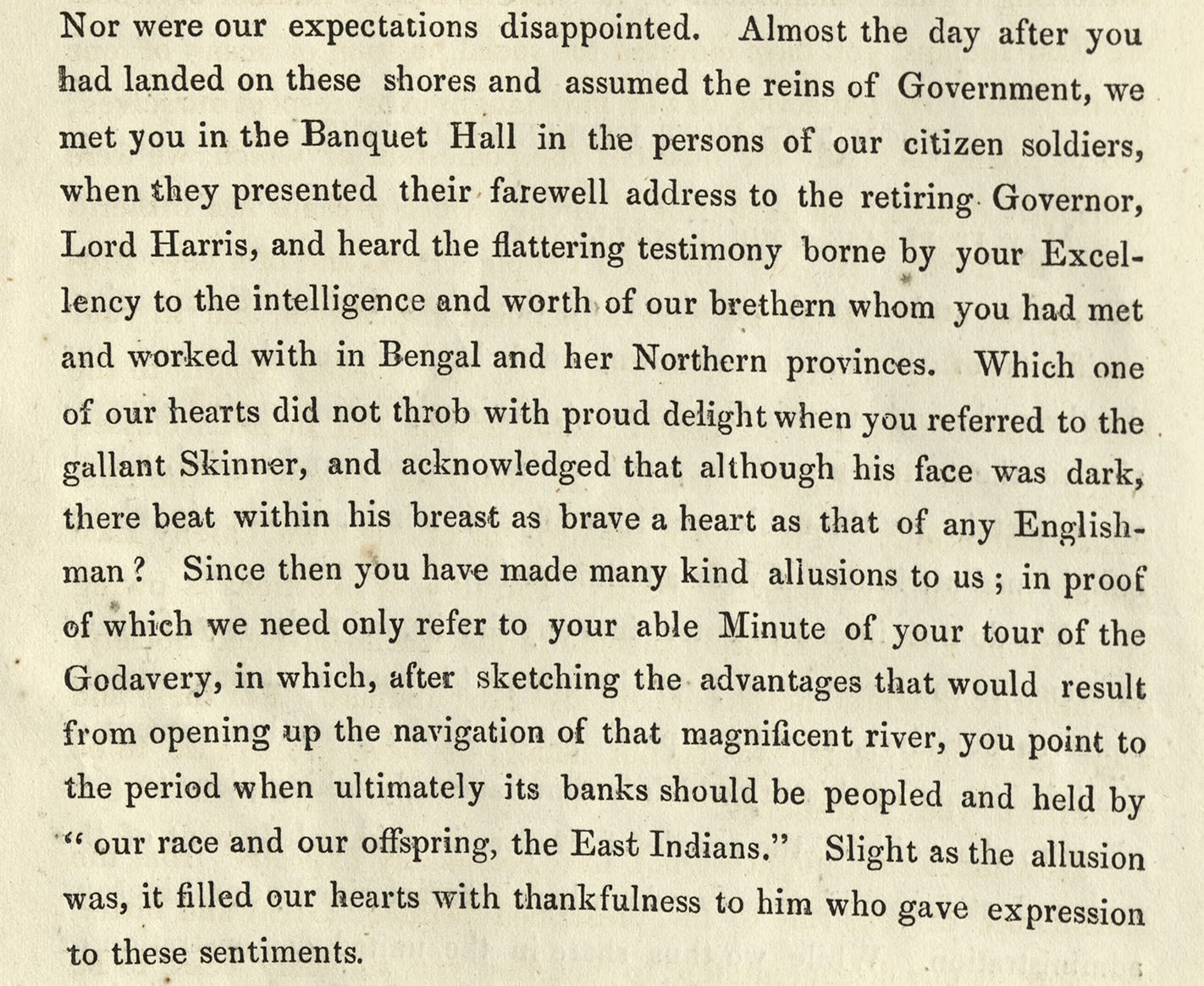

Trevelyan first became aware of Colonel Skinner when he worked for the East India Company in Calcutta in the 1820's. He was quite a celebrity in India and Trevelyan used his popularity in one of his first speeches in Madras to make a positive connection with the Anglo-Indian community.

"Almost the day after you had landed on these shores and assumed the reins of Government, we met you in the Banquet Hall...and heard flattering testimony borne by your Excellency to the intelligence and worth of our brethren whom you had met and worked with in Bengal and her Northern provinces. Which one of our hearts did not throb with proud delight when you referred to the gallant Skinner, and acknowledged that although his face was dark. There beat within his breast as brave a heart as that of any Englishman?"

Colonel Skinner was the son of a Scottish Mercenary called Hercules Skinner and his mother was the daughter of a Rajput Zamindar (land holder or local ruler). He was one of seven children and was educated at the English School in Kolkata (formerly Calcutta).

After running away from home, Skinner joined the Maratha army. He was later ejected from the Marathas due to his British father after the outbreak of the 2nd Anglo-Maratha War in 1803. James ended up fighting for the East India Company, where he experienced discrimination due to his mixed heritage.

He famously raised two cavalry units for the British, later known as 1st and 2nd Skinner's Horse and nicknamed 'The Yellow Boys' for their flamboyant yellow uniforms. The units still exist in the Indian army today.

Skinner was a Christian and was responsible for building St. James', the first church in Delhi. He also built a Hindu temple and a mosque.

He lived exclusively a Mughal lifestyle with a Mughal title, often shortened to 'Sikandar Sahib' and he had many wives and bibis. One English visitor on meeting him remarked 'there are any number of beautiful Mrs Skinners' (Dalrymple, The Last Mughal).

Corruption and 'Jobbery'

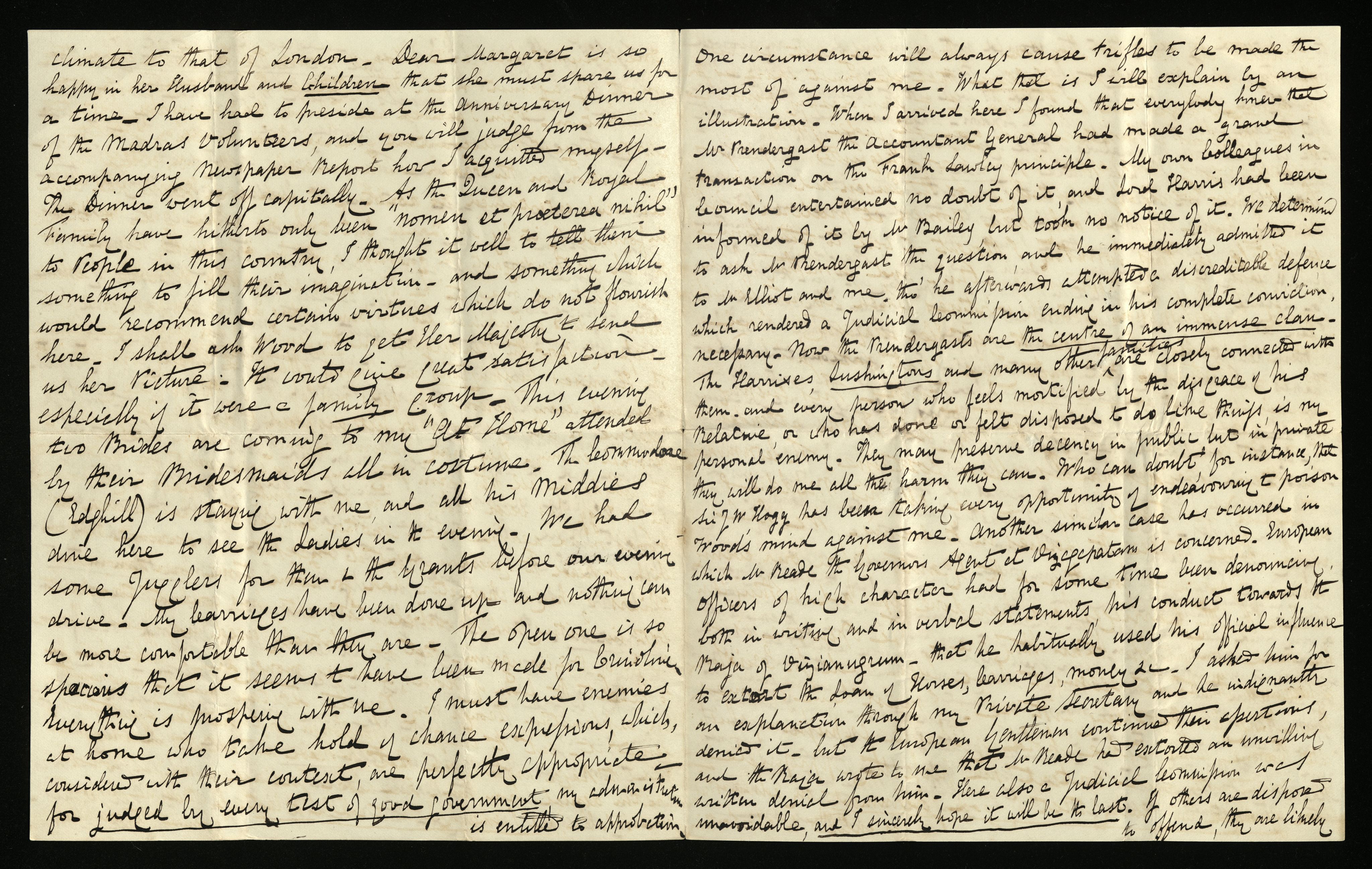

Not long after his arrival in Madras, Sir Charles quickly became aware of the corruption within the Madras Presidency. In his letters home, he writes about his dislike for 'jobbery', the practice of using a public office for one's own gain. He highlights two particular cases of corruption and his desire to tackle this problem that seemed endemic in British India.

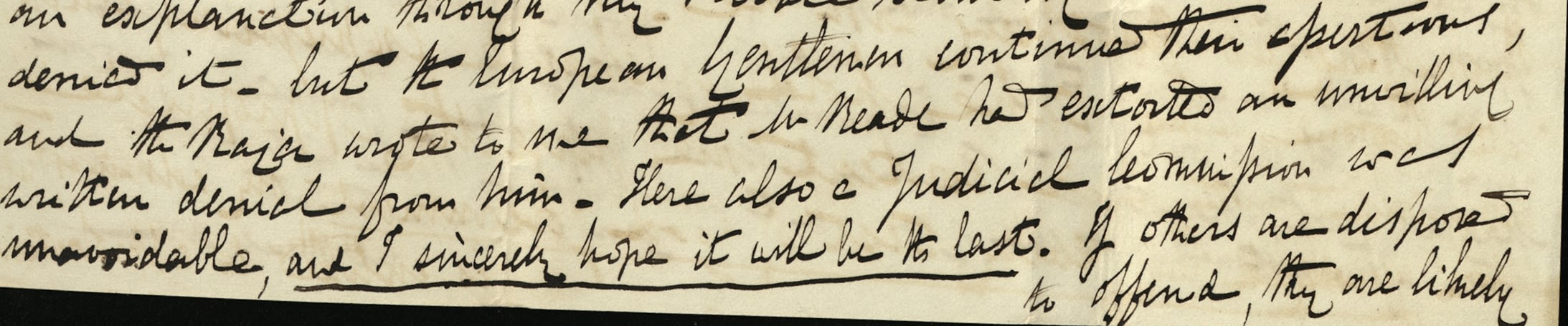

Trevelyan writes about the case of Charles Reade, the Governor's agent in Visakhapatnam (formerly Vizagapatam).

"European officers of high character have for some time been denouncing both in writing and in verbal statements his conduct towards the Raja of Vizianagrum (sic)".

The Governor's agent was accused of borrowing two horses and two elephants from Pusapati Vijayarama Gajapathi Raju III (1826-79), Rajah of Vizianagaram. He later also borrowed two mirrors from the Rajah to fit up his own Drawing Room for a visit from Lord Harris, then Governor of Madras. None of the items were returned to the Rajah. They were later paid for with cheques, but these were discovered to have been backdated after the accusations of corruption had come to light. Reade was also accused of pressurising the Rajah to write letters of support for him.

"[Reade] violated repeated orders of the Government and the ordinary instincts of an English gentleman in order to have the use of two horses, two elephants, and two mirrors without paying for their keep; that when he was found out he coerced a intimate friend into telling a lie to conceal the transaction"

Reade, a government official of 22 years decided to retire before facing an official investigation, but the case was reported widely in newspapers in India and Britain.

Pusapati Vijayarama Gajapathi Raju III ascended to the throne in 1845 and reigned until his death in 1879.

Another corruption case mentioned by Trevelyan in his letters involved the Accountant General, Mr Guy Lushington Prendergast. An anonymous testimony was sent to Trevelyan, which accused Prendergast of using his position to gain insider knowledge of the 'Tanjore Debt' and using it for financial gain. It had secretly been announced that the debt was to be paid off by the government.

Only three days after he had received the official communication, a well known Soucar (Hindu Banker), Lutchmedut Davey arrived at Prendergast's office and through Prendergast's subordinates purchased 30,000 rupees of Tanjore bonds. He purchased more bonds on another two occasions. When the news of the debt was to be paid off, the bonds value greatly increased and made the Accountant General a profit.

At first Prendergast freely admitted his actions to the Governor and Mr Elliot. Later, when faced with a judicial commission called by Trevelyan, he changed his mind and denied the accusations laid against him. He was found guilty and sent home in disgrace.

"Here also a judicial commission was unavoidable and I hope the last. If others are disposed to offend, they are likely to be deterred by seeing that they would not be indulged with an avowed impunity"

Builders of Chennai

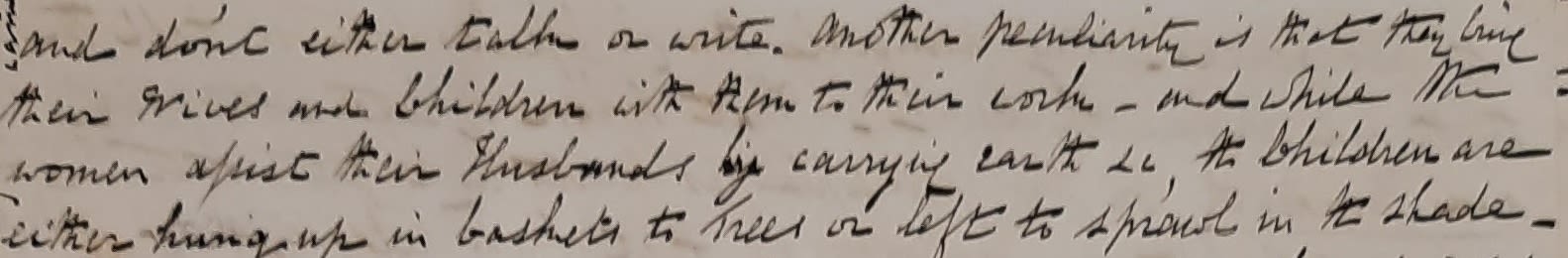

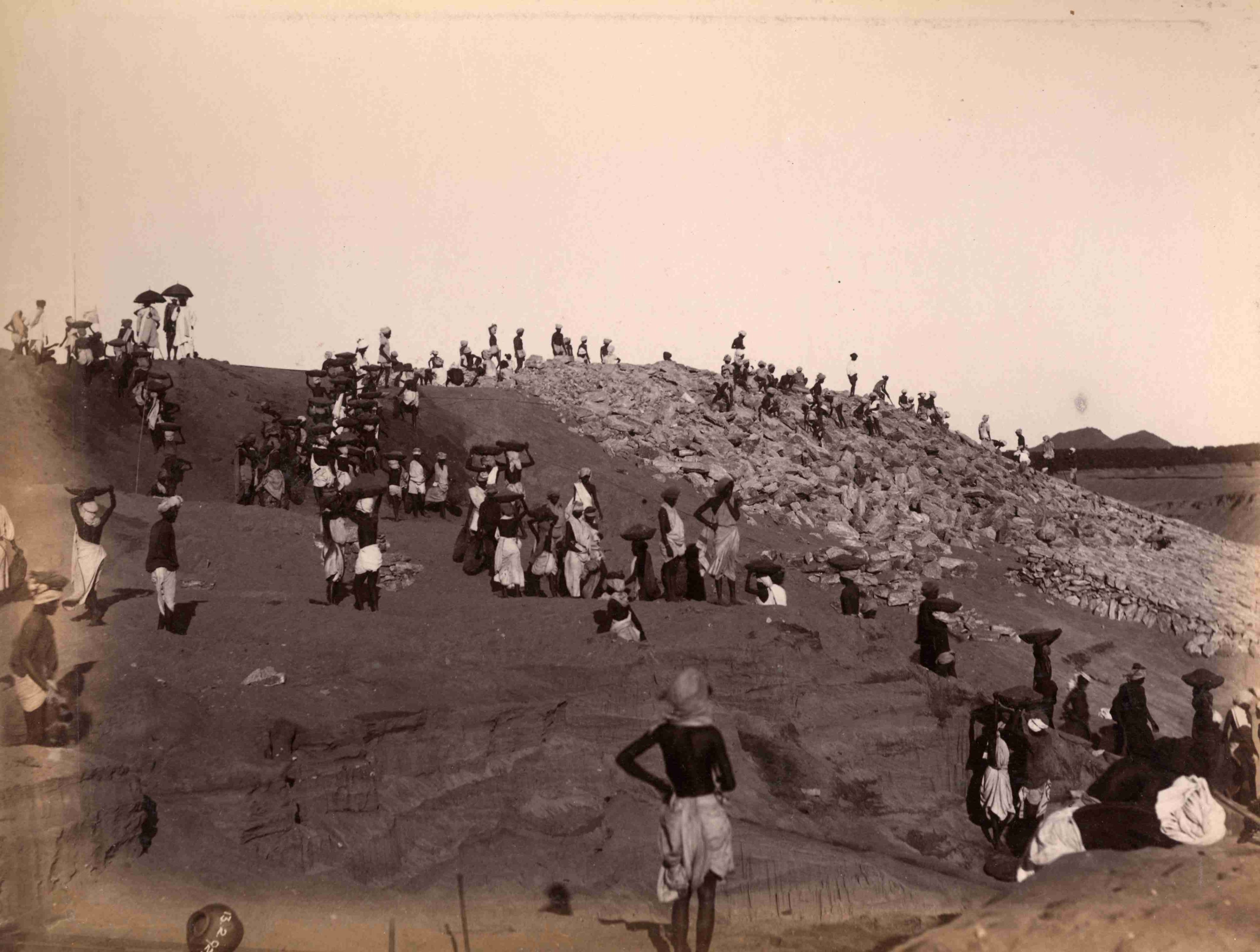

In letters to his wife Harriet, Charles excitedly explains his plans for improvement in Chennai. In one of his letters he vividly describes the 'Wuddas or Indian Navvies' to her.

They only work and don't either talk or write. Another peculiarity is that they bring their wives and children with them to their work and while the women assist their husbands by carrying earth etc., the children are either hung up in baskets to trees or left to sprawl in the shade'

This group was present in the early history of India and continuously thereafter. These circulating labourers were critical to any construction in India and were employed by the Mughals and Tipu Sultan to work on their forts, reservoirs and temples. The British knew them as 'Wudder' or 'Wuddas' but their name depended on what area of India they worked in.

The workers Trevelyan describes in his letter most likely came from the Telegu speaking parts of the Deccan south. Nomadic groups, like the Wudder/Wuddas, were employed alongside general labourers at large construction sites to act as 'pacesetters' for others working at the site. They were highly prized for their work in stone and earth and for their skills and efficiency.

Francis Buchanan travelled around the South of India and published a book in 1807 about his journey. His description showed this community to be more than implied by Trevelyan's narrow and almost judgemental label 'Indian Navvies'.

" They dig canals, wells and tanks, build dams and reservoirs, make roads, and trade in salt, and grain. Some were farmers, but they never hire themselves out as Batiguru, or servants employed in agriculture...There are no distinctions among them that prevent intermarriages, or eating in common"

This fluid community was increasingly stigmatised by the British as the 19th Century went on. By the time Edward Thurston published his 1909 book 'Castes and Tribes of Southern India' he divided the 'Wudders' into 23 categories. They were often treated with suspicion and considered a threat to social stability due to their nomadic lifestyle and being outside of the traditional caste system.

Background image: Kistna Bridge, Bezwada 12 spans of 30 Feet, by F.J.E. Spring (courtesy of the Library of the Institution of Civil Engineers, London).

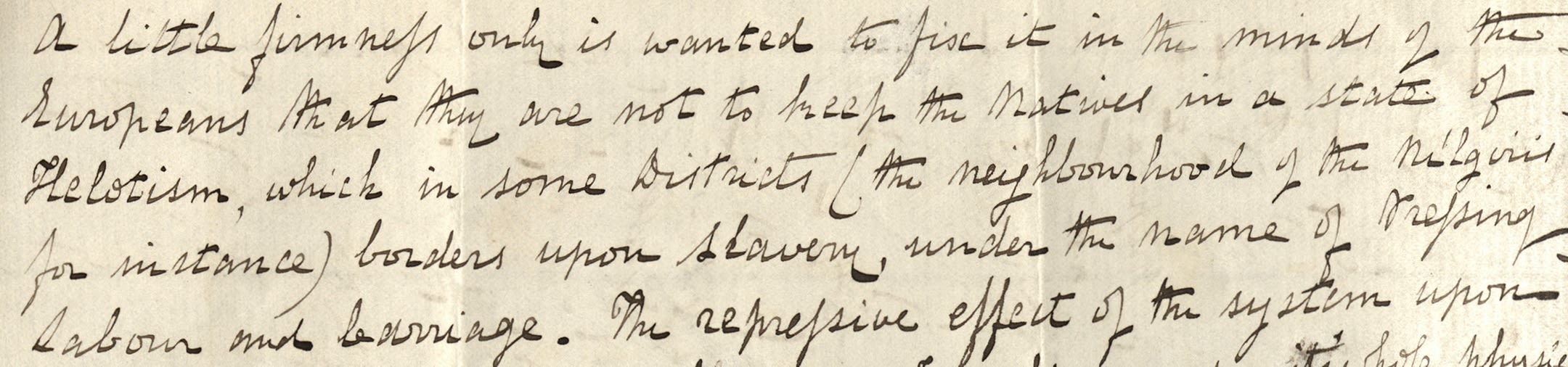

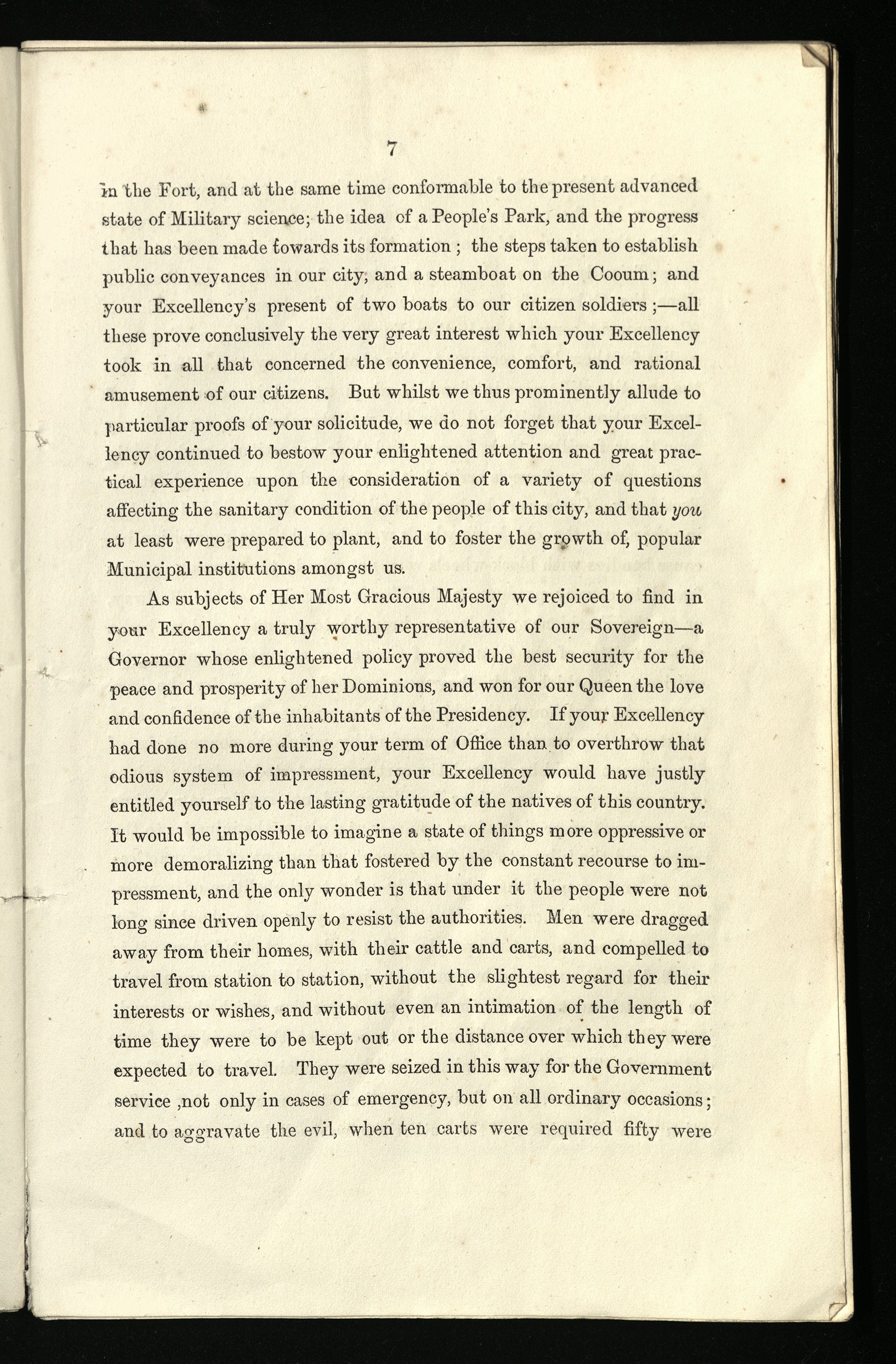

One terrible practice affecting workers and highlighted in Sir Charles's letters was the system of impressment of carts and cattle, he called 'this monster evil', noting that it 'bordered upon slavery':

'A little firmness only is wanted to fix it in the minds of the Europeans that they are not to keep the Natives in a state of Helotism'

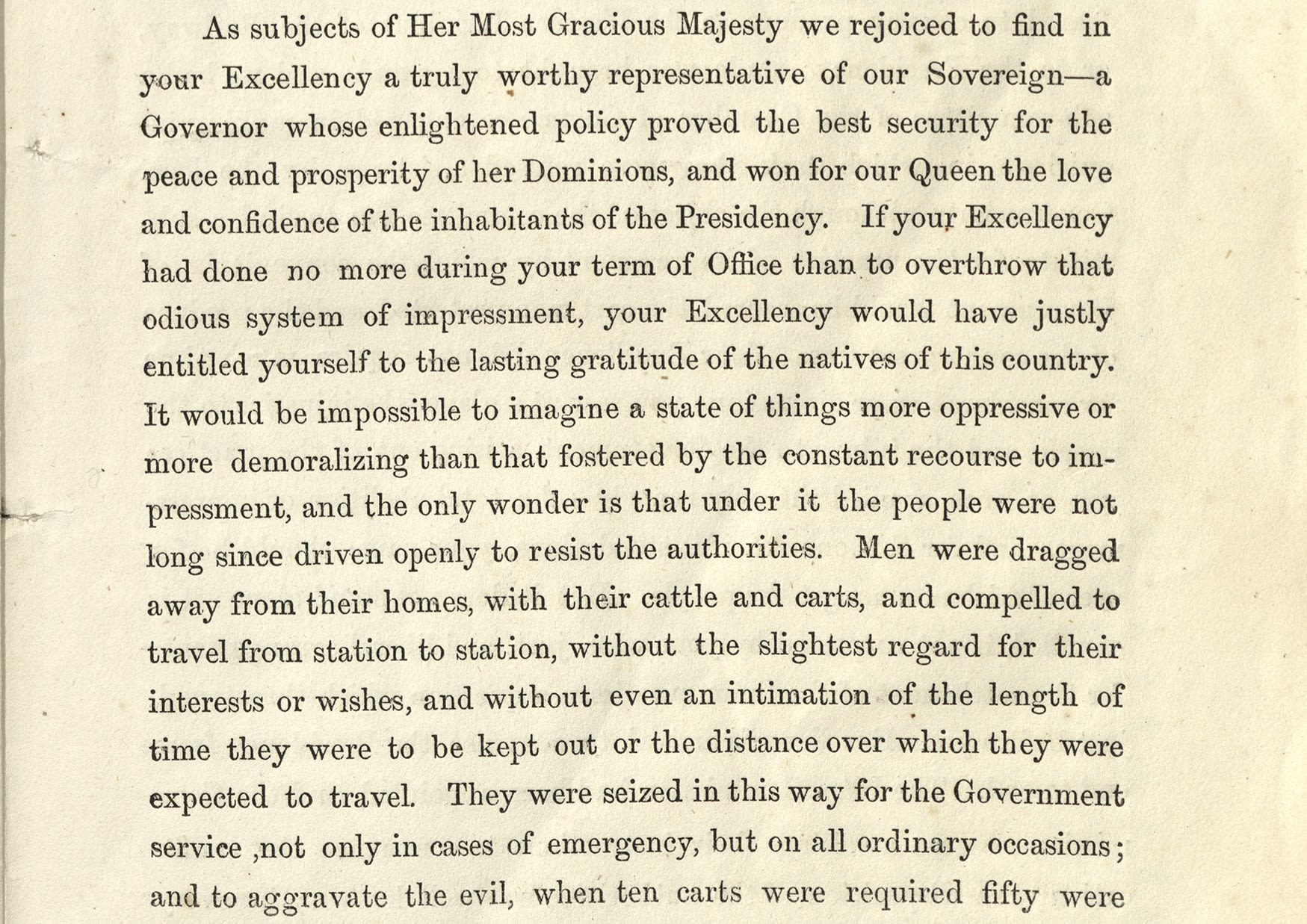

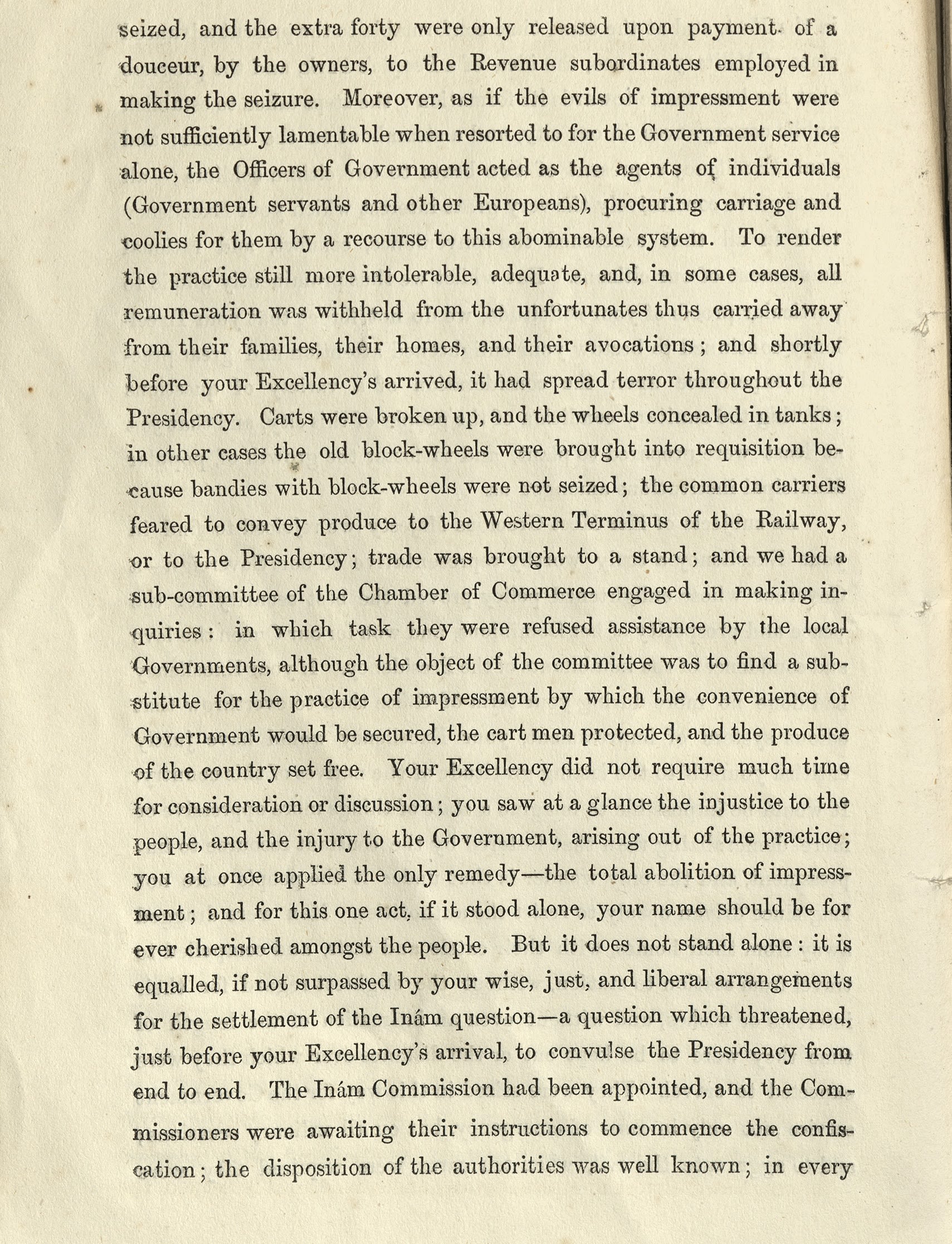

The barbaric practice was described by the Indian community in the following Address, given to Sir Charles on his departure from Chennai in June 1860.

Extracts from printed pamphlet (June 1860), from Address from the Mohemmedan Community of Madras to Sir Charles Edward Trevelyan (CET/2/42 pp.7-8)

Extracts from printed pamphlet (June 1860), from Address from the Mohemmedan Community of Madras to Sir Charles Edward Trevelyan (CET/2/42 pp.7-8)

The practice of impressment spread terror throughout the Presidency. People were taken against their will from their families, homes and jobs. It could be for any amount of time and there was no payment.

In a desperate bid to avoid it, Indian cart owners broke up their carts and wheels were hidden out of sight.

Sir Charles Trevelyan abolished the practice within the presidency soon after arriving as Governor of Madras.

Servants in the British Raj

Indian servants were an indispensable part of every day life for most British families. Often they were used in large numbers, with middling income families having 15 servants. Despite this, very few of their names are recorded. Sir Charles does not mention any of his Indian servants by name.

There were a number of servant roles in a household such as Sir Charles's in the 1860's.

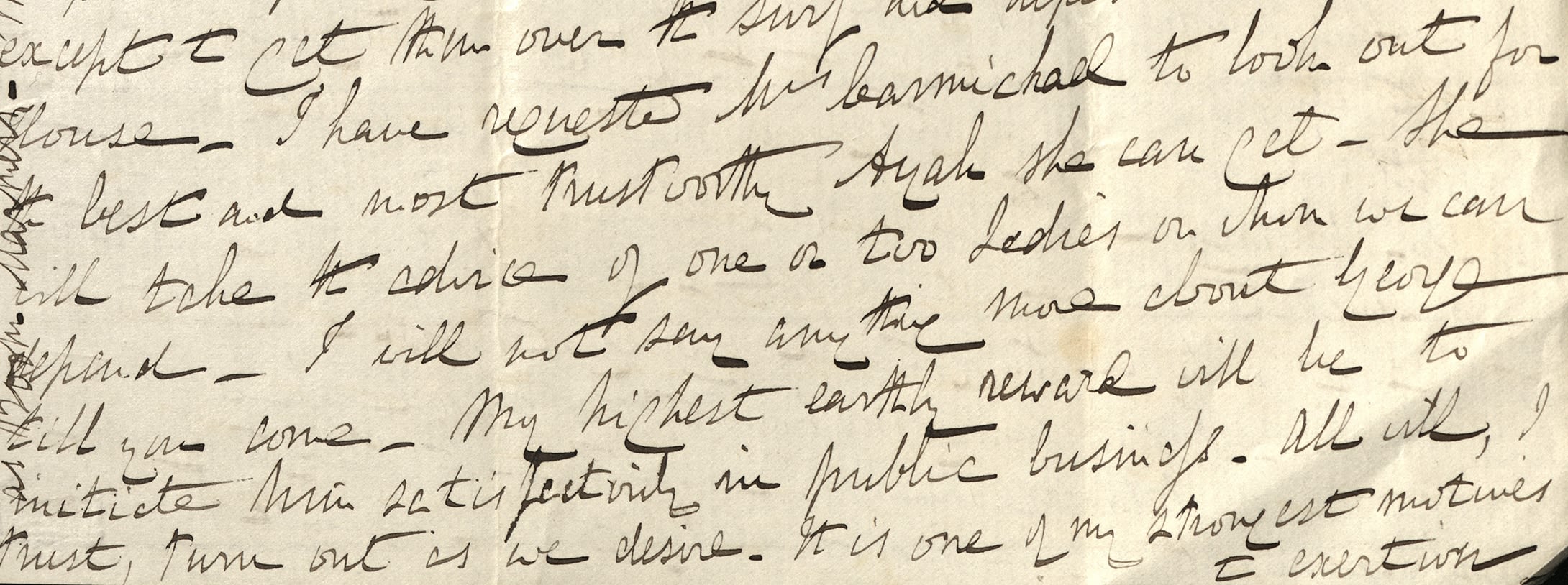

An Ayah was a lady who traditionally looked after the children. Interestingly, Sir Charles promised to find Hannah the best Ayah when she comes to join him in Madras. In this context he used the term to mean a ladies maid.

I have requested Mrs Carmichael to look out for the best and most trustworthy Ayah she can get.

In his letters he also mentioned that he employs servants called punkahwalas or punkamen who used punkahs or fans to keep him cool.

There were bhisties or water carriers to bring fresh water into the house and masalchis, whose responsibility it was to light lamps and candles.

Unlike at home in Britain, most servants in India were men. Many of those employed were landless labourers from the outlying areas of the Bengal, Madras and Bombay Presidencies.

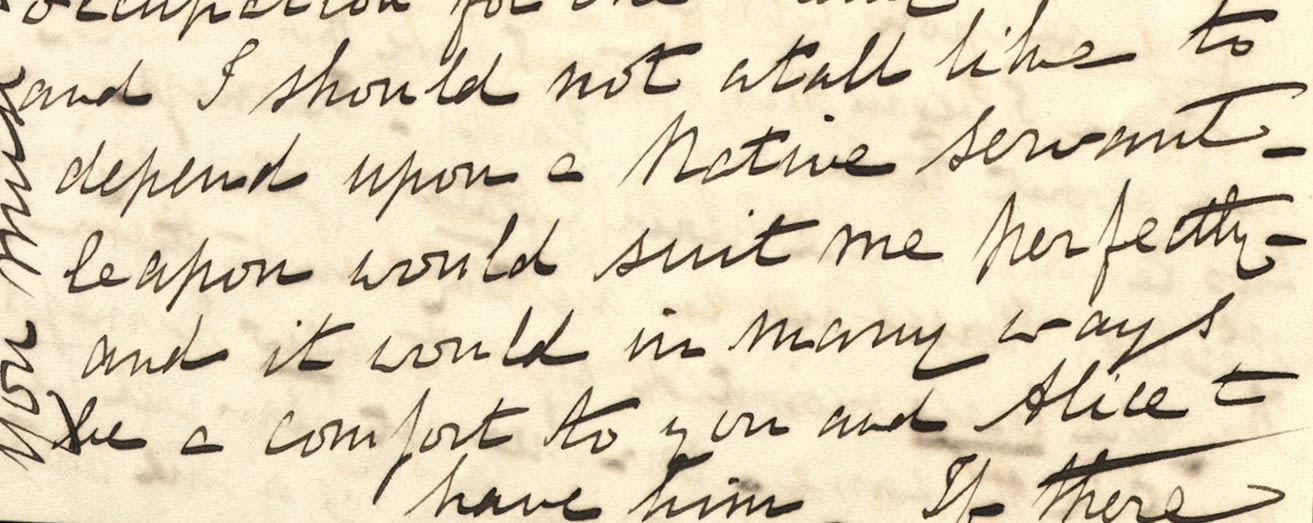

On the departure of his British servant, Mr Carmichael, Sir Charles refuses to employ an Indian valet. This highlights the prejudices many Indian servants faced from their British employers. Instead he instructs his wife to bring out his servant from England.

I should not like at all to depend upon a Native servant

Indian servants often faced racism and discrimination in British households. One advice manual for British women setting up a colonial household advised "Where it is possible to cheat, they [Indian servants] will generally do so".

Some of the advice manuals, many written by British woman, continually reiterated the physical, moral and intellectual inferiority of the Indian servant. These all contributed to the feelings of British supremacy and the legitimacy of Imperialism, particularly after the events of 1857.

Very few British people, particularly the women who might take responsibility for running the household, could speak or understand any Indian languages. This barrier contributed to much of the intolerance shown to servants and to the mistaken apprehension that Indian servants were slow or lacking in intelligence.

Domestic servants were often held in low esteem in Britain, but this perception was made worse in India because of the colour of their skin, religious differences, social, cultural and linguistic differences between the British and Indians.

Background image: Domestic Servants, Madras, 1870 (© British Library 1000/52 Item 4962)

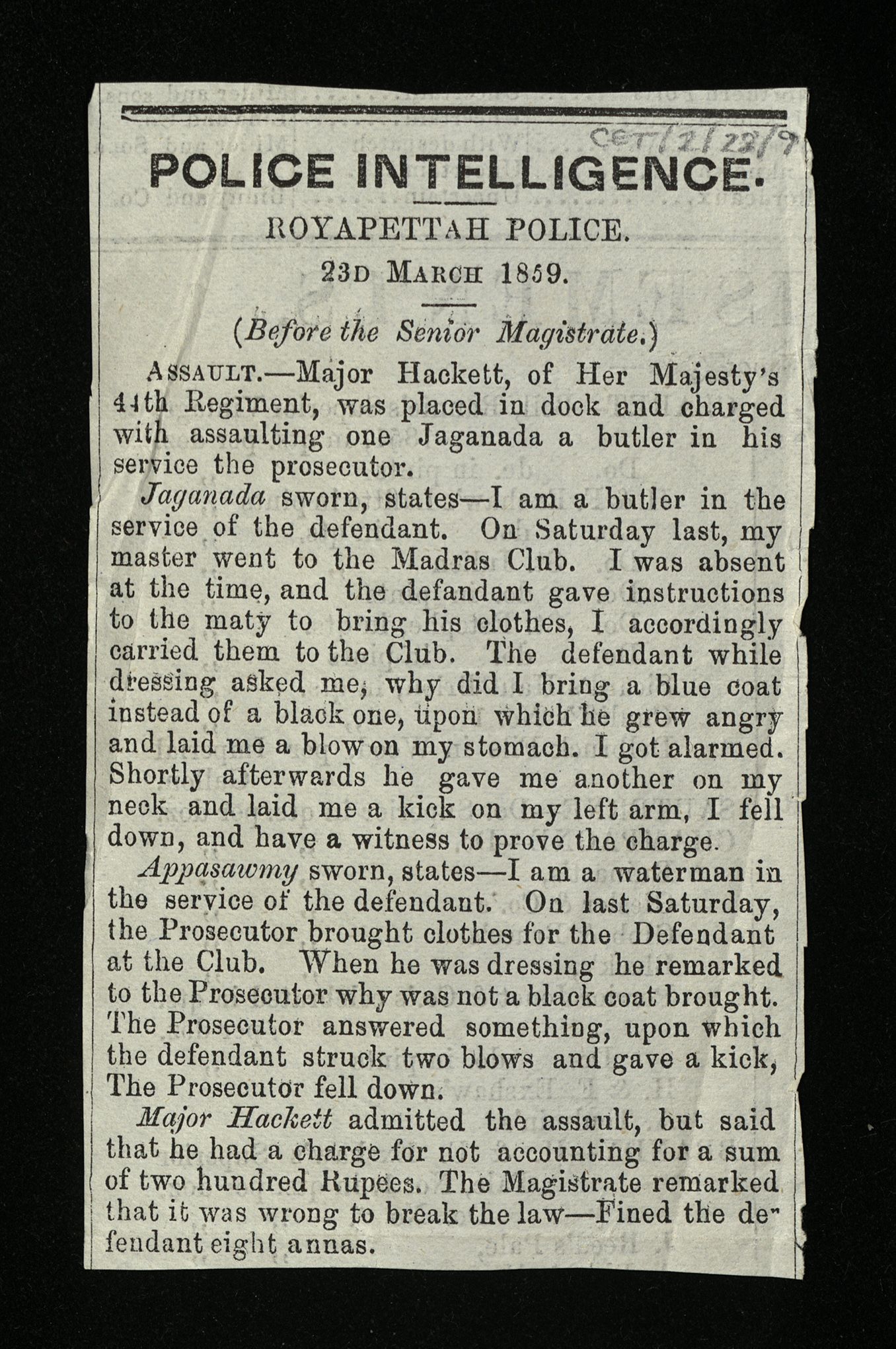

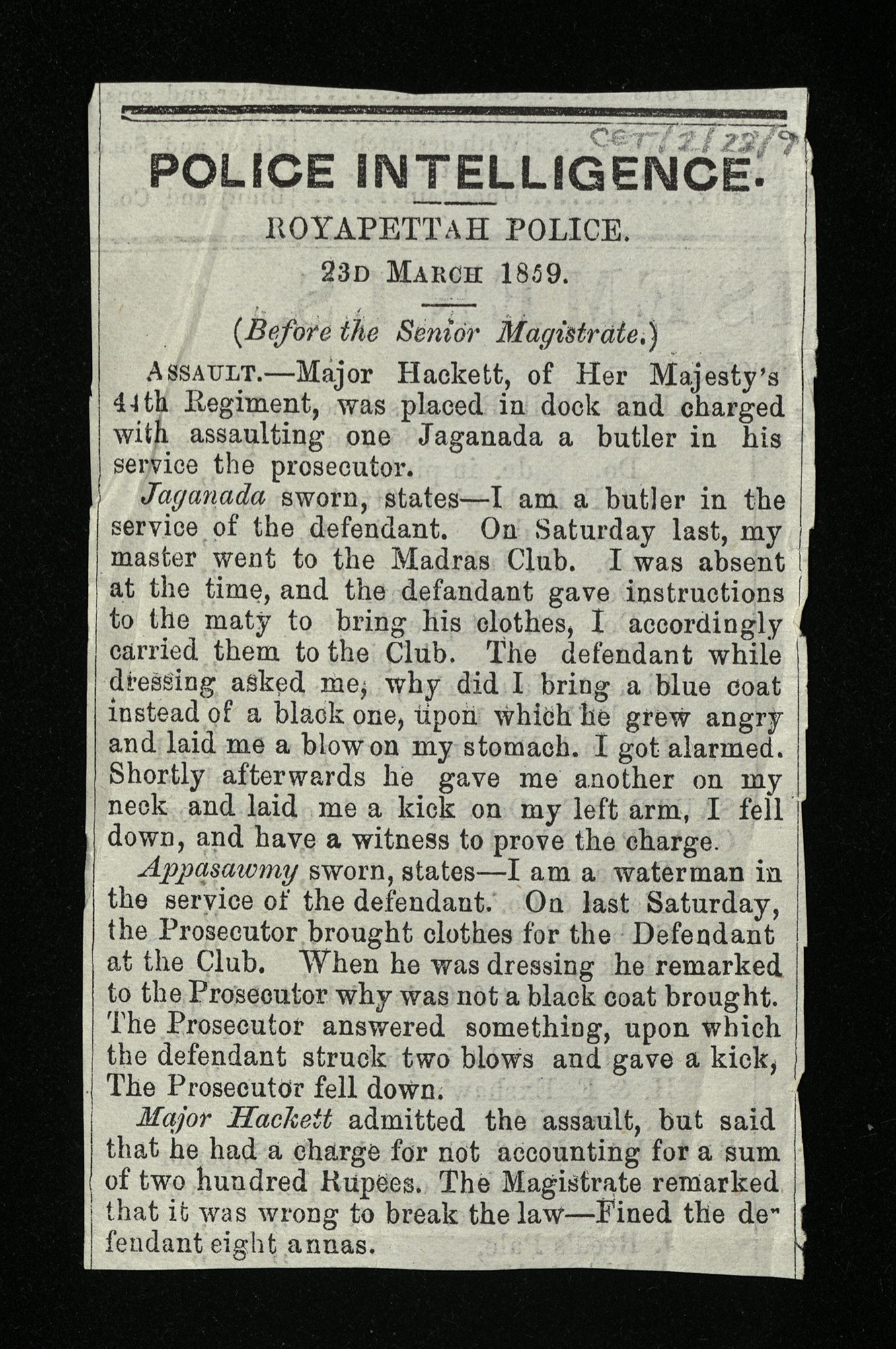

Unlike in Britain where beating a servant was rare, and outlawed in 1860, beatings of servants in India was common and widespread. There are endless examples; Mrs Mary Wimberley flogged her carriage driver, whilst Flora Annie Steel whipped her servant for mistreating her mule (Servants Past, 2015-18). The cases of abuse rarely ended up in court, and when they did the punishments were insignificant.

Amongst Sir Charles's papers was this newspaper cutting. It describes a case of a Major Hackett who assaulted his Indian servant, called Jagananda, and was fined eight annas (1/16 of a rupee).

Newspaper clipping from an unknown publication. (CET/2/28/9)

Newspaper clipping from an unknown publication. (CET/2/28/9)

Sadly, cases like this were extremely common in India.

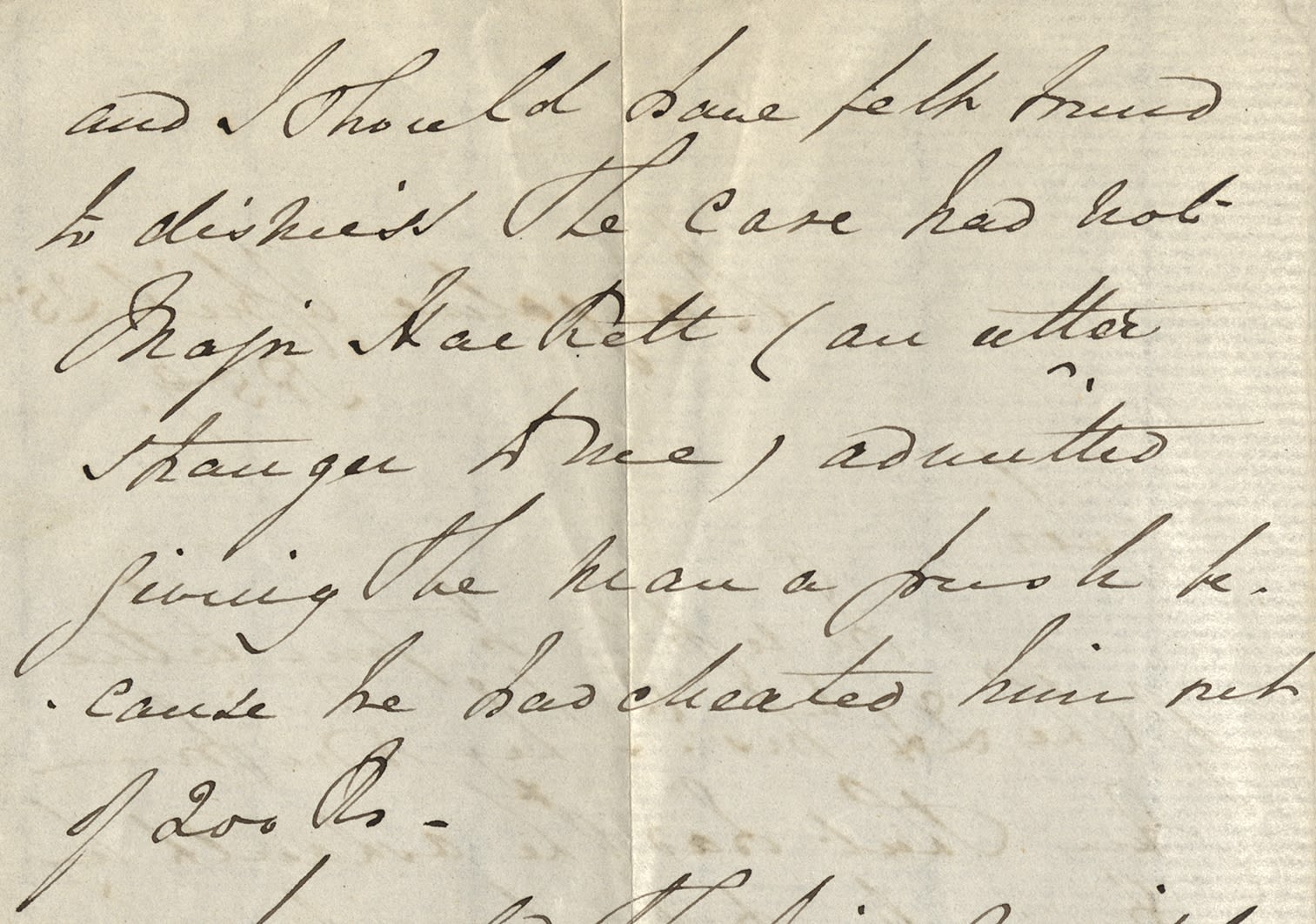

Amongst the documents in the archive also survives a letter from the Judge presiding over this case, justifying the leniency of the sentence. According to the Police Act the fine for such a crime should have been 100 annas.

"I should have felt bound to dismiss the case had not Major Hackett (an utter stranger to me) admitted giving the man a push because he had cheated him out of 200rps."

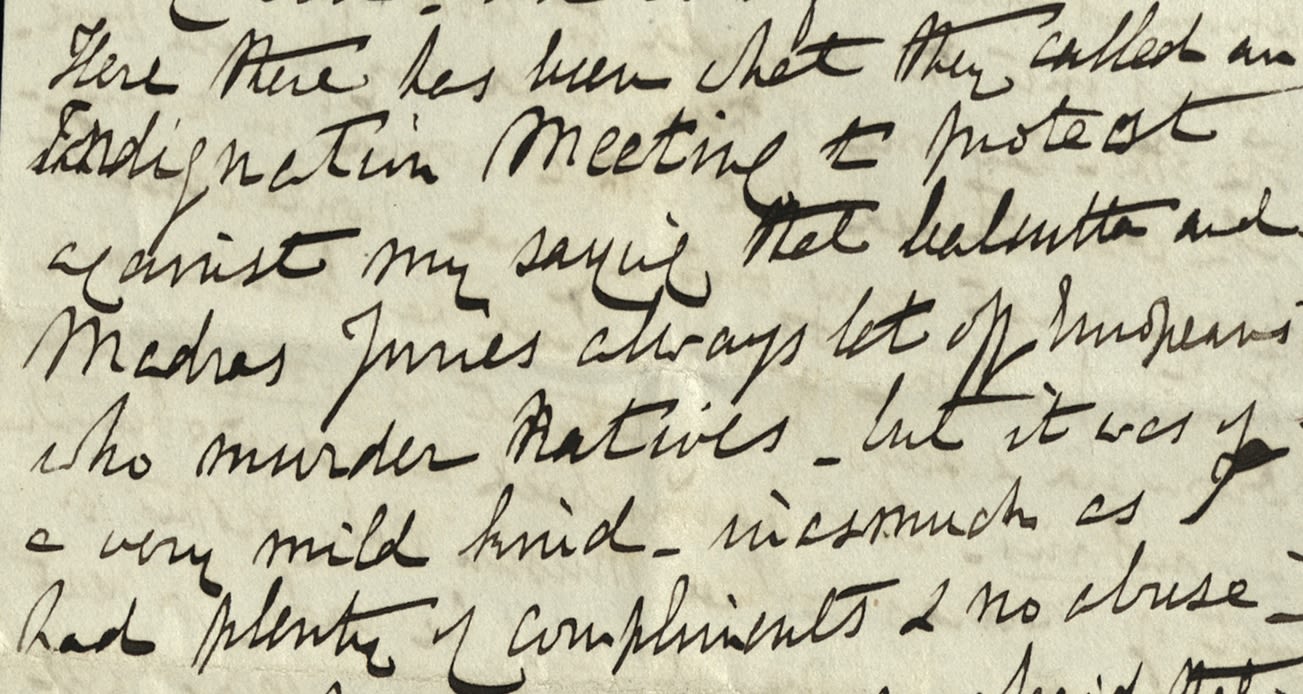

From his arrival in Chennai, Sir Charles's letters home were filled with his annoyance at the biased treatment of Europeans in the Madras courts . He didn't keep his dissatisfaction private.

"Here there has been what they call an Indignation Meeting to protest against my saying that Calcutta and Madras Juries always let off Europeans who murder Natives"

Background image: Newspaper clipping from the Sir Charles Edward Trevelyan Archive (CET/2/28/9)

Conclusions

The letters and documents included in this exhibition cover one of the most important eras in Indian and British history. Though written for the eyes only of his wife, Sir Charles's letters have provided an opportunity to show insights into the lives of the people who inhabited Chennai at this time.

Many more voices remain undiscovered within the pages of letters, diaries and journals, waiting to be shared.

The following video by Historian Sriram V. describes some of Sir Charles Edward Trevelyan's activity and legacy in Chennai.

Background image: Date Palms in the People's Park, Madras 1907, from a Tucks oilette postcard (tuckDB.org item 7065)

Find out more:

To learn more about the social history of Chennai, Sriram V. has produced a playlist of videos.

To view more images from the Trevelyan (Sir Charles Edward) Archive, please visit CollectionsCaptured.

This virtual exhibition was brought to you by Newcastle University Library Special Collections & Archives. With thanks to volunteer Charlotte Hawley and Historian Sriram V.